Description

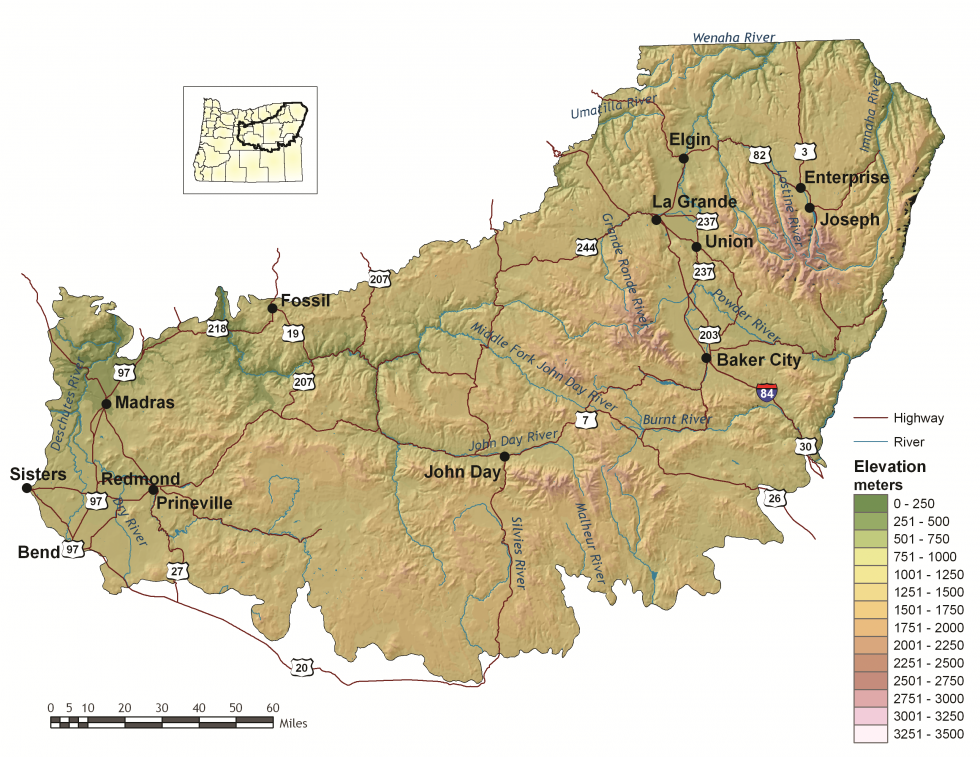

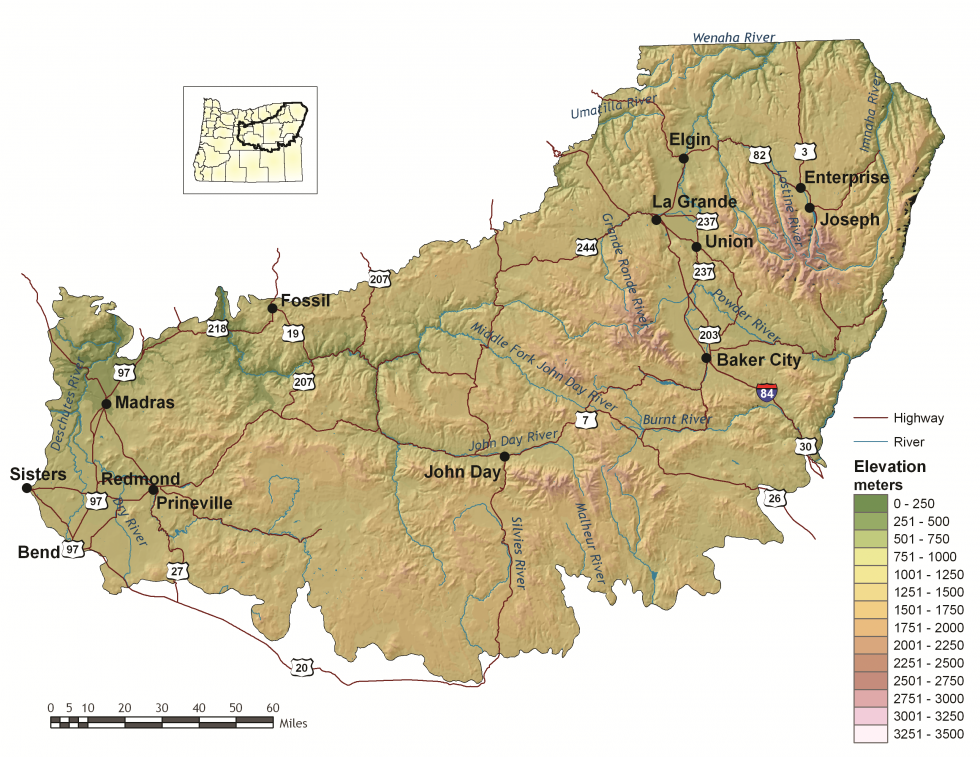

At 23,984 square miles, the Blue Mountains ecoregion is the largest ecoregion in Oregon. The Blue Mountains ecoregion is a diverse complex of mountain ranges, valleys, and plateaus that extends beyond Oregon into the states of Idaho and Washington. This ecoregion contains deep rock-walled canyons, glacially cut gorges, sagebrush steppe, juniper woodlands, mountain lakes, forests, and meadows. Broad alluvial-floored river valleys support ranches surrounded by irrigated hay meadows and agricultural fields. The climate varies because of elevational differences but, overall, the ecoregion has short, dry summers and long, cold winters. Because much of the precipitation falls as snow, snow melt gives life to the rivers and irrigated areas.

Wood products and cattle production dominate the economy of the ecoregion, but agriculture along river valleys supports a variety of crops. The ecoregion sustains some of the most robust ungulate populations in the state and attracts tourists year-round, offering scenic lakes and rivers, geologic features, alpine areas, and numerous wildlife viewing opportunities. It includes the Prineville-Bend-Redmond metropolitan area, one of the fastest growing areas in the state, along with the cities of La Grande, Baker, Enterprise, and John Day.

Characteristics

Important Industries

Agriculture, livestock (e.g., beef cattle, dairy cattle, sheep), forest products, manufacturing, outdoor recreation (e.g., hunting, fishing, skiing, camping, wildlife viewing)

Major Crops

Wheat, alfalfa, grass seed, meadow hay, potatoes, onions, sugar beets, field corn

