BACKGROUND ON OREGON’S STATEWIDE LAND USE PLANNING PROGRAM

CMP Direct Threats 1, 2, 3, 4

Prior to the 1960s, population growth was not broadly perceived as a concern in Oregon. Between 1940 and 1970, however, Oregon’s population grew by 109 percent. Subdivisions sprouted next to farms in the Willamette Valley and Oregonians saw their pastoral landscape threatened by sprawl. Governor Tom McCall and farmer-turned-senator Hector MacPherson collaborated on Senate Bill 100 (SB 100), which created Oregon’s land use planning program in 1973. In May 2023, Oregon celebrated 50 years of the land use program, which highlighted that proactive land use planning can provide more certainty to landowners and developers and can strategically protect natural resources and working lands.

The Statewide Land Use Planning Program has been charged by the legislature to manage urban growth and protect natural and working lands, including coastal, estuarine, and ocean resources. The Oregon Department of Land Conservation and Development (DLCD) is the state agency responsible for administering the statewide land use planning program, as well as ensuring local governments carry out the intent of the land use program in local planning and permitting. DLCD is guided by the Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC). While LCDC and DLCD have the statutory and administrative authority regarding the planning program, the program was established to preserve the principle of local responsibility or control of land-use decisions.

Oregon’s land use program is a partnership between local governments and state agencies, and local governments retain significant discretion as to how they implement the program through local comprehensive plans and implementation of land use ordinances. If local governments do not consider fish and wildlife habitat in local land use decisions, these resources will go unprotected, especially for those habitats that are not overseen by state agencies or other land use review processes. For example, the Oregon Department of State Lands regulates wetlands and waterways, but they do not regulate the riparian buffers; those are regulated by local governments through one of the Statewide Planning Goals.

Oregon’s Statewide Planning Program and 19 Statewide Planning Goals detail the state’s policies on land use and related topics, such as citizen involvement, urbanization, housing, working lands, and natural resources. Most goals are accompanied by guidelines, which are suggestions about how a goal may be applied, although guidelines are not mandatory.

One of the program’s 19 goals is Statewide Planning Goal 5. Unlike some of the more prescriptive goals, Goal 5 is more of a process goal, requiring decisionmakers to consider resource values rather than mandating their protection. When Oregon’s Statewide Land Use Planning Program was created, Goal 5 required local governments to adopt programs to protect natural resources, and conserve scenic, historic, and open space resources. This includes minerals and aggregates, historic and cultural resources, scenic waterways, open space, natural areas, energy resources, groundwater, wetlands, fish and wildlife habitat, and riparian corridors. The Goal 5 administrative rule also requires that local governments within a Metropolitan Service District (Metro) identify regional resources within Metro area cities and counties. For example, Portland Metro adopted Title 13 (Nature in Neighborhoods) of the Urban Growth Management Functional plan, which was acknowledged by DLCD as complying with Goals 5 and 6. Title 13 established requirements to protect, restore and conserve Metro’s significant riparian corridors and wildlife habitat resources.

There are six Goal 5 resource categories, and each category has separate state rules. Other than the DLCD Goal 5 rule for Greater Sage-Grouse, which defines significant sage-grouse habitat and directs counties to review applications for development permits using avoidance and mitigation criteria identified by ODFW, local governments make the determination on what fish and wildlife habitat resources they want to identify as significant to protect through their Goal 5 program.

The intent of the planning program and Goal 5 was that local governments would periodically review their comprehensive plans and inventories to adapt to changes. Goal 5 was meant to be proactive, wherein the best available data on habitat resources would be evaluated during 5-year reviews. However, in 2007, the legislature enacted a bill that revised the scope of periodic review to include only those cities with a population greater than 10,000. This means the focus of long-range planning is weighted toward meeting development objectives, rather than conservation goals. As a result, most fish and wildlife habitat protected through Goal 5 has not been updated since the 1980s, and local decisions are not incorporating the best available data for fish and wildlife resources. For example, oak habitats in the Willamette Valley often get converted as a result of rural residential development or wineries because this Key Habitat is not part of a local government’s Goal 5 program. Developing and maintaining close partnerships with local government and encouraging Goal 5 inventory updates will be crucial to ensuring that impacts to fish and wildlife habitat related to land development actions will be considered for future land use planning.

