Description

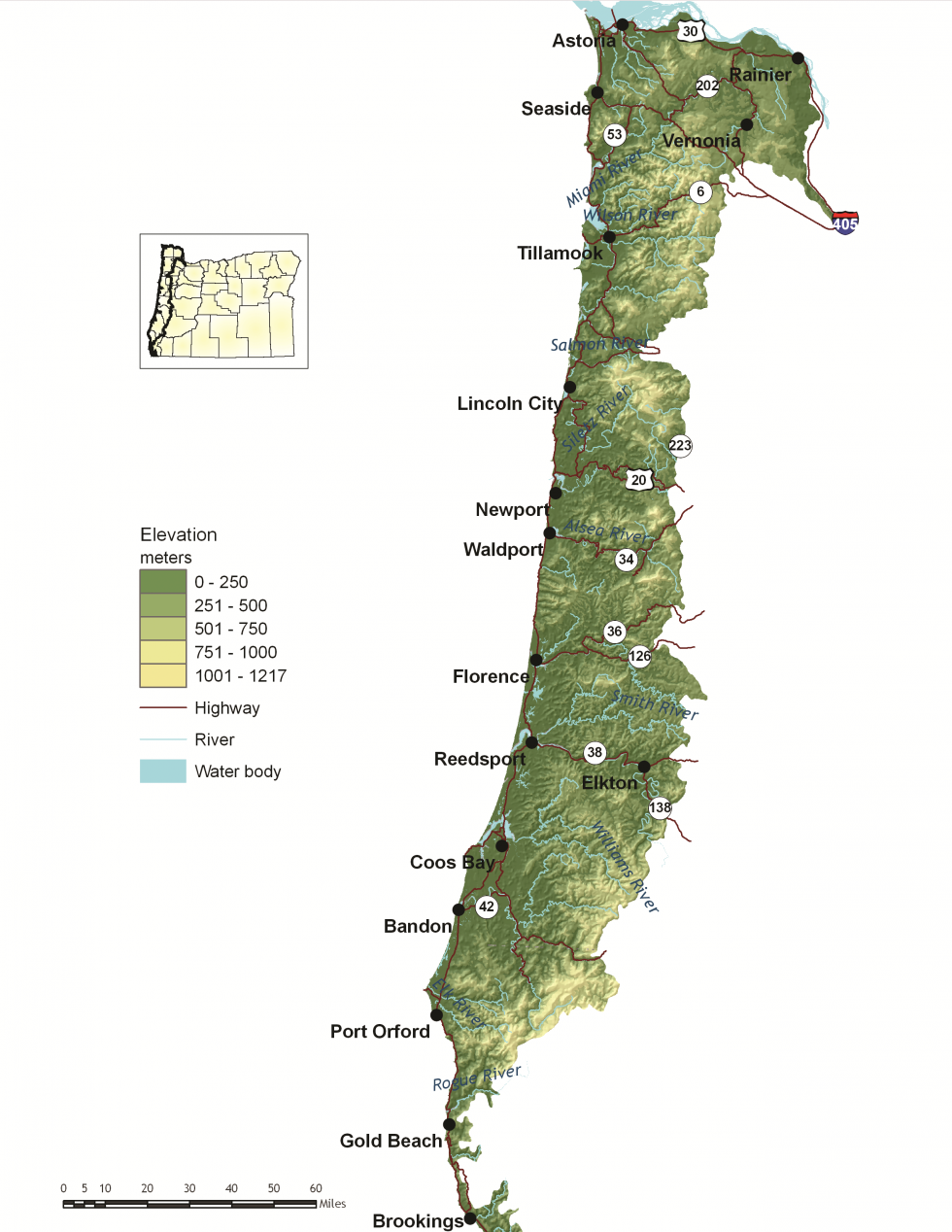

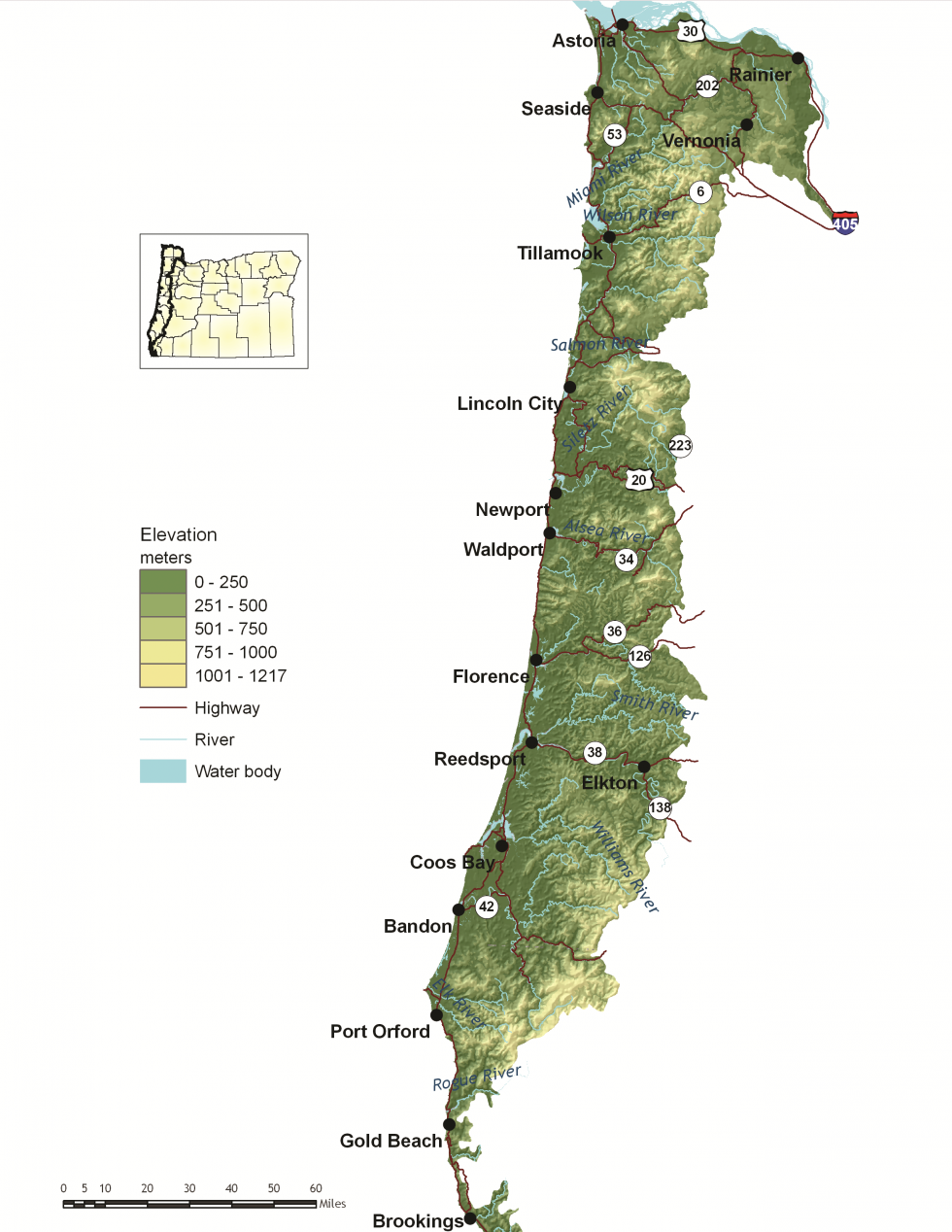

Oregon’s Coast Range ecoregion is known for its dramatic scenery. It is also extremely ecologically diverse, with habitats ranging from open sandy dunes to lush forests and from marshes to headwater streams. Along the coastline, habitats are directly influenced by the marine environment and include beaches, estuaries, and headlands. The Coast Range includes the highest density of streams found in the state, and deciduous riparian vegetation is distinct from surrounding coniferous forests. The Coast Range ecoregion includes the entire reach of the Oregon coastline, bordering the Nearshore ecoregion, and extends east through coastal forests to the border of the Willamette Valley and Klamath Mountains ecoregions.