Important Nature-based Recreational Areas

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Hells Canyon National Recreational Area and Hells Canyon Wilderness, Wallowa Lake, Crooked River National Grasslands. Umatilla National Wildlife Refuge, John Day and Grande Ronde Rivers, Lake Billy Chinook, and Smith Rock State Park. Black Canyon, Mill Creek, Eagle Cap, Strawberry Mountain, North Fork John Day and Wenaha-Tucannon Wilderness Areas. Philip W. Schneider, Bridge Creek, Ladd Marsh, Wenaha, Elkhorn, and Minam Wildlife Areas.

Elevation

1,000 feet (Snake River) – 9,838 feet (Sacajawea Peak)

Important Rivers

Deschutes, Crooked, Burnt, Grande Ronde, Imnaha, John Day, Malheur, Powder, Silvies, Snake, Umatilla, Wallowa

Ecologically Outstanding Areas

Malheur headwaters, Bear Valley, and the Umatilla-Walla Walla headwaters

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor:

Land Use Conversion and Urbanization

CMP Direct Threats 1, 2.1, 2.3, 7.2

The western portion of the Blue Mountains ecoregion includes the cities of Madras, Redmond, Prineville, and eastern Bend, one of the fastest growing metropolitan areas of the state. Rapid conversion to urban land uses threatens habitats and traditional land uses such as agriculture. Impacts to mule deer winter range are of particular concern. Northeast Oregon is increasingly popular with travelers, and habitat fragmentation due to rural development and recreation is a concern in some areas. While important economically, some agricultural uses contribute to habitat degradation for native fish and wildlife species. For example, open grazing allotments in forests have significantly damaged understory and riparian habitat in several areas.