The Statewide Planning Goals includes four coastal goals, Goals 16-19, which provide a foundation for planning efforts that consider the impacts of development actions, as well as the uncertainties with climate change, on fish and wildlife resources in estuaries, shorelands, and beaches and dunes. In Oregon’s coastal zone, DLCD administers the Oregon Coastal Management Program for the National Coastal Zone Management Act (CZMA). As part of this program, DLCD determines federal consistency to ensure that land use decisions are consistent with the relevant agencies and the CZMA. This includes compatibility with local land use plans, state agency policies (e.g. fish passage, mitigation policies), comprehensive plans, and statewide planning goals.

Goal 16 addresses estuarine resources, and requires individual estuary plans to designate appropriate uses for different areas within each estuary, and to provide for review of proposed estuarine alterations to assure that they are consistent with overall management objectives and that adverse impacts are minimized. Goal 17 is related to coastal shorelands, such as marshes, and emphasizes the management of shoreland areas and resources in a manner that is compatible with the characteristics of the adjacent coastal waters. Goal 18 sets standards for development on beaches and dunes (e.g., dune grading, shoreline armoring), which helps to minimize impacts to Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN), such as Western Snowy Plover, and Coastal Dunes, a Key Habitat. Goal 19 is specific to open ocean resources and includes state agency interests, such as implementation of the Territorial Sea Plan. For more information on the governance of Oregon’s nearshore marine environment see Appendix – Nearshore Management Framework.

The program’s goals also include working lands, which represent a significant portion of Oregon’s land and income base. Oregon’s planning program protects working lands through Goals 3 and 4, which include zoning protections for agricultural and forestlands. Statewide Planning Goal 3 is for the preservation and maintenance of agricultural lands for farm use. Statewide Planning Goal 4 protects working forest land around the state, preserving it for commercial forestry while specifically recognizing its value for fish and wildlife habitat, recreation, and protection of air and water quality. These goals protect working landscapes, and by doing so, create benefits to fish and wildlife habitat, recreational opportunities, and protection of scenic landscapes. The Oregon Department of Forestry also tracks land use change on working forestlands in their Forests, Farms and People Report, which acknowledges the benefits of protecting working lands through the land use program. DLCD’s 2022-2023 Oregon Farm and Forest Land Use Report specifically highlighted the co-benefits of protecting working lands for conservation of wildlife habitat using ODFW’s Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas. This report also acknowledged that changes to the Goal 3 and 4 programs over the past 50 years, such as adding new uses or allowing substandard partitions for certain uses, have not necessarily considered erosion of the co-benefits the programs have for the conservation of Goal 5 habitat values. The 2023-2031 DLCD Strategic Plan includes a focus on conserving Oregon’s natural and working lands, with an objective to improve natural resource protection and climate resiliency.

Smart and sustainable planning is necessary to maintain a healthy environment, maintain habitat connectivity, adapt to climate change, and provide livable communities. A 2019 Oregon Values and Beliefs survey found that Oregonians value nature and the outdoors, with an emphasis of the importance of accessing nature. Protection of resources that provide the livability and quality of life that Oregonians rate highly can be balanced with efficient urban and rural development through land use planning.

ANTHROPOGENIC LAND USE

People’s presence on the land alters the shape, appearance, and function of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, influencing fish and wildlife populations. According to the Portland State Population Research Center, an estimated 4.2 million people lived in Oregon in 2024, and the population will continue to grow. As demand increases for housing, energy, infrastructure, and recreation, both urban and rural landscapes face mounting pressure. These land use changes result in significant and often permanent impacts to fish and wildlife habitat. This includes both direct and indirect anthropogenic impacts, at an individual or cumulative scale, which can significantly impact movements, habitat use patterns, and ultimately survival, with reproduction and overall population performance declines. Examples of anthropogenic impacts include:

Direct Habitat Loss and Fragmentation:

- Permanent Habitat Loss: Land use conversion of Key Habitats often results in complete and irreversible loss of habitat function and value. Mitigation may be recommended to offset or replace those losses. Restoration to a natural state is rarely feasible once areas are urbanized. Species may lose access to habitats necessary for critical life-history needs, such as breeding, migration, or overwintering.

