Description

Oregon’s Nearshore ecoregion offers opportunities for boating, surfing, wildlife viewing, fishing, crabbing, clamming, and recreational pursuits. It supports commercial fish harvests and shipping that includes export of many products and commodities like wood produced in Oregon as well as imports of products from around the world. The Nearshore provides ecosystem services that benefit all Oregonians.

The nearshore environment includes a variety of habitats ranging from submerged high-relief rocky reefs to broad expanses of intertidal mudflats in estuaries. These habitats are described in more detail in the Nearshore and Estuaries Key Habitats. A vast array of fish, invertebrates, marine mammals, birds, algae, plants, and micro-organisms make their homes here. These habitats and species are integral parts of Oregon’s complex nearshore ecosystem, and are interconnected through food webs, nutrient cycling, habitat usage, and ocean currents. They are also influenced by a multitude of other biological, physical, chemical, geological, and human use factors.

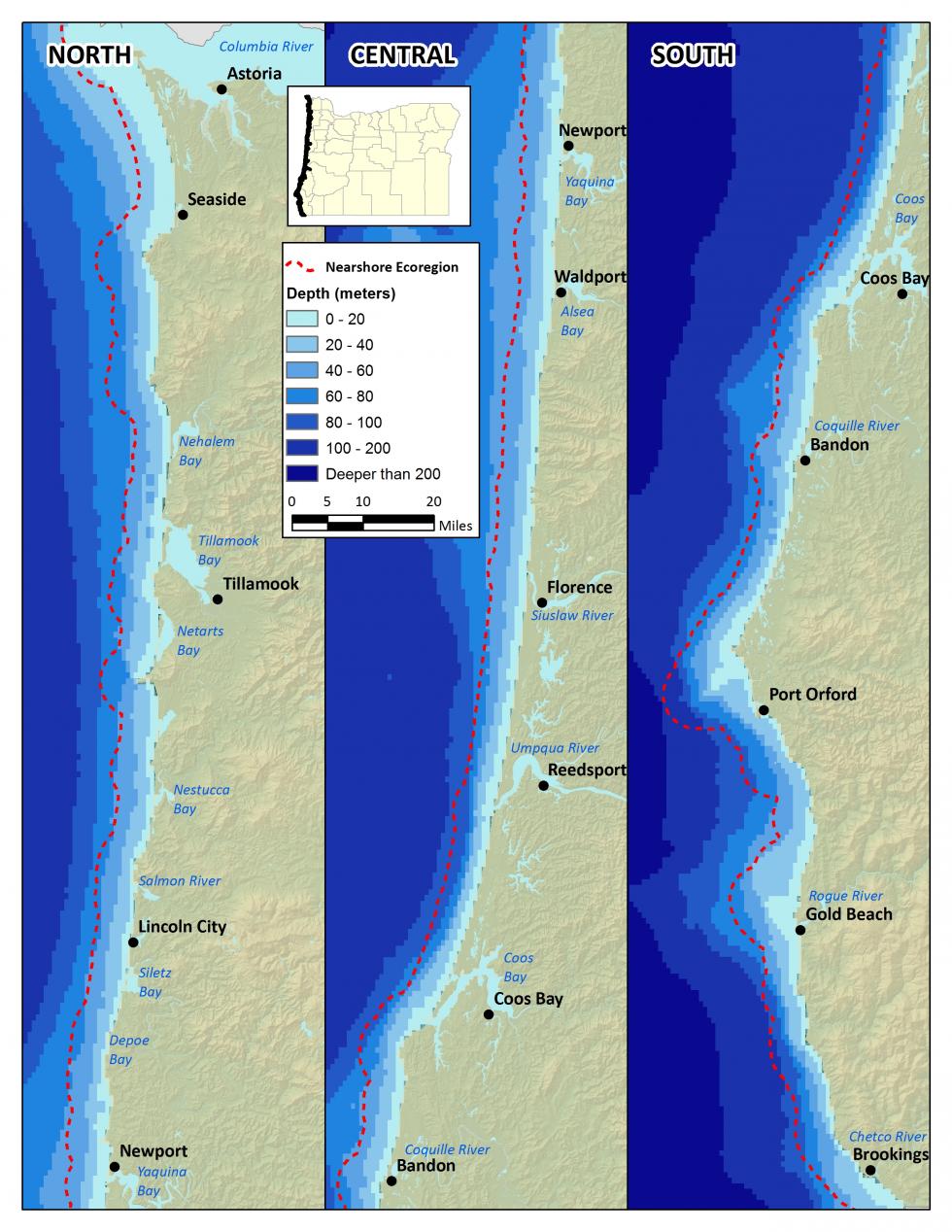

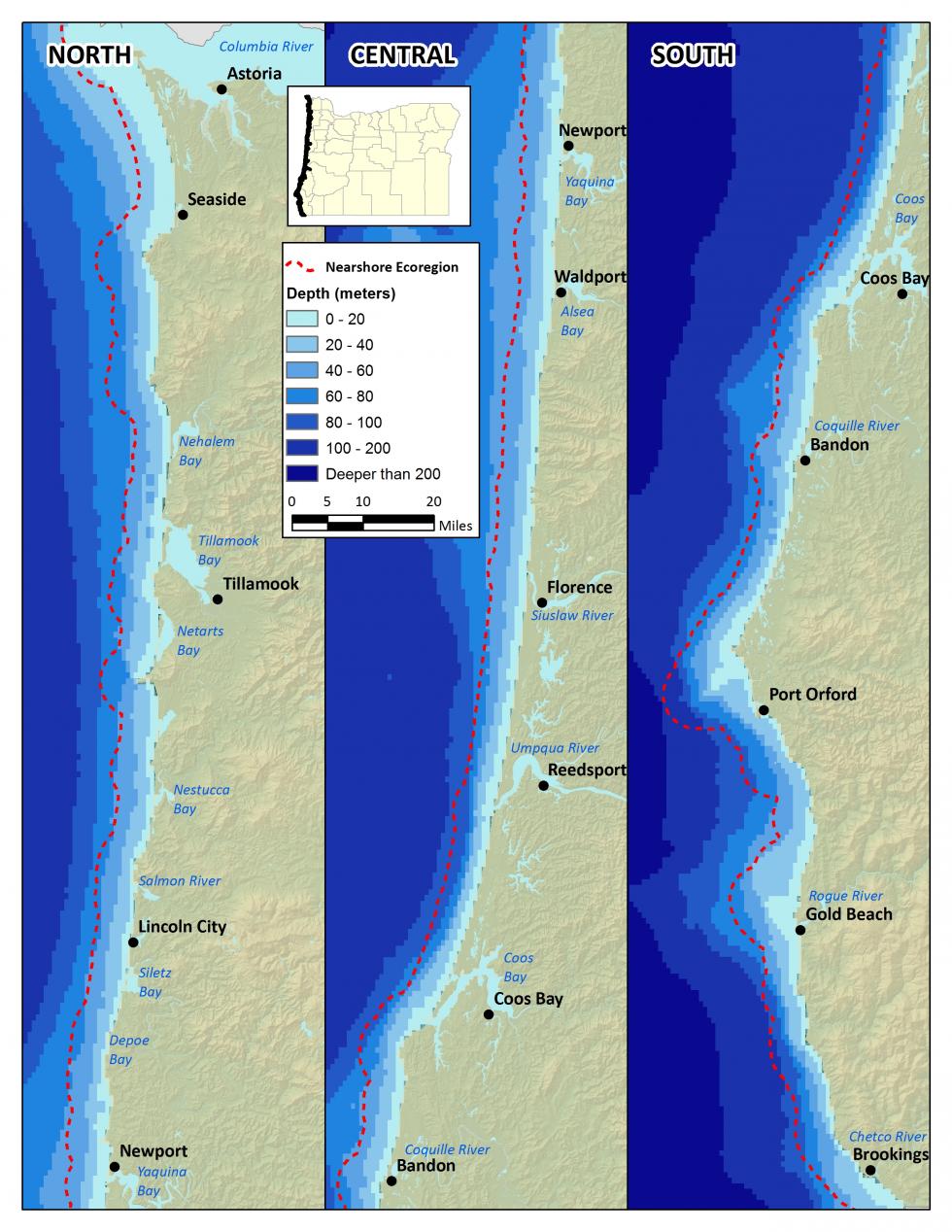

The Nearshore ecoregion encompasses the area from the outer boundary of Oregon’s Territorial Sea at 3 nautical miles to the supratidal zone affected by wave spray and overwash at extreme high tides on the ocean shoreline, and up into the portions of estuaries where species depend on the saltwater that comes in from the ocean. The Nearshore ecoregion is bordered by the Coast Range Ecoregion on the ocean shores and intersects it in Oregon’s estuaries where the influence of the terrestrial watersheds are strongest (Figure 1). Humans are an important part of the ecology of the Nearshore ecoregion and coastal communities are an integral part of that ecology (see Appendix – Coastal Communities).

Characteristics

Important Industries