Although many acres in this ecoregion are managed for wildlife and recreational values, these areas are primarily limited to higher mountain forests and alpine areas, or steep canyonlands. Lower elevation vegetation types, such as valley bottom grasslands, riparian areas, wetlands, and shrublands, are mostly on private lands. Most remnant low-elevation native habitats occur as fragmented patches with poor connectivity.

Recommended Approach

Because important low-elevation habitats are primarily privately-owned, working with private landowners and local governments on voluntary cooperative approaches to improve habitat is the key to long-term conservation. Tools such as financial incentives, regulatory assurance agreements, and conservation easements may help landowners take actions to benefit species and habitats. Where feasible, maintain and restore habitats using a landscape approach to increase connectivity between habitat patches. Work with community leaders and local governments to ensure ecologically and environmentally conscientious growth. Support and implement existing land use regulations to preserve farmland and rangeland, open spaces, recreation areas, and natural habitats. Coordinate with local SWCDs, watershed councils, NRCS, and NGOs to communicate the importance of managing fish and wildlife habitats on private lands.

On public lands, unsustainable grazing should be curtailed. Federal land managers should develop adaptive grazing management plans that limit stocking rates based on ecological conditions and implement rotational grazing among allotments to allow for vegetation recovery. Incorporating emerging technologies like virtual fencing can help manage herd distribution more precisely, keeping animals out of riparian zones or other sensitive ecological areas without the need for physical barriers. Restoration activities can also improve habitat on degraded rangelands through removal of invasive species and reseeding with native vegetation.

Limiting Factor:

Altered Fire Regimes

CMP Direct Threats 7.1, 11.3, 11.4

In ponderosa pine habitat types, fire suppression and past forest practices have resulted in young, dense mixed-species stands where open, park-like stands of ponderosa pine once dominated. Increasing encroachment by smaller Douglas-firs and true firs places the forest at greater risk of severe wildfire, disease, and damage by insects. The spread of native junipers and non-native annual grasses throughout the ecoregion has also significantly increased fuel loads. Wildfire risk is further exacerbated by warming climate conditions and changes to patterns of precipitation, resulting in more frequent, higher intensity megafires. Dense understories and insect-killed trees make it difficult to reintroduce natural fire regimes because hazardous fuel levels increase the risk of stand-replacing fires. Additionally, young forests are often lacking in mature trees and snags that serve as critical wildlife habitat for some species. Efforts to reduce fire danger and improve forest health may help to restore habitats but require careful planning to provide sufficient habitat features that are important to fish (e.g., large woody debris, riparian vegetation) and wildlife (e.g., snags, downed logs, hiding cover). Similarly, wildfire reforestation efforts should be strategically planned to create stands with a diversity of tree age classes, understory vegetation, and natural forest openings.

Recommended Approach

Use an integrated approach to forest health issues that considers historical conditions, fish and wildlife conservation, natural fire intervals, and silvicultural techniques. Encourage forest management at a broad scale to address limiting factors. Implement fuel reduction projects to reduce the risk of forest-destroying wildfires, considering site-specific conditions and goals. Fuel reduction strategies need to address the habitat structures that are important to wildlife, such as snags and downed logs, and work to maintain them at a level to sustain wood-dependent species. Reintroduce fire where feasible; prioritize sites and applications where intervention is likely to be most successful. Use prescribed burns to enhance quality of forage and cover for a diversity of species. Where fire is not feasible, explore alternatives, such as thinning and masticating, that can help mimic natural disturbance. Monitor forest health initiatives and use adaptive management techniques to ensure efforts are meeting habitat restoration and wildfire prevention objectives with minimal impacts on fish and wildlife. In the case of post-wildfire recovery, maintain high snag densities and replant with native tree, shrub, grass, and forb species. Manage reforestation after wildfire to create species and structural diversity, based on local management goals.

