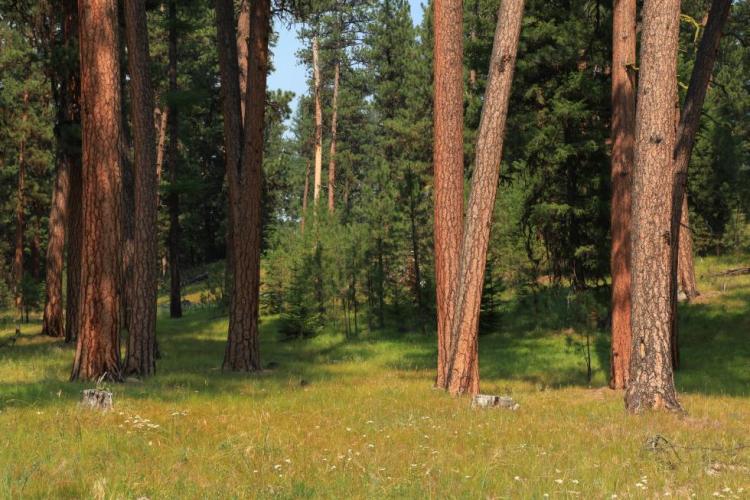

Ponderosa pine woodlands are common in Oregon’s eastside ecoregions. While dominated by ponderosa pine, these woodlands may also have lodgepole pine, western juniper, aspen, western larch, grand fir, Douglas-fir, mountain mahogany, incense cedar, sugar pine, or white fir, depending on ecoregion and site conditions. Known for their open forest structure, these woodlands generally have fewer than 40 large trees per acre, with tree canopy cover between 10 and 60%. Understories consist of variable combinations of fire tolerant shrubs, herbaceous plants, and grasses. Ponderosa pine forests generally occur in regions with arid conditions with little rainfall during summer months, and can be found at a range of elevations, from 100 ft to over 6000 ft.

Ecoregional Characteristics

Blue Mountains

In the Blue Mountains, ponderosa pine often coexists with other conifers, such as Douglas-fir, western larch, and grand fir. The understory is diverse, including shrubs like mountain big sagebrush, bitterbrush, mahogany, snowbrush and various native grasses and forbs such as Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass. Ponderosa pine habitats also include savannas, which have sporadic, widely spaced trees that are generally more than 150 years old. The structure of a savanna is open with an understory dominated by fire-adapted grasses and forbs as well as shrub fields. Ponderosa pine habitats in the Blue Mountains generally occur at mid elevation and are replaced by other coniferous forests at higher elevations.

East Cascades

East of the foothills of the Cascades, within the rain shadow cast by the mountains, land becomes more arid and ponderosa pine woodlands become dominant. In these woodlands, other conifer species may be present, including Douglas-fir, western larch, and, in some areas, lodgepole pine. The understory is characterized by a mix of shrubs and herbaceous plants. Common shrubs include bitterbrush, mountain big sagebrush, and snowberry. The herbaceous layer often includes native grasses such as Idaho fescue and bluebunch wheatgrass. Ponderosa pine habitats in the East Cascades generally occur at mid elevation, where climatic and soil conditions support the growth of these trees, and are replaced by other coniferous forests at higher elevations.

Klamath Mountains

In the Klamath Mountains, pine woodlands are usually dominated by ponderosa pine, but may be dominated by Jeffery pine, depending on soil mineral content, fertility, and temperatures. Ponderosa pine and ponderosa pine-oak woodlands occur on dry, warm sites in the valley margins, foothills, and mountains of southern Oregon. The understory often has shrubs, including green-leaf manzanita, buckbrush, and snowberry.

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor: Altered Fire Regimes and Addressing Risk of Uncharacteristically Severe Wildfire

Certain timber harvest practices, the exclusion of Indigenous peoples’ burning practices, and fire suppression have resulted in dense growth of young pine trees and young mixed conifer stands, replacing the open understory of ponderosa pine woodlands. These dense stands are at increased risk of uncharacteristically severe wildfires, drought, disease, and damage by insects. Over time, some stands will convert to Douglas-fir and grand fir forests, which do not provide adequate wildlife habitat for species dependent on open ponderosa pine habitats. While normally drought tolerant, large old-growth ponderosa pines are competing for resources with these dense, young trees that would historically have been controlled by frequent, low intensity fires.