The distinct suite of oceanographic features and physical forcing agents that help define the Nearshore ecoregion include the northern portion of the California Current System and the annual seasonal upwelling/downwelling cycle that are responsible for its high productivity (Figures 2 and 3). The eastern boundary current is a part of the North Pacific gyre that moves cold water from the North Pacific toward the equator. It has a southward flowing current over Oregon’s shelf and slope and a northward flowing undercurrent over the slope in spring and summer. In winter, the current over the shelf consists primarily of the northward flowing Davidson current (Figure 2).

During spring and summer, winds blowing from a northerly direction drive an upwelling system that brings cold, nutrient-rich, and oxygen-poor waters from depth up onto the continental shelf (Figure 3a). The upwelling process is highly variable on many time scales and is generally stronger and more persistent on the south Oregon coast and more intermittent on the central and northern Oregon coast. In addition to nutrients derived from upwelling, river discharge from the Columbia River provides a major source of nutrients to the Oregon continental shelf, especially along the north coast. The upwelling and river-plume nutrients fuel high phytoplankton productivity which drives an extremely productive marine ecosystem off Oregon. In the fall and winter months winds blowing from a southerly direction cause seasonal downwelling that bring well oxygenated water from the surface downward in the water column (Figure 3b). Surface water temperatures provide a good indication of these seasonal wind forcing differences that bring the cold, nutrient-rich waters to the surface in the summer (Figure 4a) and the warmer waters from offshore to the coast in the winter (Figure 4b). Superimposed on these large-scale processes are smaller scale eddies, gyres, fronts, and other oceanographic phenomena, which together serve to create a complex spatially and temporally dynamic ecosystem.