Limiting Factor:

Water

CMP Direct Threats 7.2, 11.4

Water quantity is a limiting factor for fish and wildlife. Changing climate conditions are leading to rising temperatures and altered patterns of precipitation, which affect water availability across different times of year. High demands for water, including for use in irrigation, can drastically reduce water availability. In streams, seasonal low flows due to changing climate conditions and over-allocation of water for agricultural uses can limit habitat suitability and reproductive success for many fish and wildlife species. In areas where urbanization is increasing, particularly in central Oregon around Bend, Madras, and Redmond, the demand for water is contributing to a decrease in the supply of groundwater. This reduces groundwater discharge of cold water to rivers and streams, subsequently reducing the availability of both cold water refugia and suitable habitat for cold-water dependent species. Water quality can also limit species and habitats. Runoff from agricultural areas can contaminate waterways. Warming temperatures, combined with higher nutrient levels due to agricultural runoff, is increasing the prevalence of toxic cyanobacterial blooms.

Recommended Approach

Provide incentives and information about water usage and sharing during low flow conditions (e.g., late summer). Promote water management actions that enable climate resilience and adaptation. Invest in watershed-scale projects for cold water and flow protection. Identify and protect cold water rearing and refugia habitat for aquatic species. Increase awareness and manage timing of applications of potential aquatic contaminants. Improve compliance with water quality standards and pesticide use labels administered by the DEQ and EPA. Work on implementing Senate Bill 1010 (Oregon Department of Agriculture) and DEQ Total Maximum Daily Load water quality plans.

Limiting Factor:

Invasive Species

CMP Direct Threat 8.1

Invasive plants and animals disrupt and degrade native communities, diminish populations of at-risk native species, and threaten the economic productivity of resource lands. Invasive plants, particularly noxious weeds, are easily spread and may quickly outcompete native species. While not as disruptive, invasive animals have caused problems for native fish and wildlife species and have become a nuisance and impacted people economically. In this ecoregion, unregulated horse herds, including the Murderers Creek herd and Big Summit herd, are of particular concern, competing with native wildlife for vegetation and access to water, and trampling sensitive riparian habitats. In aquatic habitats, smallmouth bass, walleye, brook trout and American bullfrogs are problematic invasives. Several mussel species, including zebra, quagga, and golden mussels, pose significant threats to aquatic systems. Non-native annual grasses, including cheatgrass, ventenata, and medusahead have rapidly expanded in perennial grass systems, displacing desirable forage for wildlife. Invasion of these species can also increase fuel loads by establishing in interspaces between sagebrush or other shrubs and perennial grasses, which were historically bare of vegetation.

Changing climate conditions and fire suppression have also led to the expansion of western juniper throughout the ecoregion. Western juniper is a native species, and old growth juniper trees in rocky outcrops offer benefits to native wildlife. However, the expansion of western juniper in the Blue Mountains has degraded some grassland, sagebrush, riparian, large-diameter juniper, and aspen habitats. Western juniper expansion may reduce water availability in many seasonal and some perennial streams. In riparian areas, junipers replace deciduous shrubs and trees that are more beneficial to riparian wildlife. In many of the grassland and sagebrush habitats, 20–30-year-old juniper trees form dense stands that are not suitable for many wildlife species that require the open sagebrush or grassland habitats that are now in decline. These dense stands also act as fuel for wildfire, contributing to large, high-intensity fires that destroy sagebrush habitat.

Recommended Approach

Promote dialogue between fish and wildlife managers, landowners, and land managers to develop management plans based on common priorities. Engage in outreach to educate the public on the negative impacts of invasive species and provide information on how to prevent invasions. Emphasize prevention, risk assessment, early detection, and quick control to prevent new invasive species from becoming fully established. Use multiple site-appropriate tools (e.g., mechanical, chemical, biological) to control the most damaging invasive species. Emphasize efforts to focus on key invasive species in high priority areas, particularly where Key Habitats and Species of Greatest Conservation Need occur. Cooperate with partners through habitat programs to reduce noxious weeds and other invasive species and to educate people about invasive species issues. Promote the use of native plants for restoration and revegetation. At some sites in sagebrush communities, it may be desirable to use “assisted succession” strategies, using low seed rates of non-invasive non-native plants in conjunction with native plant seeds as an intermediate step in rehabilitating disturbances.