- Habitat Fragmentation: Development disrupts habitat connectivity, impacting wildlife movement, migration routes, and access to seasonal ranges, which threatens long-term species viability. Infrastructure like roads and fences can act as barriers to terrestrial species, while culverts and dams can restrict aquatic species from reaching essential spawning habitats. Roads and railroads introduce mortality risks through vehicle collisions and can further isolate populations.

Indirect Habitat Impacts:

- Disturbance from Human Activity: Noise, artificial light, and presence of humans and domestic animals can disrupt wildlife behaviors, such as breeding, foraging, and migration, especially for amphibians, birds, and bats.

- Reduced Fitness and Displacement: Fish and wildlife may be displaced from high-quality habitats into areas with inadequate forage or cover or increased threats, which may lower survival and reproductive rates.

Direct Species Impacts:

- Threatened or Endangered Plants: Oregon’s threatened and endangered (listed) plants are legally protected on non-federal public land and regulation requires pre-project consultation with the Oregon Department of Agriculture Native Plant Conservation Program to help ensure actions on non-federal public land do not accidentally impact Oregon’s listed plants (OAR 603-073). A botanical survey, spatial analysis, or consultation completed before land actions commence is required to determine whether proposed projects are likely to impact listed plants.

Water Quality and Aquatic Habitat Degradation:

- Stream, Wetland, Floodplain, and Riparian Habitat Alteration: Development along streams can degrade or remove riparian buffers important for fish and wildlife, increase water temperature, and reduce off-channel habitat. Reduced water quality can lead to algal blooms and reduced oxygen levels, which are lethal for many aquatic species.

- Impervious Surfaces: Conversion of habitat to urban and rural uses can increase the extent of impervious surfaces, such as paved streets and parking lots, which alter hydrology, degrade water quality through runoff, reduce vegetation cover and diversity, and spread invasive species.

Disruption of Natural Disturbance Regimes:

- Natural Fire and Hydrological Regimes: Land use changes interfere with natural fire regimes and hydrological flows, affecting ecosystem function and resiliency. Many ecosystems depend on these natural regimes, and without them, habitat quality may decline, and invasive species may dominate.

Private Lands

Private and public lands play a critical role in providing Key Habitat for Species of Greatest Conservation Need. While 50% of the land in Oregon is in public ownership, many of the most critical fish and wildlife habitats are found on private lands. Even small development actions can result in cumulative landscape level impacts leading to significant population level effects for some species. Therefore, partnerships with private landowners, state and federal land management agencies, and tribal partners are critical to collaborate on measures to protect and manage sensitive life-history needs. These activities include habitat protection, managing recreational opportunities and other public land management, and the challenges that arise from increased development pressures.

Outdoor Recreation

With the growing human population in Oregon comes additional pressure on land managers to increase access to outdoor recreation opportunities such as hiking, mountain biking, and operating off-highway vehicles (OHV). Recreational pressure can lead to an increase in wildlife stress response and behavioral changes that ultimately impact reproductive rates and population abundance. Human recreation may contribute to destruction of sensitive vegetation, harassment of wildlife from off-leash pets, spread of invasive species, and contamination of areas with refuse. Many species will avoid areas near trails, campgrounds, and access roads when humans are present. Impacts of recreational activities to SGCN and Key Habitat function need to be considered in future planning processes. There is an opportunity for land managers and decision-makers to not just slow the loss of habitat but to actively contribute to maintaining and restoring wildlife habitat function while managing community values and priorities. Protection of fish and wildlife habitats and maintaining outdoor recreation opportunities for residents and visitors have both economic and nonmarket benefits.