In 2012, the Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard (CMECS) was adopted in the United States (Federal Geographic Data Committee 2012) as a means to provide a common framework for describing habitat, using a simple, standardized classification scheme and common terminology. The goal of using CMECS is to both enhance scientific understanding and to advance ecosystem-based and place-based resource management through better communication. Components of the CMECS classification framework have been incorporated into the SWAP – in particular, the CMECS approach to evaluating and describing Nearshore Key Habitats. For more information on the CMECS Framework see Appendix – Marine Habitat Classification.

Major Crops

Commercial fishing, fish processing, tourism and recreation (including recreational fishing, shellfish harvest, and wildlife viewing), mariculture, and shipping.

Important Nature-based Recreational Areas

All open water, surf zone, subtidal rocky reefs, sandy beaches, rocky intertidal areas, and estuaries. Ecola Point Marine Conservation Area, Chapman Point Marine Garden, Haystack Rock Marine Gardens Cape Falcon Marine Reserve and West Marine Protected Area, Cape lookout Marine Conservation Area, Tillamook Bay, Netarts Bay, Cape Kiwanda Marine Garden, Fogarty Creek Marine Conservation Area, Boiler Bay Marine Research Area, Cascade Head Marine Reserve and its North, South and West Marine Protected Areas, Pirate Cove Marine Research Area, Whale Cove Marine Conservation Area, Otter Rock Marine Garden, Otter Rock Marine Reserve, Yaquina Head Marine Garden, Yaquina Bay, Yachats Marine Garden, Cape Perpetua Marine Garden, Neptune Marine Research Area, Cape Perpetua Marine Reserve and Marine Protected Areas, Coos Bay, Gregory Point Marine Research Area, Cape Arago Marine Research Area, Cape Blanco Marine Research Area, Redfish Rocks Marine Reserve and Protected Areas, Coquille Point Marine Garden, Harris Beach Marine Garden, Brookings Marine Research Area

Elevation

From approximately 10 feet above to 636 feet below sea level

Number of Vertebrate Wildlife Species

226

Important Rivers

Alsea Bay, Chetco River, Columbia River, Coos Bay, Coquille River, Depoe Bay, Elks River, Necanicum River, Nehalem Bay, Nestucca Bay, Netarts Bay, Pistol River, Rogue River, Salmon River, Sand Lake, Siletz Bay, Siuslaw River, Sixes River, Tillamook Bay, Umpqua River, Winchuck River, Yaquina Bay

Ecologically Outstanding Areas

Oceanographic influences: California current, seasonal upwelling

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor:

Public Awareness

Numerous marine species and habitats occur below the water’s surface and go unseen by most members of the public. Many people will not have the opportunity to go out on the ocean or even visit the coastline. Without firsthand experience, the effects that humans have on the nearshore ecosystem through pollution, climate change, invasive species and other Key Conservation Issues facing nearshore species and their habitats are poorly understood. Education and outreach efforts are needed to increase public awareness about nearshore marine species and habitats, as well as the issues affecting them.

Recommended Approach

Improve education and outreach efforts to disseminate information on species identification and distribution, management regulations, and release techniques designed to reduce discard mortality. Develop curriculum materials and provide information to schools for use in classrooms about the effects humans are having on the Nearshore ecoregion, the Nearshore species that live there, and conservation actions. Employ emerging technologies, blogs, and social media sites. Use local newspapers and literature to share research and conservation actions with adults and children. Display conservation and educational materials at hotels, charter offices, angling shops, real estate offices, malls, parks, marinas, boat ramps, beach access points, and other public areas. Encourage development of local and port groups to facilitate information and knowledge exchange between agencies and local constituents. Design and convene workshops tailored to educate the public on specific topics (e.g., fish, algae, shellfish, non-native species identification workshops).

Limiting Factor:

Habitat Alteration

CMP Direct Threats 1, 2.4, 3.3, 6.1, 6.2, 7.3, 8.1, 8.4, 9, 10.2, 11

Disturbance or loss of Nearshore Habitats important to nearshore species can result from both direct and indirect sources. Disturbances to vulnerable intertidal habitats are often subtle and can be a consequence of human activities that cause light or noise pollution or result in trampling of intertidal habitats, animals, or plants. Intertidal and submerged habitats are impacted by changes to sediment transport due to altered hydrology, coastal development, shoreline armoring, beach grooming, global climate change, and many other factors. Non-native species introductions may alter physical properties and habitat-forming biological communities (e.g., crowding out native organisms that function as substrate for other organisms). Certain bottom fishing methods may reduce structural diversity of the sea floor and change benthic communities. Development of renewable energy facilities such as wind and wave energy and their anchors and cables may alter habitats in a variety of ways such as altering winds and currents. Dredging, dredge and fill activities, shellfish mariculture, building dikes and levees, and installation and removal of tide gates are all examples of habitat alteration. Habitat in Estuaries has been transformed and altered by the introduction of the non-native species of Japanese eelgrass.

Recommended Approach

Continue to monitor species and habitats to document impacts that may be subtle or may accumulate over time, and to determine areas where disturbance is causing, or could cause, negative impacts to species or habitat. Collaborate with academic and management entities in the study of non-native species, survey intertidal and subtidal habitats for presence, set a baseline of habitat use, and monitor communities for potential spread. Investigate alternative methods (e.g., fishing techniques, shoreline erosion control, development practices) that reduce or remedy negative impacts on habitats. Inform the public about the use of non-disturbing methods appropriate for viewing marine wildlife. Provide new or improved interpretive signage, media inserts, feature articles and booklets about intertidal habitats, fisheries information, and other nearshore ocean resources. Examine alternative methods for cultivation of shellfish. Work with cities, counties, tribes, industries and management agencies in the Coast Range ecoregion on developmental planning efforts to ensure they consider their effects on nearshore habitats such as rainwater runoff, sedimentation, coastal squeeze, etc.