The topography is highly variable, from coastal mountain ranges characterized by steep mountain slopes and sharp ridges to coastal lowlands. Elevation varies from sea level to Marys Peak, which is roughly 4,100 feet high; however, main ridge summits are approximately 1,400-2,500 feet.

The Coast Range’s climate is influenced by its topography and cool, moist air from the ocean, making it the wettest and mildest in the state. These conditions are ideal for Oregon’s highly productive temperate rainforests, which are important ecologically and for local economies. Most of the ecoregion is dominated by coniferous forests. Large forest fires are historically infrequent but are severe when they occur. For example, the Tillamook Burn, a series of wildfires that occurred from 1939-1951, burned approximately 350,000 acres. Warming temperatures and changes in timing and patterns of precipitation due to climate change may increase fire frequency and severity in this ecoregion.

Some towns in Oregon’s Coast Range ecoregion include Astoria, Bandon, Brookings, Cannon Beach, Elkton, Florence, Gold Beach, Lincoln City, Newport, Tillamook, Waldport, and Yachats. The largest urban area on the coast is in Coos Bay/North Bend, which serves as a hub for fishing, shellfish, forest products, and transportation. Forestry remains the primary industry in the interior portion of the ecoregion. The Oregon coast offers excellent recreational opportunities, and tourism is important to local communities. Commercial and recreational fishing and fish processing are significant components of the economy. The Coast Range is a popular destination for retirees, so retirement services are important to coastal communities.

Characteristics

Important Industries

Forest products, agriculture, commercial fishing, fish processing, tourism and recreation, and retirement services

Major Crops

Livestock forage, timber, beef and dairy cattle

Important Nature-based Recreational Areas

Coos Bay, Tillamook Bay, Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area, Siuslaw National Forest, Clatsop and Tillamook State Forests, Elliot State Research Forest, Lower Rogue River, South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve, Cape Kiwanda, Jewell Meadows Wildlife Area, Coquille Valley Wildlife Area

Elevation

From 0 to 4,100 feet

Important Rivers

Alsea, Chetco, Clastskanie, Coos, Coquille, Illinois, Lewis and Clark, Necanicum, Nehalem, Nestucca, Rogue, Siletz, Siuslaw, Trask, Umpqua, Wilson, Yaquina, Youngs

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor:

Land Use Conversion and Urbanization

CMP Direct Threats 1, 2.1, 2.3, 7.2

Some areas of the Coast Range are developing rapidly, especially coastal communities, such as Cannon Beach, Lincoln City, and Newport. Steep slopes limit the amount of land available for development, and concentrate it in sensitive areas, particularly flatter lowlands and wetlands near rivers and estuaries. Residential development contributes to habitat loss and can contribute to loss of industry, such as agriculture and forestry. Historic draining of wetlands and marshes for agricultural use has also had significant impacts. Coastal rivers, wetlands, and estuaries were altered when side channels were diked, marshes drained, and channels deepened. These changes removed necessary habitat complexity, degraded water quality, and reduced estuarine habitat for fish and wildlife.

Recommended Approach

Work with community leaders and local governments to encourage planned, efficient growth. Support existing land use regulations to preserve farmland and forestland, open spaces, recreation areas, wildlife refuges, and natural habitats. Provide outreach about the benefits of wetland and tideland restoration. Support riparian buffers on all streams. Where possible, remove dikes and tide gates to restore estuarine habitats. Where tide gates need to be retained, replace older gates with side-hinged or aluminum gates that improve fish passage and hydrologic functions.