Urbanization And Infrastructure

Goal 9 requires that all local governments have enough land available to realize economic growth and development opportunities, which includes commercial and industrial development-ready lands. Goal 14 establishes urban growth boundaries (UGBs) around each city or metropolitan area to separate urban land uses from farm and forest working lands. By concentrating urban development and associated impacts, the land use program has been reasonably successful in containing sprawl. In 2023, the Oregon legislature passed House Bill 2001, which directs the LCDC to adopt and amend rules related to housing and urbanization, related to Statewide Planning Goals 10 and 14. It requires Oregon’s cities with a population over 10,000 to plan for and encourage housing production, affordability, and choice through a Housing Capacity Analysis and a Housing Production Strategy. In 2023, Governor Tina Kotek also established a Housing Production Advisory Council (HPAC) through Executive Order 23-04, which established an annual housing production goal of 36,000 additional housing units at all levels of affordability across the state to address Oregon’s current housing shortage and keep pace with projected population growth. That represents an 80 percent increase over recent construction trends and should result in the construction of 360,000 additional homes by 2035.

Meeting these housing needs will require cities to implement strategies that consider how development projects may be affected by risk of natural hazards (e.g., floods, landslides, wildfires), and how to successfully facilitate housing production while minimizing impacts on water supplies. The Integrated Water Resources Strategy includes recommendations for improving the integration of water quality and quantity information into land use planning and encouragement of low impact development practices and green infrastructure to minimize impacts. This includes the protection of groundwater aquifers and wetlands, which support fish and wildlife habitat, as well as recommendations to update land use protections for riparian areas and wetlands through Statewide Planning Goal 5.

Most housing development takes place within urban growth boundaries and natural resources within urban areas provide essential functions and values to local communities and contribute to watershed health for fish and wildlife species. Wetlands and riparian habitat within urban areas provide essential corridors for animal movement, many that are identified as Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas (PWCA) or Conservation Opportunity Areas. The Oregon Department of State Lands works with local governments on integrating these aquatic resources into land use planning efforts, as well as with development projects to avoid, minimize and mitigate aquatic impacts through implementation of the Oregon Removal-Fill Law. For example, DSL may incorporate best management practices for native turtles, such as the Northwestern pond turtle, in wetland development projects, the ODFW Residential Dock Guidelines, and the Oregon Guidelines for Timing of In-Water Work to Protect Fish and Wildlife for overwater structures.

Protection of fish and wildlife habitat, such as maintaining tree canopies within urban areas, also helps to buffer impacts from climate change. As cities replace natural land cover with pavement, buildings, and other surfaces that absorb and retain heat, urban heat islands can occur. Due to climate change, extreme weather events such as extreme heat can increase in frequency and severity. Increasing tree canopy cover in an urban area not only reduces carbon dioxide but also helps address the urban heat island effect and improve air and water quality.

Rural Land Conversion

With increasing population and economic development, rural landscapes are changing, leading to conflicting uses within and adjacent to fish and wildlife habitat. For example, rural residential development for single-family homes, destination resort siting, and other large-scale developments such as mining operations and renewable energy facilities can result in direct habitat loss or cause species to change their distribution and habitat use patterns in response to disturbance. Impacts of development can go beyond the actual footprint of structures or roads. For example, increased water use or groundwater pumping within a development can reduce surface water quantity, impairing wildlife access to free water sources, which may lead to reduced ground water and soil moisture affecting vegetation growth patterns. Many local comprehensive plans acknowledge conflicting uses from rural developments and include habitat protections, such as housing density standards, siting standards (e.g., requiring wildlife friendly fencing), and clustering techniques to minimize habitat fragmentation.