Limiting Factor:

Water Quality

CMP Direct Threats 1, 9, 11.2, 11.3, 11.4

Water quality degradation caused by human activities or natural causes may impact nearshore species and habitats. Water quality within the nearshore ocean is affected by coastal and inland development, either from increased runoff of contaminated water or increased water temperature resulting from altered hydrology or depth (e.g., dredging, filling). Boating activity in nearshore waters or adjacent estuaries may lead to accumulation of oil in surface waters from poorly maintained or failing equipment. Pollution due to other toxic chemicals from both point sources and non-point sources can degrade water quality. Contamination by fecal indicator bacteria degrades water quality. Water quality may be further degraded if conditions support significant blooms of harmful algae, which can lead to highly concentrated marine biotoxins. Ocean acidification and hypoxia both degrade water quality in the nearshore. Runoff from pavement, agricultural lands, and forests can all degrade water quality.

Recommended Approach

Coordinate with the multiple state and federal agencies involved in water quality issues to update and improve signage at marinas and public beaches to inform boaters and beach users about water quality issues and methods for reporting problems. Develop incentive programs to encourage boaters to use environmentally friendly gear or equipment. Prevent contamination and enforce laws regarding pollution and water quality issues. Monitor for harmful algal blooms to diagnose potential indications of domoic acid or paralytic shellfish poisoning. Work with the Department of Environment Quality (DEQ) in their monitoring efforts to continue and expand their assessments of water quality in the marine environment and their annual integrated reports which now include ocean acidification and hypoxia. Work with cities, counties, Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), and coastal industries to address rainwater runoff and sedimentation. Additional activities are needed to map and monitor the spatial distribution and extent of native eelgrass in both the intertidal and subtidal zones of Oregon estuaries.

Limiting Factor:

Harvesting Aquatic Resources

CMP Direct Threats 5.4, 9.4

Accurate accounting of abundance and harvest impacts is an important component of sustainable resource management. However, abundance estimates, and complete life history information needed to model abundance remains unknown for many nearshore species. Yet many nearshore species are targeted by fisheries. Populations of nearshore species may be impacted and limited by commercial or recreational overharvest at local or at broader scales, as well as through bycatch and discard of non-targeted species. Entanglement of whales and sea turtles is one form of bycatch, defined as incidentally affected species that are not retained, that people often do not think about. These interactions can cause death as well as non-lethal effects that can limit populations of these species.

Recommended Approach

Provide opportunities for protecting and enhancing nearshore fisheries stocks. Develop and implement fish release methods designed to minimize discard mortality. Increase the ODFW representation at sportsmen shows, festivals, and other venues, encourage fishers to avoid vulnerable species, and make information about proper discard techniques widely available. Develop monitoring, conservation, resource analyses, and harvest management plans for commercially and recreationally harvested shellfish. Evaluate immediate and long-term conservation and harvest management needs for Oregon’s recreational and commercial nearshore fisheries. Develop stock assessment and/or stock status indicator strategies for priority nearshore groundfish and shellfish species, designed to accommodate the unique circumstances and habitats of nearshore species with the greatest management need. Develop fishery-independent survey methodologies and gather baseline information for all key nearshore species. Review the SGCN list to identify priority species in need of conservation plans under Oregon’s Native Fish Conservation Policy. Collaborate with sport and commercial fishermen, university researchers, and others to gather imperative information for exploited nearshore stocks. Sponsor socioeconomic analysis of coastal communities to determine the relationship between stock status and direct (e.g., fishing) or indirect (e.g., tourism) impacts from various industries.

Limiting Factor:

Monitoring and Research Needs

Monitoring species and habitat changes will help evaluate resource status and trends over the long-term. Although some monitoring is done at present, more is needed to examine changes and trends within Oregon’s nearshore ecosystem. More data are needed to understand local and regional ecological changes due to predator-prey population dynamics, the introduction of non-native species, algae blooms, climate change, ocean acidification and hypoxia effects, and other changes. Many aspects of Oregon’s Nearshore Habitats and nearshore species are poorly understood. For many marine species, substantial data gaps exist with regards to population abundance and trends, population structure, life history parameters, responses to environmental changes, and species-habitat associations. Similarly, while significant strides have been made toward describing and mapping nearshore habitats, gaps remain for parts of the nearshore area. In addition, researchers are still accumulating data to describe the physical properties and biological components of certain habitat types, and to provide long-term information on the physical response of nearshore systems to climate change. More information is needed to assess and understand the complexity of the nearshore ecosystem and the effects of human interactions.

Recommended Approach

Encourage and assist in monitoring the population dynamics and habitat usage of rocky reef-associated species. Research the movement, behavior, and predator-prey relationships of adult and juvenile stages of nearshore species. Identify and evaluate conflicts between marine mammals and fisheries. Inventory and monitor non-native species. Public users should inspect boats, clothing, and equipment for non-native species before and after use of natural areas or waterbodies and should report sightings to support ongoing monitoring of species distribution. Assess and gather baseline information on levels of human use and disturbances to intertidal habitats, animals, and plants. Review coastal development plans and regulations to identify opportunities to address areas with consequent negative impacts to nearshore resources. Improve and expand the capabilities of research and monitoring programs to meet the requirements of the Native Fish Conservation Policy and other nearshore resource management programs. Investigate the effects of environmental changes on nearshore species and nearshore habitats. Continue to study, evaluate, and monitor harmful algal blooms to provide an early warning system for blooms. Continue to develop non-lethal habitat surveys of nearshore species and collaborate with interested stakeholders to increase survey coverage.