These crowded understories, along with numerous insect-killed trees, make it difficult to reintroduce natural fire regimes in some areas, particularly in the Blue Mountains and East Cascades ecoregions. In parts of the Blue Mountains, East Cascades, and Klamath Mountains, increasing development of homes and resorts in forested habitats limits the ability of managers to use prescribed fires due to concerns about smoke and escaped burns, further increasing the risk of high-intensity wildfires. Some ponderosa pine woodlands are also being inundated with invasive annual grasses such as cheatgrass and medusahead, increasing fuel continuity and altering natural fire behavior.

Recommended Approach

Use an integrated approach to forest health issues that considers historical conditions, including roads and human use, wildlife conservation, natural fire intervals, and silvicultural techniques. Develop implementation plans for thinning overstocked stands and applying prescribed fire, and ensure plans are acceptable for management of both game and non-game species. Evaluate individual stands to determine site-appropriate actions, such as monitoring in healthy stands, or thinning, mowing, and application of prescribed fire in at-risk stands. Develop markets for small-diameter trees and implement fuel reduction projects to reduce the risk of forest-destroying wildfires. Manage for a landscape mosaic that includes structural complexity and species diversity in the understory and overstory across multiple spatial scales. Fuel reduction strategies need to consider the habitat structures that are required by wildlife, including snags, downed logs, and hiding cover. Reintroduce fire where feasible. Engage with Tribal Nations to bring Traditional Ecological Knowledge of prescribed fire to the overstocked forests. Implement prescribed fire at a frequency and scale that improves regeneration and establishment of native shrubs

Support community-based forest collaboratives to increase the pace and scale of forest restoration. Engage in frequent outreach to educate the public about the ecological importance of fire to ponderosa pine forests. Monitor forest health initiatives and use adaptive management techniques to ensure efforts are meeting habitat restoration and uncharacteristic fire prevention objectives with minimal impacts on wildlife. Work with landowners and resort operators to reduce vulnerability of properties to wildfires while maintaining habitat quality. Highlight successful, environmentally sensitive fuel management programs. Retain features that are important to wildlife, including snags, downed logs, forage, and hiding cover for wildlife species, and replant with native shrub, grass, and forb species. Manage reforestation after wildfire to create species and structural diversity based on desired future condition and local management goals. (KCI: Disruption of Disturbance Regimes)

Limiting Factor: Loss of Size and Connectivity of Large-structure Ponderosa Pine Habitats

Old-growth ponderosa pine habitats have been greatly reduced in size and connectivity by timber harvest, the exclusion of Indigenous peoples’ burning practices, and fire suppression, particularly in the Blue Mountains and East Cascades ecoregions. These changes have led to overstocked stands. Alongside the loss of open understories and encroachment by dense stands of young trees, many ponderosa pine habitats have been lost to conversion to rural residential uses and other activities. As a result, few large, contiguous blocks of ponderosa pine habitat remain.

Recommended Approach

Maintain large blocks of large-diameter ponderosa pine habitat. Identify current and potential movement corridors between habitat blocks for protection and restoration. In areas experiencing rapid development, work with local communities to minimize development in large blocks of intact habitat.

Limiting Factor: Invasive Species

Throughout the state, non-native plants are invading and degrading ponderosa pine woodlands. In parts of the Blue Mountains and East Cascades, diffuse and spotted knapweed and Dalmatian and common toadflax are significant invaders. Additionally, in many areas the spread of cheatgrass and medusahead rye can result in an invasive plant understory with a high-fuel content that is highly susceptible to burning and carries wildfire more easily than the native vegetation. In the Klamath Mountains, Armenian (Himalayan) blackberry and Scotch broom are significant invaders, along with annual invasive grasses.

Recommended Approach

Emphasize prevention, risk assessment, early detection, and quick control to prevent new invasive species from becoming fully established. Prioritize efforts and control key invasive species using site-appropriate methods. Control wildfires in cheatgrass-dominated areas of the Blue Mountains. In natural ponderosa pine habitats with few invasive species, promote early detection through monitoring and quickly control invasives at first detection, when control is more efficient, practical, and cost-effective. Reintroduce site-appropriate native grasses and forbs after invasive plant control. Prescribed burning may be useful for management of some invasive species in the Klamath Mountains.