Natural Resource Extraction

Natural resource extraction, such as mining for aggregate and critical minerals, also has direct and indirect impacts to fish and wildlife habitat. The Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries is the state agency responsible for working with permittees to coordinate mine permitting through all the required agencies to minimize impacts of natural resource extraction. Impacts to fish and wildlife habitats may include habitat conversion, habitat fragmentation from roads, direct habitat loss from mine development and extraction processes, and indirect impacts such as noise, disturbance and pollution from mining operations. Aggregate mining in the floodplain may remove riparian vegetation, alter stream channels, and entrap fish in the mining pits. Sagebrush habitat in southeastern Oregon has been targeted for mining exploration for critical minerals, such as lithium, and proposed mining for gold. Mining in Sagebrush habitat may affect a variety of SGCN, including Greater Sage-Grouse, Burrowing Owls, and pygmy rabbits, which depend on intact sagebrush habitats to persist. Early coordination regarding the impacts to Key Habitats and SGCN during the exploration phase and throughout the project development process is important to ensure that potential impacts are accurately identified, avoided, and minimized to the degree possible through best management practices, and mitigated where impacts remain after avoidance and minimization measures have been implemented.

Renewable Energy

Oregon has set aggressive goals for decarbonizing the state’s energy system, with an objective of 100% renewable energy by 2040. This timeline has created a high interest in the development of new solar and wind energy facilities within the state. As more energy projects are established on Oregon’s landscape, there will be cumulative impacts to the availability, quality, and accessibility of viable habitat. In addition, the regional demand for a cleaner energy system and increased power needs for emerging technologies will continue to drive renewable energy development. The primary renewable energy developments are photovoltaic solar and wind energy. Each of these development types can have differing direct and indirect impacts on the landscape. Direct impacts include habitat loss from the development footprint or exclusion by project fencing. Indirect impacts include increased disturbance during construction and maintenance activities within facilities, habitat fragmentation from roads and fences associated with project development, and wildlife avoidance of project areas. Wind development projects generally have lower amounts of total disturbed habitat than solar facilities, but the footprint is distributed over a greater number of acres. Potential impacts from wind facilities are assessed using the US Fish and Wildlife Service Wind Energy Guidelines, providing a consistent approach nationwide to assessing direct mortalities and displacement generally associated with wind development.

The Columbia Plateau ecoregion has seen considerable wind and solar energy development over the past two decades, given its resource potential and proximity to transmission infrastructure. Other portions of eastern Oregon have seen solar development proposals, with the highest solar irradiance in the state found in the East Cascades, south of Bend, and the Northern Basin and Range. Other potential energy generation technologies being explored in Oregon include geothermal, offshore wind, and wave energy. The existing electric transmission system will also need to be upgraded to maintain reliable service, meet new demand, and connect renewable energy development to electric loads. Additional infrastructure associated with energy, including access roads and pipelines, can also impact the landscape.

DLCD has developed administrative rules for wind and solar energy siting on agricultural land based on input from energy providers and conservation groups. DLCD rules provide guidance and direction regarding local land use decisions for solar and wind facilities, and policies for siting ocean energy facilities. However, the Oregon Energy Facility Siting Council or the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission make the siting decisions for large energy facilities and transmission infrastructure. Regardless of the regulatory pathway, engagement by state, federal, tribal, and conservation partners is key to balancing energy development with impacts to fish and wildlife and their habitats.

In 2019, the Oregon Department of Energy (ODOE) partnered with DLCD and the Oregon Institute for Natural Resources (INR) on a grant application to the U.S. Department of Defense for the study and assessment of renewable energy and transmission development in Oregon. The Oregon Renewable Energy Siting Assessment (ORESA) is an online mapping and data portal that includes consideration of important fish and wildlife habitat for proactive energy siting.

The effects of climate change on Oregon’s habitats and species are becoming more evident, and state policies are becoming more ambitious in identifying potential pathways to reduce or slow the rate of change realized. Current state goals for removing carbon from Oregon’s energy portfolio are diverse but will require siting for new renewable energy projects in the state. Energy projects offer environmental benefits but also have impacts on fish, wildlife, and habitats. So far, energy policy has focused on the broad need to reduce emissions (e.g., Northwest Power Planning Council), but typically does not address local or site-level impacts. At the same time, site evaluations for specific projects typically focus on the immediate and local effects of a project, without consideration of its broader benefits. Climate change and the increasing call for clean energy challenge agencies and partners to work together in seeking creative ways to bridge the gap. Future policies to guide new clean energy development should outline a collaborative vision for energy siting practices, and, while recognizing the immediate but dispersed value of clean energy across Northwest landscapes, should incorporate fish, wildlife, and habitat values.