Limiting Factor:

NEARSHORE RECOMMENDATIONS

Recommended Approach

The following set of recommendations, intended to facilitate voluntary, collaborative actions to improve understanding and stewardship of Oregon’s nearshore resources, is the core of the information provided for the Nearshore ecoregion. These recommendations reflect the input received from the ODFW’s staff, outside experts who served as technical advisors and reviewers, and members of the public. Twelve recommendations are outlined below, categorized into three main themes: 1)Education and Outreach, 2)Research and Monitoring, and 3)Management and Policy. These are all important and not listed in a prioritized manner. Each recommendation was chosen because it addresses priority nearshore issues in need of immediate or timely attention, is feasible, has received public support, and is beyond the capability of any single institution to achieve. The recommendations rely on partners to differing degrees and are intended to help guide collaboration rather than act as an action plan for ODFW alone.

The description of each recommendation includes:

Recommendation: A brief statement of the recommended action.

Rationale: Conservation and/or management need(s) addressed by this recommended action, and strategies to achieve results. Recommendations are based on the known and/or potential factors affecting nearshore resources and resource sensitivity, as identified by public input, scientific information, technical advisors, and the ODFW staff.

Potential Partners: Who should—or could—be involved? A general list (not necessarily comprehensive) of potential partners for collaboration on implementation.

Category: Education and Outreach

A well-informed public helps drive policy and management decisions that support a heathy ecosystem and the many benefits it offers. The following recommendations are designed to enhance public awareness of nearshore species and habitats and foster public engagement in nearshore conservation issues.

(1) General Public, Constituent and Advisory Group Engagement

Recommendation: Develop and expand creative avenues to engage a diverse array of constituents, including the broader general public, on nearshore resource issues. Explore technologies that support alternative methods of communication and participation, in addition to continuing to support traditional paths such as issue-specific advisory groups.

Rationale: Input from informed and engaged partners is essential to successfully developing and implementing research, management/policy, and outreach on all natural resource issues. The exchange of information between ODFW and constituents improves understanding and support on both sides and aligns management with public priorities. Advisory committees can provide focused, in-depth engagement in selected aspects of nearshore management and research. In addition, there is a growing need to augment traditional methods of public input to reach an increasingly dispersed and diverse population of constituents interested in nearshore issues. ODFW has begun using new options for engaging the public and exchanging information, e.g., opportunities for online participation in public meetings and online surveys, and these have shown promise as effective tools for enhancing traditional methods.

Potential Partners: ODFW, existing advisory bodies, the general public, sport and commercial fishing interests, non-governmental organizations, tribes, Oregon Sea Grant, and various other communities of interested parties with a broad and diverse representation.

(2) Nearshore Resources Outreach Information, Access and Awareness

Recommendation: Broaden outreach materials and information available electronically, to deepen public appreciation of Oregon’s nearshore environment. Increase the quantity, quality, and timeliness of information available on ODFW’s website on nearshore fisheries, regulations, conservation and ecosystem management.

Rationale: Oregon’s nearshore is one of the richest ecological systems in the world, home to thousands of species in a multitude of habitat types. While there is much to learn about this incredible ecoregion, there is a wealth of existing information that could be used more effectively to fuel public interest in natural resource issues, and stewardship of those resources. Populating educational exhibits, websites, social media, and other media outlets with information about Oregon’s nearshore will deepen Oregonian’s connection to the outdoors and to wildlife. Photographs, videos, and stories, provided through a variety of sources and outlets will engage the public in the short-term, and build partnership and stewardship in the long-term.

Potential Partners: State and federal natural resource agencies, universities, Oregon Sea Grant, public aquaria and museums, non-governmental organizations, tribes, news outlets, and others.

(3) Communications Partnerships

Recommendation: Develop and expand existing partnerships for communication, education, and outreach on nearshore topics and issues. Work with partners to create new ways of developing and sharing information, and use these partnerships to reach new audiences. This includes developing best conservation and management practices where possible, sharing information about existing rules, and encouraging voluntary compliance through targeted outreach efforts.

Rationale: Conservation and management actions are better trusted and publicly supported when they are developed with stakeholders who understand nearshore issues. Partnering with groups that have a rich history of developing science-based education and outreach programs effectively and efficiently amplifies the quality and scope of nearshore resource communication and builds relationships and capacity outside of ODFW on nearshore resource issues. Through these partnerships, Oregon’s understanding of nearshore issues – and clarity on what members of the public can do to contribute to a healthy nearshore ecosystem – would facilitate a renewed spirit of engagement and commitment to nearshore resource stewardship.

Potential Partners: State and federal natural resource agencies, universities, Oregon Sea Grant, public aquaria and museums, non-governmental organizations, tribes, and others.

Category: Research and Monitoring

Expanded research and monitoring activities are required to generate data and information to meet the needs of resource managers. This is especially true in the nearshore area where human activity is intense and information on many species and their habitats is sparse. The Appendix – Nearshore Research and Monitoring lists some key data elements and examples of projects that would help support resource management. The following recommendations address research and monitoring program priorities for collaborative, multi-institutional issues. The broad objectives in this category are far beyond the capability of any one institution to fully achieve and therefore require partnerships to realize meaningful results.