Limiting Factor:

Water

CMP Direct Threats 7.2, 11.4

Water Quantity is a limiting factor for fish and wildlife. Changing climate conditions are leading to rising temperatures and altered patterns of precipitation, which affect water availability across different times of year. Surface water is the primary source of drinking water for nearly all municipal and community water providers along the coast. Some water providers currently face water shortages, and future shortages are anticipated due to decreasing supplies and increasing demand, especially during peak tourism season.

Water Quality can also limit species and habitats. Runoff from agricultural and urban areas can contaminate waterways. Landscape-scale application of herbicides in industrial timber operations can also negatively impact water quality. Warming temperatures, combined with higher nutrient levels due to agricultural runoff, are increasing the prevalence of toxic algal blooms, leading to shellfish fishery closures and fish and wildlife mortality. Timber harvest on steep slopes without control measures and agricultural grazing practices in moist soils along the coast contribute to increased sedimentation in streams, wetlands, and estuaries, causing changes in plant community composition, reducing habitat complexity, and altering water circulation and nutrient flows.

Recommended Approach

Provide incentives and information about water usage and sharing during low flow conditions (e.g., late summer). Promote water management actions that enable climate resilience and adaptation. Invest in watershed-scale projects for cold water and flow protection. Identify and protect cold water rearing and refugia habitat for aquatic species. Increase awareness and manage timing of applications of potential aquatic contaminants. Improve compliance with water quality standards and pesticide use labels administered by the DEQ and EPA. Work on implementing Senate Bill 1010 (Oregon Department of Agriculture) and DEQ Total Maximum Daily Load

water quality plans.

Limiting Factor:

Habitat Fragmentation

CMP Direct Threats 1, 2.1, 2.3, 3.3, 8.1

Increasing traffic volumes, road density, recreational pressure, resource extraction, and aging water control structures contribute to habitat loss and fragmentation and create significant barriers to animal movements. In this ecoregion, US Highway 101 runs north to south, limiting connectivity between coastal dunes, estuaries, and other shoreline habitats to inland wetlands, grasslands, and forests. At the northern end of the Coast Range, US Highway 30 bisects the Columbia River floodplain marshes and upstream tidal rivers. While Oregon Forest Practices Act rules help to maintain some structural components and diversity on the landscape, commercial timber harvest can fragment forested habitats, reduce tree species diversity, and limit forest structural complexity. Many water control structures, such as culverts, are old and have not been well-maintained. These aging structures are often inundated with sediment and may be perched above water courses, preventing use by wildlife and blocking movement of fish. Older tide gates alter hydrologic functions, block fish passage, and reduce estuarine habitats.

Recommended Approach

Where possible, remove dikes and tide gates to restore estuarine habitats. Where tide gates need to be retained, replace older gates with new innovations, such as side-hinged and aluminum gates that improve fish passage and hydrologic functions.

Work with community leaders, agency partners, tribes, and forest managers to protect wildlife movement corridors and to fund and implement site-appropriate habitat enhancement and restoration efforts to facilitate wildlife movement. Promote the protection, restoration, and maintenance of Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas, following the guidelines outlined in Oregon’s Wildlife Corridor Action Plan. Work with the Oregon Department of Transportation and county and city transportation departments to improve wildlife passage across roadways and replace aging water control structures to improve hydrologic function and permit fish passage. Prioritize timber harvest practices that retain a diversity of tree and shrub species and habitat structural components, with variable density thinning to help retain connections between forested areas.

Preserve existing farmland while restoring ecological functions that have been lost or degraded, particularly in tidal lowlands. Provide incentives (e.g., financial assistance, conservation easements) and information about the benefits of maintaining fish and wildlife habitat. Broad-scale conservation strategies will need to focus on restoring and maintaining more natural ecosystem processes and functions within areas that are managed primarily for other values. This may include an emphasis on more “conservation-friendly” management techniques for existing land uses, and restoration of some key ecosystem components such as estuarine function.