LAND USE PLANNING: GOALS AND ACTIONS

Goal 1: Manage land use changes to protect and conserve farm, forest, and range lands, open spaces, natural or scenic recreation areas, and fish and wildlife habitats.

Action 1.1. Encourage the updates of local land use plans and ordinances that protect Key Habitats to support fish and wildlife.

Many important decisions about land use occur at the local level through comprehensive land use plans. These plans consider local values, priorities, and needs. Agencies will need to work with local community leaders and other stakeholder groups to find opportunities to incorporate SGCN, Key Habitats, Conservation Opportunity Areas, Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas, and other priorities into local plans that conserve farmlands, forestlands, open space, and natural areas. This should include working with DLCD and local governments to adopt land use ordinances that incorporate measures into land use reviews and decisions that avoid, minimize or mitigate conflicting uses to fish and wildlife habitat. Promote ordinances that minimize habitat fragmentation, establish riparian buffers to protect water quality and temperature, require wildlife friendly fencing, include timing and seasonal restrictions to minimize disturbance during sensitive life history stages, and require mitigation for unavoidable impacts. The opportunity to re-establish periodic reviews for fish and wildlife data to ensure incorporation of newly acquired information needed to inform land use management decisions should also be explored. The Integrated Water Resources Strategy also includes recommendations for water planning, which includes integrating water data and information in land use planning that can support habitat functions for fish and wildlife.

Technical assistance, such as outreach and education, will be necessary to support local governments and stakeholders to integrate current data. Support and partnerships are necessary, which may involve the creation of toolkits, guidance, and training for integrating habitat conservation into development planning and permitting. For example, Oregon would benefit from development of a Green Growth Toolkit to assist communities in implementing conservation actions and proactively planning for growth as development pressures increase. It is important to acknowledge the challenges that arise when trying to balance resource protection, economic development, and social considerations in development projects. However, it is possible to plan for contained, well-designed growth which can avoid and minimize impacts to surrounding landscapes and help conserve fish, wildlife, and habitat, as well as working lands.

Action 1.2. Encourage land use planning efforts to integrate opportunities for addressing climate change, such as climate-smart practices and nature-based solutions in development actions.

The Oregon Climate Adaptation Framework identifies the need to leverage the statewide land use planning program and develop land use planning guidance based on Oregon’s Statewide Land Use Planning Goals to help cities and counties incorporate climate science and engagement of diverse communities into their planning, permitting, and operations as an adaptation strategy. It also acknowledges the need to review the Planning Goals, as challenges related to climate change were not anticipated when the foundational program was established. This provides an opportunity to acknowledge and integrate the co-benefits of protecting and restoring riparian, floodplain, and wetland habitats as a climate adaptation strategy. Most comprehensive plans have identified natural resources through Statewide Planning Goal 5, as well as through Goal 16 for estuarine resources, but most do not adequately consider habitat functions or values, especially to address new environmental, social, and economic challenges associated with climate change. Habitat protection and restoration as a climate adaptation strategy may also be achieved through natural hazard planning. Integrating nature-based solutions through planning (e.g., incentives, ordinances), design, and engineering practices can address natural hazards (e.g., erosion, landslide risk, wildfire risk, flood storage, water quality), protect and enhance fish and wildlife habitat, and enhance community resilience. The Integrated Water Resources Strategy also acknowledges the challenges from land use and climate change and recommends actions to protect and restore green infrastructure. This includes protection of wetlands, floodplains, and forests, which can help to address climate mitigation and adaptation. DLCD is also addressing mitigation and adaptation of climate change related to land use and transportation, natural hazard planning, and coastal management. Numerous resource management agencies have also implemented climate policies that can help guide planning and development across the state. For example, ODFW adopted a Climate and Ocean Change Policy in 2020 that can support the incorporation of impacts from climate and ocean change on fish, wildlife and their habitats into planning efforts.