(4) Ecosystem Response to Climate Change

Recommendation: Develop and implement research and monitoring efforts to understand, track, and work toward predicting effects of climate change and increased carbon dioxide on Oregon’s nearshore species and ecosystems. Focus research on species and ecosystems most at risk, and foster collaboration between scientists and managers to optimize research outcomes for use in management and conservation.

Rationale: Oregon’s ocean is already experiencing effects of climate change and increased carbon dioxide, including ocean acidification, hypoxia, other changes in water chemistry, warming ocean temperature, and changes in upwelling and other characteristics of the nearshore ocean and estuaries. These changes will continue to grow and intensify in the future. Oregon’s upwelling ecosystem is experiencing many of these changes sooner and in greater magnitude than other parts of the nation, increasing the urgency for collecting the needed information and formulating the necessary management response. This is a global problem that requires rigorous scientific information to solve, and partnership between scientists inside and outside of agencies to both understand the phenomena and try to mitigate its effects. Desired outcomes are to increase ecosystem and community resilience and the sustainability of Oregon’s nearshore resource.

Potential Partners: State and federal natural resource agencies, universities, local governments, non-governmental organizations, shellfish and fishing interests, tribes and others.

(5) Ecosystem Characterization – Species and Habitats

Recommendation: Continue and expand research and monitoring efforts on nearshore species and habitats. Gather scientific information on the abundance and distribution of species and habitats, the interactions among species and between species and their physical environment, and changes in those resources and interactions over time. The SGCN species information and Appendix – Nearshore Research and Monitoring needs provide guidance for setting research and monitoring priorities.

Rationale: Management of nearshore resources is most effective when based on a sound scientific understanding of the nearshore ecosystem. While there has been a great deal of research on Oregon’s nearshore ocean and natural resources, there remain significant data gaps that, once filled, will reduce uncertainty in resource management. ODFW gathers information on nearshore fish, invertebrates, marine mammals and habitats. In addition, ODFW monitors changes in marine reserves and nearby comparison areas, providing a unique opportunity to examine changes that occur to nearshore species in areas that are closed to fishing compared with similar areas where fishing occurs. These ODFW programs, along with numerous efforts undertaken by universities, resource agencies, and other partners need to be continued and expanding to produce information necessary to meet resource management challenges.

Potential Partners: State and federal natural resource agencies, universities, non-governmental organizations, fishing interests, tribes, and the general public.

(6) Fishery Independent Surveys

Recommendation: Develop methods for surveying fishery species in the nearshore environment with the goal of collecting fish and shellfish abundance data useful in assessing the status of harvested fish and shellfish stocks. Once methods are developed, conduct periodic fishery-independent surveys in the nearshore environment to produce data useful in stock assessments and develop long-term datasets that can indicate trends in abundance over time.

Rationale: The status of fishery stocks needs to be assessed periodically to ensure that fishery managers set appropriate catch limits and to provide sustainable harvest into the future. Stock assessments are often based on a combination of data collected from fishery landings and fishery-independent surveys of fish populations. Fishery-independent data are crucial to fine-tune and ground truth stock assessment models, helping to ensure assessment results most accurately reflect real-world fish abundance. These more accurate results allow managers and fishermen to have more certainty with management decisions and reduce the risk of deviating from conservation targets.

There are currently no fishery-independent surveys for most fish species targeted by nearshore fisheries. Many of these species are caught on nearshore rocky reefs, an environment that presents challenges to conventional fish survey methodology (e.g., trawl surveys). Methods need to be developed for conducting fish surveys in nearshore rocky reef areas that will produce consistent and reliable results useful in assessing stocks. Surveys then need to be conducted on a periodic basis and continued over a long time period to be useful in supporting stock assessments. The initial focus should be on nearshore rocky reef fish species, including black, blue, deacon, China, copper, quillback, and other rockfish species, as well as kelp greenling and cabezon.

Potential Partners: Fishery managers, stock assessment scientists, commercial and sport fishing interests, tribes, non-governmental organizations and university scientists.

(7) Nearshore Species Stock Assessments

Recommendation: Improve stock assessments and/or stock status indicators for priority data-limited nearshore fish and shellfish species to improve confidence in population estimates and management strategies. Develop and improve data collection programs needed to support nearshore species stock assessments including developing fishery-independent surveys (see Recommendation 6) and evaluate and improve existing fishery monitoring programs that record fishery catch/landings, estimate fishery effort, and collect biological data on landed catch.

Rationale: There is limited information about nearshore fish and shellfish populations available for use in population assessments. Data and monitoring have not been adequate to confidently assess stock status on many nearshore species, and there is currently no mechanism for indicating a population decline for many species. Developing stock assessment and/or indicator strategies, along with collecting the data necessary to implement the strategies, is essential to maintain confidence in management decisions and ensure sustainable harvest.

Potential Partners: ODFW, NOAA stock assessment scientists, other state and federal fishery resource agencies, tribes, university scientists, and the fishing industry.

(8) Human Dimensions Research and Monitoring

Recommendation: Conduct and support studies of social and economic patterns and trends as they relate to nearshore resources, human use of the resources, and effects of resource management actions on individuals, user groups, or communities. Potential topics include coastal community demographic trends, economic and social contributions of industries that depend on nearshore resources directly (e.g., fishing) or indirectly (e.g., tourism), and the impacts of regulatory and other management changes, including those that address climate change effects on coastal communities. In some cases, new methods will need to be developed to study these topics and develop data useful for resource management.