Limiting Factor:

Invasive Species

CMP Direct Threat 8.1, 8.2

Non-native plant and animal invasions disrupt native communities, diminish populations of at-risk native species, and threaten the economic productivity of resource lands and waters. Invasive plants have increased substantially during the past several decades. In this ecoregion, Himalayan blackberry is widespread, with significant local impacts to meadows, riparian areas, and grasslands. Other invaders include reed canary grass, purple loosestrife, and yellow flag iris. Along the coast, European beach grass, introduced to stabilize shifting sands along roads, and gorse, introduced as an ornamental “living fence”, have substantial negative impacts. European beach grass alters dune formation and has narrowed beaches, drastically reducing open, sandy habitats that are critical to native species. Gorse crowds out native plants and chokes streams, reducing fish and wildlife habitat, and is also highly flammable, significantly increasing wildfire risk.

Invasive animals have also caused significant issues in the Coast Range. Non-native smallmouth bass have been illegally introduced to several areas in the ecoregion, including the Coquille Basin and Eel Lake, negatively impacting a variety of native fish species. American bullfrogs are rapidly expanding, competing with native species for limited resources or preying on native species and/or their eggs or young. Nutria degrade water quality and destabilize stream banks, while competing with native species, such as American beaver and muskrat, for food. Barred owls, expanding westward from their native range in the eastern US, compete directly with the native, threatened Northern spotted owl for food and habitat. Barred owls may also hybridize with spotted owls.

Emerging threats from invasive invertebrates are also becoming a concern in this ecoregion. The non-native emerald ash borer defoliates tree species characteristic of riparian habitats, such as Oregon ash, putting riparian areas, and in-stream habitats that depend on shading from bankside trees, at risk.

Recommended Approach

Emphasize prevention, risk assessment, early detection, and quick control to prevent new invasive species from becoming fully established. Prioritize management and control efforts to focus on key invasive species in high priority areas, particularly where Key Habitats and Species of Greatest Conservation Need occur. Where needed, use multiple site-appropriate tools (e.g., mechanical, chemical, and biological) to control the most damaging invasive species. Work with partners to implement measures to prevent unintentional introduction of non-native species (e.g., implement existing ballast water treatment regulations). Provide information to the public about the ecological and economic damage that invasive species cause. Work with the Oregon Invasive Species Council and other partners to educate people about invasive species issues and to prevent introductions of potentially high-impact species. Provide technical and financial assistance to landowners interested in controlling invasive species on their properties. Promote the use of native species for restoration and revegetation.

Limiting Factor:

Recreational Activity

CMP Direct Threats 1.3, 4.1, 5.1, 5.2, 5.4, 6.1

Activities like hiking, biking, hunting, fishing, camping, jet boating, foraging, unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), and off-road vehicle use can create sensory stressors for wildlife, with sound, light, and unusual smells that may disrupt behavior and deter species from moving through certain areas. Recreation contributes positively to the Coast Range’s economy and local communities and is managed carefully in many areas. However, increasing numbers of recreationists can impact sensitive areas, such as shorebird nesting areas, tidepool habitats, and haul out sites for marine mammals. There are concerns with off-leash dogs in some areas. Off-highway vehicle use and target shooting are increasing on public forestlands, especially in areas near cities. In many areas, off-highway vehicle and mountain bike use is not closely managed, leading to habitat destruction as users create new networks of unsanctioned, unregulated trails. Dispersed recreation can cause new roads and trails to fragment the landscape and can cause the spread of invasive species from other locations. As inland areas experience more very hot days and more lands in inland ecoregions are closed to the public due to wildfire, public lands in the Coast Range are experiencing greater use.