Many local governments in Oregon have already or are in the process of developing climate action plans for their communities, and some local governments are considering updates to their estuary management plans. These community-driven efforts usually include scenario planning and conducting a vulnerability analysis for the environmental, economic, and societal impacts from climate change. Opportunities to incorporate tools, such as Conservation Opportunity Areas and Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas, may be useful in identifying climate focal areas to protect and restore floodplain and riparian habitat as a strategy to comply with the floodplain requirements and meet greenhouse gas metrics through carbon storage (e.g., blue carbon) and carbon sequestration. Prioritizing habitat through actions such as nature-based solutions can optimize societal and ecological benefits by reducing exposure to climate hazards, reducing sensitivity to adverse effects, and building adaptive capacity of local communities. There are also opportunities to integrate low impact development and green infrastructure to increase climate resiliency as Oregon experiences increased temperatures, drought, and flooding.

Action 1.3. Encourage strategic land conservation and restoration to protect Key Habitats using a suite of tools, such as financial incentives, conservation easements, landowner agreements, mitigation, and targeted acquisitions.

A range of incentives and conservation tools will complement landowner’s unique circumstances and priorities. Outreach to partners, including land managers and local governments, can provide information about incentives to conserve SGCN, Key Habitats, PWCAs, and Conservation Opportunity Areas. The SWAP Conservation Toolbox provides a summary of voluntary, non-regulatory approaches to conserving fish and wildlife and recommendations to further assist willing landowners to protect and restore Key Habitats.

It is also important to promote partnership opportunities for protection of natural and working lands. This may include opportunities for working lands conservation easements, such as through the Natural Resource Conservation Service Agricultural Conservation Easement Program or local land trusts. There are also many existing incentive programs to conserve natural and working lands, such as ODFW’s Wildlife Habitat Conservation and Management Program. The Oregon Wetland Program Plan includes a Core Element of “voluntary wetland restoration and protection”, with a focus on restoration and protection, including actions for continuing stream and wetland restoration, and working with counties to enroll properties in the ODFW tax incentive programs. Other programs through the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, such as the Oregon Agricultural Heritage Program funds voluntary incentives to support practices that maintain or enhance both agriculture and natural resources such as fish and wildlife habitat on agricultural lands.

In many land use permitting processes, ODFW may recommend mitigation to offset unavoidable impacts to fish and wildlife habitat. Identification of places with broad conservation opportunities can direct potential mitigation projects to strategic areas with the highest ecological value.

Goal 2: Work proactively and collaboratively to encourage land development actions that are well-sited, adequately mitigated, and responsibly operated to conserve Species of Greatest Conservation Need and Key Habitats.

Action 2.1. Increase access to and use of the best available data and maps to plan for and site land development that avoids or minimizes impacts on fish, wildlife, and their habitats.

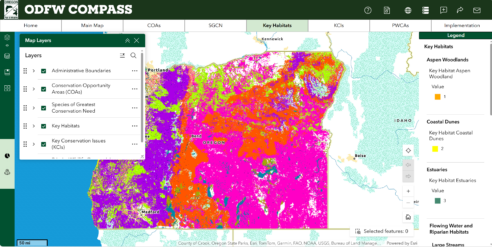

As Oregon continues to plan for future growth, the Statewide Land Use Planning Program and Planning Goals should still be the foundation. Local governments, state agencies, conservation organizations, private industry, tribes, and the general public need access to the best available data for land use decisions to avoid and minimize impacts. Spatial information on Species of Greatest Conservation Need, Key Habitats, Conservation Opportunity Areas, Oregon Fish Habitat Distribution and Barriers Data, PWCAs, and other mapped information for Oregon is available using the ODFW Compass mapping application. Information, data, Traditional Ecological Knowledge, and analyses on fish and wildlife habitat function should continue to be shared for integrating into development planning and projects.