Rationale: Human dimensions information is central to understanding the context of natural resource issues and how people, coastal communities, economies, and nearshore resources are interrelated and might be affected by various management actions and policy choices. The social and economic benefits and consequences of resource management and policy actions including spatial planning need to be an integral part of the process. Gaining a better understanding of how to engage diverse communities and cultures to effectively participate in shaping policy is becoming increasingly important. There is a complex mix of conservation, sustainable harvest, land use practices, and social wellbeing that go into such decisions. One example is how to effectively and proactively address the impacts of climate change in a timely manner. Another example is ODFW’s marine reserves program ongoing human dimensions work about Oregon’s coastal communities evaluating marine reserves as a management tool that increases our general understanding Oregon’s coastal communities and user groups.

Potential Partners: State and federal natural resource agencies, university scientists, non-governmental organizations, the fishing industry, tribes, and the general public.

(9) Marine Mammal-Human Interactions

Recommendation: Continue and expand efforts to gather necessary information to manage resource conflicts between marine mammals and people in Oregon’s nearshore ocean, estuaries, and rivers. Information needed includes ongoing monitoring of population abundance, research on feeding habits and foraging behavior, research on predation impacts to fish populations, evaluation of conflicts with fisheries and methods to reduce them, and research on how to mitigate negative effects of human activities on marine mammals.

Rationale: Many marine mammal species in the Pacific Northwest, under the protection of the federal Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, have enjoyed a marked recovery of their populations. In some cases, the substantial increase in the number of pinnipeds along the coast and in the lower Columbia River has resulted in widespread negative impacts to fish species of conservation concern such as ESA-listed salmon and steelhead, white sturgeon and Pacific lamprey, as well as conflicts with sport and commercial fisheries. As an example, the eastern stock of Steller sea lions has experienced a successful recovery and was delisted under the Endangered Species Act. Similarly, some populations of cetaceans like gray whales and humpback whales have increased. While these are conservation success stories, the increase has resulted in increased resource conflicts throughout their range. To address conflicts created by increasing marine mammal populations, it is essential to monitor these populations, examine food habits, foraging behavior, and predation effects on fish populations, and evaluate conflicts with fisheries and other human activities and how best to mitigate them.

Potential Partners: ODFW, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, sport and commercial fishing interests, tribes, port districts, and other state and local government entities.

Category: Management and Policy

Good governance for natural resources is built from a transparent management framework, trust from stakeholders, and sound science. Resource sustainability and resilience to a changing environment is improved with good management, good policy, and good governance. The recommendations in this category address priority nearshore issues and species using a variety of non-regulatory tools.

(10) Management Response to Climate Change

Recommendation: Promote use of climate change information in management decision-making and policy development in statewide, regional and global arenas. Build climate resilience and climate change adaptation into decision-making to maximize the long-term benefits of today’s public investment in natural resource management.

Rationale: Our understanding of climate change continues to broaden and deepen, as we discover the multitude of climate change symptoms and explore predictions of future impacts. Symptoms include those that have been in the public awareness for decades (e.g. warming temperatures) as well as newly identified phenomenon such as ocean acidification, which was first recognized in 2003. Many (or arguably most) natural resource management tools do not explicitly incorporate climate change information; at best, management tools include methods for addressing scientific uncertainty (e.g. harvest quota estimates), which may indirectly account for some degree of climate change uncertainty, but not all of it. Decisions made today on natural resource issues – made in a vacuum relative to climate change adaptation information – likely will not stand the test of time. Poor decisions today, assuming a static environment, will likely lead to destabilization of businesses, and economies that rely on resource availability for harvest, tourism or other purposes.

Potential Partners: State and federal natural resource agencies, university scientists, non-governmental organizations, tribes, and the fishing industry.

(11) Marine Fishery Management Plans

Recommendation: Build the information/datasets and stakeholder support for state marine fishery management plans for appropriate nearshore SGCN and Watch List species (see Appendix – Nearshore Species).

Rationale: Transparent documentation of management strategies can lead to increased public engagement in management (particularly increased public input) and improved information for decision-making processes. Both lead to greater public confidence that Oregon’s natural resources are healthy and well-managed. To facilitate transparency and improve information in decision-making, ODFW has developed the Marine Fishery Management Plan Framework (2015) – an approach to developing Fishery Management Plans (FMPs) for nearshore and other marine species, developed under the umbrella of the Native Fish Conservation Policy. The goal of the Framework is to create a common understanding of what can and/or should be part of state FMPs and lay out a publicly transparent road map for how to develop marine FMPs. The real heart of the Framework is in the building of individual FMPs, each of which will be adopted by the Fish and Wildlife Commission. Building each individual FMP will be time-consuming and labor-intensive, both for agency staff and for the public, whose input will be necessary for the FMPs to be rigorous and effective.

Potential Partners: State and federal natural resource agencies, sport and commercial fishing interests, non-governmental organizations, university scientists, tribes, and the general public.

(12) Marine Planning

Recommendation: Participate in marine planning processes to ensure Oregon’s interests in marine natural resource conservation and use are fully represented in marine policy. Develop marine natural resource spatial information and incorporate it into marine planning processes to ensure they use the best available science to formulate plans concerning Oregon’s marine resources and uses (see Land Use Changes KCI). There are many processes underway that are specifically focused on the marine environment, both within the state and outside of state boundaries that may affect Oregon’s nearshore waters, species and habitats.