Recommended Approach

Work with state and federal forest management agencies to plan recreational use and to increase education and outreach for recreationists and associated businesses. Work with land management agencies such as the USFS to designate areas as high value recreation and low habitat impact areas. Institute road and/or area closures to protect species during sensitive times of year and decommission roads when possible. Monitor to ensure that OHV rules for use and public lands motor vehicle use maps are enforced by the managing agencies. Improve public awareness of sensitive areas through signage and kiosks. Follow guidelines for responsible recreation, such as Leave No Trace, to minimize impacts.

Limiting Factor:

Oil Spills

CMP Direct Threats 4.1, 4.3, 9.2

Oil spills along the coast can have devastating effects on coastal habitats, fish, shellfish, and wildlife. Tidal flux can spread oil or other hazardous materials around sensitive habitats very quickly. Rapid response in the event of a spill is essential. Additionally, spills of hazardous materials or oil from vehicles traveling on roads along the coast could potentially impact nearby rivers, wetlands, estuaries, fish, and aquatic wildlife.

Recommended Approach

Ensure rapid response and preparedness for spills of hazardous substances. Oregon Department of Environmental Quality’s (DEQ) Marine Oil Spill Prevention Program and the Pacific States/British Columbia Oil Spill Task Force work with multiple parties and interested partners to address these concerns and quickly identify appropriate actions.

Strategy Species

Black Brant

Branta bernicla nigricans

Black Petaltail

Tanypteryx hageni

California Mountain Kingsnake

Lampropeltis zonata

California Myotis

Myotis californicus

Cascade Head Catchfly

Silene douglasii var. oraria

Caspian Tern

Hydroprogne caspia

Chum Salmon, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus keta

Chum Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus keta

Clouded Salamander

Aneides ferreus

Coast Range Fawn Lily

Erythronium elegans

Coastal Cutthroat Trout

Oncorhynchus clarki clarki

Coastal Tailed Frog

Ascaphus truei

Coho Salmon, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Coho Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Coho Salmon, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Columbia Torrent Salamander

Rhyacotriton kezeri

Columbian White-tailed Deer

Odocoileus virginianus leucurus

Cope’s Giant Salamander

Dicamptodon copei

Del Norte Salamander

Plethodon elongatus

Eulachon

Thaleichthys pacificus

Fall Chinook Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Fisher

Pekania pennanti

Foothill Yellow-legged Frog

Rana boylii

Fringed Myotis

Myotis thysanodes

Green Sturgeon, Northern DPS

Acipenser medirostris

Green Sturgeon, Southern DPS

Acipenser medirostris

Harlequin Duck

Histrionicus histrionicus

Hoary Bat

Lasiurus cinereus

Hoary Elfin Butterfly

Incisalia polia maritima

Insular Blue Butterfly

Plebejus saepiolus littoralis

Long-legged Myotis

Myotis volans

Marbled Murrelet

Brachyramphus marmoratus

Millicoma Dace

Rhinichthys cataractae ssp

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

Nelson’s Checkermallow

Sidalcea nelsoniana

Northern Red-legged Frog

Rana aurora

Northern Spotted Owl

Strix occidentalis caurina

Northwestern Pond Turtle

Actinemys marmorata

Olive-sided Flycatcher

Contopus cooperi

Oregon Silverspot Butterfly

Speyeria zerene hippolyta

Pacific Lamprey

Entosphenus tridentatus

Pacific Marten

Martes caurina

Pacific Walker

Pomatiopsis californica

Peregrine Falcon

Falco peregrinus anatum

Pink Sandverbena

Abronia umbellata var. breviflora

Point Reyes Bird’s-beak

Cordylanthus maritimus ssp. palustris

Purple Martin

Progne subis arboricola

Red Tree Vole

Arborimus longicaudus

Ringtail

Bassariscus astutus

Robust Walker

Pomatiopsis binneyi

Silver-haired Bat

Lasionycteris noctivagans

Silvery Phacelia

Phacelia argentea

Sisters Hesperian

Hochbergellus hirsutus

Southern Torrent Salamander

Rhyacotriton variegatus

Spring Chinook Salmon, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Summer Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Summer Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Summer Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat

Corynorhinus townsendii

Tufted Puffin

Fratercula cirrhata

Umpqua Chub

Oregonichthys kalawatseti

Western Brook Lamprey

Lampetra richardsoni

Western Bumble Bee

Bombus occidentalis

Western Lily

Lilium occidentale

Western Painted Turtle

Chrysemys picta bellii

Western Ridged Mussel

Gonidea angulata

Western River Lamprey

Lampetra ayresii

Western Snowy Plover

Charadrius nivosus nivosus

Western Toad

Anaxyrus boreas

White Sturgeon

Acipenser transmontanus

Winter Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Wolf’s Evening Primrose

Oenothera wolfii

Conservation Opportunity Areas

Alsea Estuary-Alsea River [COA ID: 029]

The Alsea Estuary is large and shallow and provides overwintering habitat for migrating waterfowl and rearing habitat for coastal salmonids. The COA also has had extensive salt marsh habitat restoration and contains a lot of public lands.

Beaver Creek [COA ID: 027]

Beaver creek watershed is diverse and productive as habitats start at the beach and move up to the old growth forests.

Cape Ferrelo [COA ID: 051]

This area includes unique rocky intertidal habitat, important shorebird habitat, and coastal bluffs.

Chetco River-Winhchuck River Estuaries [COA ID: 052]

This diverse area includes habitats ranging from coastal dunes and estuaries to mature upland conifer forests.

Clatskanie River [COA ID: 008]

The area connects with Columbia – Clatskanie COA and contains the entire Clatskanie River watershed. OWEB has granted Lower Columbia Watershed Council and others to reconnect Westport Slough to the Clatskanie River.

Clatsop Plains [COA ID: 001]

This area which is about 30 square miles, is composed of Gearhart Fen the largest contiguous wetland of its kind remaining on the Oregon coast. The Clatsop Plains beaches provide habitat for shorebirds during migration (e.g. Sanderlings) and potential areas for nesting Western Snowy Plovers. The area is conterminal with Necanicum River, Tillamook Head and …

Clatsop State Forest-Jewel Meadows Area [COA ID: 007]

The area includes Clatsop State Forest and Jewel Meadows Wildlife Area and connects with Columbia River – Blind Slough Swamp. The watershed provides critical habitat for many coastal plant and animal communities. The area contains managed forest including components of mature stands and remnant large trees and open upland grassland meadows.

Columbia River-Blind Slough Swamp [COA ID: 006]

This is a an extensive area on the lower Columbia River Estuary from east of Tongue Point upstream to Crims Island. The area encompasses the Julia B. Hanson and Lewis and Clark National Wildlife Refuges and the Blind Slough Swamp Preserve, which contains ancient Sitka spruce trees and is one of the best examples of swamps …

Coos Bay [COA ID: 043]

Encompasses Coos Bay and surrounding habitats. Includes the towns of Coos Bay and North Bend.

Coos Mountain-Middle Creek [COA ID: 044]

Connecting to the Lower Coquille River COA, this area follows Middle Creek northward and includes surrounding riparian and upland habitat

Deer Island [COA ID: 053]

A large (3,000+ acres) island located at River Mile 78-81 along the Lower Columbia River.

Depoe Bay Area [COA ID: 023]

The Depoe Bay COA contains the world’s smallest harbor and has a productive rocky shore and headlands for fish and wildlife use.

Devil’s Lake [COA ID: 020]

Rock Creek which flows into Devil’s Lake is one of the most important Coho producing streams on the coast. Rock Creek mouth is a peat marsh of several acres in size.

Elliot State Forest [COA ID: 041]

Located immediately adjacent to Tenmile Lakes COA, this area is located inland east from the town of Lakeside. Bounded by Highway 38 and the Umpqua River to the north.