Agencies such as DEQ and DSL also have designations for protecting Key Habitats. For example, DEQ designates cold water habitat, and DSL designates and protects Aquatic Resources of Special Concern, which include many Key Habitats (e.g., wet prairie, vernal pools, interdunal wetlands) that are either naturally rare or have been disproportionately lost due to prior impacts.

Oregon is currently facing siting needs related to renewable energy goals established for the state. These needs can be met by using the best available information, with additional technical assistance and local data from Oregon’s natural resource agencies. Agencies and partners can work to provide the tools, scientific knowledge, and assistance to support consistent, defensible, and predictable siting decisions and operational requirements. The Oregon Department of Energy hosts the Oregon Renewable Energy Siting Assessment tool (ORESA) that was developed specifically to serve as a central clearinghouse for data from multiple organizations, and serves as a decision support tool for all entities engaged in energy siting. Available guidance documents include the ODFW Solar Siting Guidance (2024), Oregon Columbia Plateau Ecoregion Wind Energy Siting and Permitting Guidelines (2008) and the USFWS Land-Based Wind Energy Development Guidelines (2012). In addition, the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies hosts resources from across the nation, many of which can inform issues that may be new to Oregon.

To further enhance the availability and use of the best available information, natural resource agencies should develop clear and comprehensive mitigation strategies and siting guidance for all types of energy development. For renewable energy projects, avoiding or minimizing impacts on fish, wildlife, and their habitats means working with utilities companies and planners to co-locate transmission within existing infrastructure to help offset potential impacts from development. This may also include prioritizing previously disturbed sites, or sites that avoid Key Habitats and Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas. For management of recreational uses, this may include co-locating any new trails, roads, or other needed amenities in areas that are already disturbed and experience a high level of impact.

Action 2.2. Encourage engagement in regional, statewide, and federal planning priorities, such as those related to energy and housing, to promote collaborative solutions and strategies that incorporate consideration of Key Habitats and Species of Greatest Conservation Need, including the consideration of cumulative impacts.

Proactive engagement with land use managers and planners, agencies, and project developers as Oregon continues to experience land use pressures is essential to ensure that the best available data for fish and wildlife are being considered. This includes seeking collaborative solutions and the development of shared goals, priorities, and strategies. There are multiple statewide plans that prioritize goals for Oregon that reference the land use planning program, but better alignment of shared interagency priorities is needed. This could include strategic mapping efforts, such as the prioritization of protection of natural and working lands, that provide co-benefits to fish and wildlife habitat. Opportunities for providing technical assistance and outreach to stakeholders is also critical for collaboration and engagement.

Additional coordination across stakeholders is also needed to evaluate and monitor the impacts of large-scale development projects on species and habitats. This includes a better understanding on how large-scale developments affect wildlife habitat use and movement, population level impacts, and cumulative habitat loss. Partnerships will be critical to implement this need.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Oregon Integrated Water Resources Strategy (2025)

ODFW Climate and Ocean Change Policy

Oregon Guidelines for Timing of In-Water Work to Protect Fish and Wildlife Resources (2024)

ODFW Residential Dock Guidelines (2016)

Oregon Climate Action Commission and Natural and Working Lands Report

1000 Friends of Oregon: Death by 1000 Cuts (2020)

Defenders of Wildlife: Making Renewable Energy Wildlife Friendly

Lincoln Institute of Policy and Planning: Integrating Land Use and Water Management

The Big Look (2009): The Oregon Task Force on Land Use Planning Final Report

The Oregon land use system: an assessment of selected goals INR Report (2008)

Energy Facility Siting Standards

Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies Energy and Wildlife Program

American Wind Wildlife Institute

Defenders of Wildlife Renewable Energy Program

National Energy Technology Laboratory Research

American Clean Power Association Resources

Columbia Plateau Wind Energy Siting Guidelines

USFWS Eagles in the Pacific Northwest: Energy, Utilities, & Guidance