Rationale: Growing demand for ocean resources and competing use of ocean space has increased the need to move beyond single-sector management and plan for ocean uses more holistically. Marine planning processes require comprehensive spatial information on location, abundance and distribution of marine resources and resource uses. Spatial data that meet these needs have not been developed for many marine resources and require collaborative efforts and funding to ensure full development. Marine planning efforts engage multiple users, governments, and management agencies to ensure continued sustainability of ocean resources, while providing for a diverse array of uses and public priorities. Alongside many collaborators and partners, ODFW participated in the state’s development and modifications of the Territorial Sea Plan, which outlines state policy on its Territorial Sea including spatial planning that may affect marine life and their habitats. Several marine planning processes affecting Oregon are currently underway at the federal level. While these are in federal waters, they still affect Oregon’s nearshore marine resources and Oregon’s ocean users. ODFW will continue to play a key role in providing natural resource information to support these processes, as well as ensuring Oregon’s nearshore resources and ocean user groups are represented in policy decisions. ODFW will also play an ongoing role in plan implementation and keeping marine resource data sets current, and relevant, as new information becomes available.

Potential Partners: State and federal natural resource agencies, sport and commercial fishing interests, local, state, regional, and federal governments, community groups, non-governmental organizations, tribes, and the general public.

Strategy Species

Big Skate

Beringraja binoculata

Black Brant

Branta bernicla nigricans

Black Oystercatcher

Haematopus bachmani

Black Rockfish

Sebastes melanops

Blue Mud Shrimp

Upogebia pugettensis

Blue Rockfish

Sebastes mystinus

Brown Pelican

Pelecanus occidentalis californicus

Brown Rockfish

Sebastes auriculatus

Bull Kelp

Nereocystis luetkeana

Cabezon

Scorpaenichthys marmoratus

California Mussel

Mytilus californianus

Canary Rockfish

Sebastes pinniger

Caspian Tern

Hydroprogne caspia

China Rockfish

Sebastes nebulosus

Chum Salmon, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus keta

Chum Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus keta

Coastal Cutthroat Trout

Oncorhynchus clarki clarki

Coho Salmon, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Coho Salmon, Klamath SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Coho Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Coho Salmon, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Copper Rockfish

Sebastes caurinus

Deacon Rockfish

Sebastes diaconus

Dungeness Crab

Metacarcinus magister

Eulachon

Thaleichthys pacificus

Fall Chinook Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Fall Chinook Salmon, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Fall Chinook Salmon, Snake SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Flat Abalone

Haliotis walallensis

Fork-tailed Storm-Petrel

Oceanodroma furcata

Grass Rockfish

Sebastes rastrelliger

Gray Whale

Eschrichtius robustus

Green Sturgeon, Northern DPS

Acipenser medirostris

Green Sturgeon, Southern DPS

Acipenser medirostris

Harbor Porpoise

Phocoena phocoena

Kelp Greenling

Hexagrammos decagrammus

Killer Whale

Orcinus orca

Leach’s Storm-Petrel

Oceanodroma leucorhoa leucorhoa

Lingcod

Ophiodon elongatus

Longfin Smelt

Spirinchus thaleichthys

Marbled Murrelet

Brachyramphus marmoratus

Native Eelgrass

Zostera marina

Native Littleneck Clam

Leukoma staminea

Northern Anchovy

Engraulis mordax

Northern Elephant Seal

Mirounga angustirostris

Ochre Sea Star

Pisaster ochraceus

Olympia Oyster

Ostrea lurida

Pacific Giant Octopus

Enteroctopus dofleini

Pacific Harbor Seal

Phoca vitulina

Pacific Herring

Clupea pallasii

Pacific Lamprey

Entosphenus tridentatus

Pacific Sand Lance

Ammodytes personatus

Pile Perch

Rhacochilus vacca

Purple Sea Urchin

Strongylocentrotus purpuratus

Quillback Rockfish

Sebastes maliger

Razor Clam

Siliqua patula

Red Abalone

Haliotis rufescens

Red Sea Urchin

Mesocentrotus franciscanus

Redtail Surfperch

Amphistichus rhodoterus

Rock Greenling

Hexagrammos lagocephalus

Rock Sandpiper

Calidris ptilocnemis tschuktschorum

Rock Scallop

Crassadoma gigantea

Sea Palm

Postelsia palmaeformis

Shiner Perch

Cymatogaster aggregata

Spiny Dogfish

Squalus suckleyi

Spring Chinook Salmon, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Lower Snake SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Upper Snake SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Willamette SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Starry Flounder

Platichthys stellatus

Steller Sea Lion

Eumetopias jubatus

Striped Perch

Embiotoca lateralis

Sunflower Star

Pycnopodia helianthoides

Surf Grass

Phyllospadix spp.

Surf Smelt

Hypomesus pretiosus

Tiger Rockfish

Sebastes nigrocinctus

Topsmelt

Atherinops affinis

Tufted Puffin

Fratercula cirrhata

Vermilion Rockfish

Sebastes miniatus

Western River Lamprey

Lampetra ayresii

Western Snowy Plover

Charadrius nivosus nivosus

White Sturgeon

Acipenser transmontanus

Wolf-eel

Anarrhichthys ocellatus

Yelloweye Rockfish

Sebastes ruberrimus

Yellowtail Rockfish

Sebastes flavidus