Limiting Factor:

Recreational Activity

CMP Direct Threats 1.3, 6.1

Activities like hiking, biking, hunting, fishing, camping, skiing, and off-road vehicle use can create sensory stressors for wildlife, with sound, light, and unusual smells that may deter species from moving through certain areas. Many species will avoid areas near trails, campgrounds, and access roads when humans are present. Human recreation may contribute to destruction of sensitive vegetation, harassment of wildlife from off-leash pets, and contamination of areas with refuse. Dispersed recreation can cause new roads and trails to fragment the landscape and can cause the spread of invasive species from other locations.

Recommended Approach

Plan new recreational trail systems carefully and with consideration for native wildlife and their habitats. Take advantage of abandoned or closed roads, rail lines, or previously impacted areas for conversion into trails. Work with land management agencies, such as the USFS, to designate areas as high value recreation and low habitat impact areas. Limit the use of motorized vehicles in sensitive areas, including off-road vehicles and electric bicycles. Institute road and/or area closures to protect species during sensitive times of year and decommission roads when possible. In high use areas, establish permitted entry systems to decrease recreational pressure. Engage in outreach to educate the public on the negative impacts of recreational activities and provide information on prevention. Follow guidelines for responsible recreation, such as Leave No Trace, to minimize impacts.

Strategy Species

American Pika

Ochotona princeps

American Three-toed Woodpecker

Picoides dorsalis

Arrow-leaf Thelypody

Thelypodium eucosmum

Black-backed Woodpecker

Picoides arcticus

Bobolink

Dolichonyx oryzivorus

Bulb Juga

Juga bulbosa

Bull Trout, Deschutes SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Grande Ronde SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Hells Canyon SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Imnaha SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, John Day SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Malheur River SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Umatilla SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Walla Walla SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Burrowing Owl

Athene cunicularia hypugaea

California Myotis

Myotis californicus

Columbia Clubtail

Gomphus lynnae

Columbia Spotted Frog

Rana luteiventris

Columbian Sharp-tailed Grouse

Tympanuchus phasianellus columbianus

Cusick’s Lupine

Lupinus lepidus var. cusickii

Fall Chinook Salmon, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Fall Chinook Salmon, Snake SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Ferruginous Hawk

Buteo regalis

Flammulated Owl

Psiloscops flammeolus

Fringed Myotis

Myotis thysanodes

Gray Wolf

Canis lupus

Great Basin Redband Trout, Malheur Lakes SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii

Great Gray Owl

Strix nebulosa

Greater Sage-Grouse

Centrocercus urophasianus

Greenman’s Desert Parsley

Lomatium greenmanii

Hoary Bat

Lasiurus cinereus

Howell’s Spectacular Thelypody

Thelypodium howellii ssp. spectabilis

Lewis’s Woodpecker

Melanerpes lewis

Loggerhead Shrike

Lanius ludovicianus

Long-billed Curlew

Numenius americanus

Long-legged Myotis

Myotis volans

Macfarlane’s Four o’Clock

Mirabilis macfarlanei

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

Olive-sided Flycatcher

Contopus cooperi

Oregon Semaphore Grass

Pleuropogon oregonus

Pacific Marten

Martes caurina

Pallid Bat

Antrozous pallidus

Peck’s Milkvetch

Astragalus peckii

Pileated Woodpecker

Dryocopus pileatus

Purple-lipped Juga

Juga hemphilli maupinensis

Red-fruited Lomatium

Lomatium erythrocarpum

Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep

Ovis canadensis canadensis

Rocky Mountain Tailed Frog

Ascaphus montanus

Silver-haired Bat

Lasionycteris noctivagans

Snake River Goldenweed

Pyrrocoma radiata

South Fork John Day Milkvetch

Astragalus diaphanus var. diurnus

Spalding’s Campion

Silene spaldingii

Spotted Bat

Euderma maculatum

Spring Chinook Salmon, Lower Snake SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Upper Snake SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Summer Steelhead / Columbia Basin Redband Trout, Lower Snake SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri

Summer Steelhead / Columbia Basin Redband Trout, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri

Swainson’s Hawk

Buteo swainsoni

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat

Corynorhinus townsendii

Trumpeter Swan

Cygnus buccinator

Upland Sandpiper

Bartramia longicauda

Western Brook Lamprey

Lampetra richardsoni

Western Bumble Bee

Bombus occidentalis

Western Painted Turtle

Chrysemys picta bellii

Western Ridged Mussel

Gonidea angulata

Western Toad

Anaxyrus boreas

Westslope Cutthroat Trout

Oncorhynchus clarki lewisi

White-headed Woodpecker

Picoides albolarvatus

Wolverine

Gulo gulo

Conservation Opportunity Areas

Baker Valley Wetlands [COA ID: 165]

Located in the Powder River Basin immediately northwest of Baker City and including the town of Haines

Bear Valley [COA ID: 177]

Located south of John Day, along the Silvies River and including the town of Seneca. Area encompasses important wetland and riparian habitats in the valley.

Bully Creek Area [COA ID: 183]

Adjacent to North Fork Malheur – Monument Rock area, including significant stretches of Clover Creek and Bully Creek

Burnt River [COA ID: 166]

Includes important stretch of the Burnt River and adjacent riparian habitat. Includes the town of Bridgewater.

Deschutes River [COA ID: 149]

Mainly located on the Warms Springs Reservation, this narrow COA includes a section of the Deschutes River from above the confluence with the Warms Springs River, north to approximately 1.5 miles below White Horse Rapids. From east to west the COA runs from the east side of the Deschutes River, adjacent to White Horse rapids, …

East Madras-Trout Creek Sagebrush and Grassland Area [COA ID: 172]

Adjacent to Lower John Day COA, just east of the town of Madras.

Fields Peak [COA ID: 176]

Just north of Bear Valley COA and east of the South John day River COA

Grande Ronde Valley [COA ID: 159]

This COA encompasses the Ladd Marsh Wildlife Area and a buffered area adjacent to the Grande Ronde River from La Grande to several miles below Elgin.

Imnaha [COA ID: 161]

Follows canyons along the Snake River from Hwy 86 north to the ecoregion boundary

Lawrence Grasslands [COA ID: 152]

In the southwest corner of the ecoregion just west of Antelope.

Logan Valley-John Day River Headwaters [COA ID: 179]

Area just west of John Day and including the town of Prairie. Area encompasses the John Day River headwaters and a variety of diverse Strategy Habitats

Lower Deschutes River [COA ID: 148]

Follows the Lower Deschutes River Corridor and includes surrounding habitat.

Lower Grande Ronde [COA ID: 158]

This COA follows the Grande Ronde River from the Oregon/Washington border to its confluence with the Wallowa River, then continues up the Wallowa to Highway 82 and the Minam River confluence. It includes many of the smaller tributaries and significant portions of larger tributaries.

Lower John Day River [COA ID: 153]

Area follows the lower John Day River and surrounding habitats.

Malheur River Headwaters [COA ID: 180]

The Malheur River Headwaters COA spans two ecoregions. Within the BM ecoregion, the COA includes Logan Valley and part of the Strawberry Mountain Wilderness and continues south to Battle Mountain (just north of Highway 306). Within the NBR, the COA is comprised of land associated with the Malheur River south of Battle Mountain to approximately …

Metolius Bench-Mutton Mountains Wildlife Movement Corridor [COA ID: 150]

This long narrow COA spans two ecoregions. Within the East Cascades, it begins on the south side of the Metolius River, northwest of Lake Billy Chinook, and crosses over the river and into the Warm Springs Reservation. Heading north east, the COA crosses into the Blue Mountains ecoregion, across US Highway 26, and at its …

Middle Fork John Day River [COA ID: 170]

Includes significant stretch of Middle Fork John Day River, Long Creek, and part of the North Fork John Day River.

North Fork John Day River 1 [COA ID: 168]

Located at the border of Umatilla and Grant Counties, including the town of Ukiah, significant stretches of the North Fork of the John Day River, and Camas Creek

North Fork John Day River 2 [COA ID: 169]

To the east of North Fork John Day River 1, this area encompasses high quality habitat for Strategy Species surrounding John Day Wilderness Area and near the town of Granite.

North Fork Malheur-Monument Rock Area [COA ID: 182]

At the border of Baker and Grant Counties, following the North Fork Malheur River and adjacent to Monument Rock Wilderness

Ochoco Mountains [COA ID: 173]

Immediately adjacent to John Day River area, at the border of Wheeler and Crook Counties

Powder River Sage-Grouse Core Area [COA ID: 164]

Located immediately north of Pleasant valley, adjacent to Wallowa Mountains COA, including a significant stretch of the Powder River.

Rattlesnake Creek-Calamity Creek Area [COA ID: 181]

At the border of Grant and Harney County, area encompasses important sections of Rattlesnake Creek and Calamity Creek, immediately adjacent to the Silvies River COA

Rock Creek-Butter Creek Grasslands [COA ID: 155]

This is the largest COA within the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion extending from Rock Creek to Butter Creek, totaling 809 square miles.

Silver Creek Area [COA ID: 175]

Located at the southern edge of the Blue Mountains Ecoregion, just west of the Silvies River. Area includes ecologically significant stretch of Silver Creek and its surrounding habitat

South Fork Crooked River Area [COA ID: 174]

At the southern edge of the ecoregion, adjacent to several COAs and slightly west of the town of Burns

South John Day River [COA ID: 171]

Includes the mainstem John Day River and surrounding high quality fish and wildlife habitat. Southern part of area begins near Silvies River and continues north to the confluence near the town of Kimberly.

Upper Grande Ronde River Area [COA ID: 160]

The edge of this COA includes the Starkey Experimental Forest northwest of US Highway 244 and Camp Elkanah; and Starkey to the east before spreading south and encompassing the Fly Creek and upper Grande Ronde River watersheds.

Upper Silvies River [COA ID: 178]

Includes significant stretch of the Silvies River and surrounding habitat. Spans Blue Mountains (bounded at the north by the town of Seneca) and Northern Basin & Range Ecoregion (starting at Malheur Lake to the south), passing through the town of Burns

Walla Walla Headwaters [COA ID: 157]

This COA is mainly located within the Blue Mountains ecoregion of Umatilla, Union, and Wallowa Counties, but enters into a small section of the Columbia Plateau ecoregion along its northwest corner. Characterized by extensive mixed conifer forest, this rugged landscape also contains important native perennial grasslands, abundant springs, and abuts the North Fork Umatilla Wilderness …

Wallowa Mountains [COA ID: 163]

Located in northeastern Oregon adjacent to the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest.

Warner West [COA ID: 198]

This COA includes portion of Abert Rim Wilderness Study Area, Fish Creek Rim Wilderness Study Area, Lake Abert Area of Critical Environmental Concern, and the Fish Creek Rim Research Natural Area. It encompasses an area between Abert Rim and the Warner Mountains on the western edge to South Warner Rim and Lynches Rim to the …

Willow Creek-Birch Creek Area [COA ID: 167]

Located between the towns of Brogan and Huntington, at the eastern border of the ecoregion adjacent to the Snake River

Zumwalt Prairie Plateau [COA ID: 162]

At the eastern edge of the ecoregion northeast of Enterprise and Joseph, the area builds from TNC Zumwalt Prairie and extends northwest to include significant canyon and riparian habitat