Forest Park [COA ID: 058]

This area in the Tualatin Mountains (Portland’s West Hills) includes the City of Portland’s 5,172-acre Forest Park.

Gales Creek [COA ID: 013]

The area is a late successional mixed deciduous and conifer forest with wetlands, flowing water and riparian habitats in the Gales Creek watershed. The 46 square mile area is conterminal with Nehalem and Salmonberry River Headwaters and Tillamook Bay and Tributaries COAs.

Heceta Head [COA ID: 031]

A coastal headland with nearby steller sea lion haulouts. A large portion of the Siuslaw National Forest is included.

Kalmiopsis Area [COA ID: 100]

This areas borders the western edge of the Kalmiopsis Wilderness and has unique plant communities due to the serpentine soils endemic to the Klamath Mountains ecoregion.

Kings Valley-Woods Creek Oak Woodlands [COA ID: 080]

This corridor in Benton County extends from the south end of Woods Creek Rd. through the town of Wren, along Kings Valley Highway, to the Polk County line

Lower Coquille River [COA ID: 045]

Follows the Lower Coquille River from its mouth at the Oregon coast and extending east to Highway 42 (past the Benham Airport)

Lower Rogue River and Estuary [COA ID: 049]

This are contains the mouth of the Rogue River and is important habitat for Salmonids accessing the rest of the system. It has mature upland forests with a productive hardwood understory that supports a diverse assemblage of wildlife species.

Lower Willamette River Floodplain [COA ID: 059]

The Willamette River mainstem from the confluence with the Columbia River (RM 0) upstream to Willamette Falls in Oregon City (RM26), its floodplain and adjacent uplands.

Luckiamute River and Tributaries [COA ID: 075]

The Luckiamute and Little Luckiamute Rivers and tributary drainages and associated agricultural lands surrounding the Kings Valley Area and South of Falls City.

Mary’s Peak [COA ID: 028]

Covers Mary’s Peak and surrounding wilderness area. Located north of Highway 34 and southwest of Philomath.

McTimmons Valley – Airlie Savanna [COA ID: 076]

Twelve square miles of grassland and oak savanna habitat surrounding McTimmonds Creek, north of Pedee

Mill Creek [COA ID: 024]

Relatively small (15 sq mi) COA at the eastern edge of the Coast Range ecoregion, building from the Red Prairie-Mill Creek – Willamina Oaks COA in the Willamette Valley ecoregion, northwest of the town of Dallas.

Necanicum Estuary [COA ID: 002]

Necanicum is designated as a conservation estuary. The City of Seaside and the North Coast Land Conservancy have acquired a network of tidal wetlands along Neawanna Creek estuary that are designated as a natural history park.

Necanicum River [COA ID: 004]

The area includes much of the Necanicum River. The watershed provides critical habitat for many coastal plant and animal communities. Floodplains and associated wetland and riparian ecosystems provide important flood protection for downstream communities and act as corridors allowing wildlife to move along and between habitat areas. Management of the area promotes the connectivity and …

Nehalem and Salmonberry River Headwaters [COA ID: 012]

The area is a late successional mixed conifer forest with flowing water and riparian habitats in the Nestucca watershed. It is conterminal with Tillamook Bay and Tributaries COA. The area includes much of the watershed of the North Fork Nehalem River.

Nehalem River Estuary [COA ID: 009]

The area includes the Nehalem River watershed from the ocean/estuary close to the headwaters by connection with the North Fork Nehalem COA . The area includes Nehalem Bay State Park. The state park helps to protect the 4-mile north spit from development. In April 2015 Western Snowy Plovers were found attempting to nest at Nehalem …

Nestucca Bay [COA ID: 016]

This area is conterminal with Sand Lake, and Salmon River – Cascade COAs. The area includes Nestucca Bay National Wildlife Refuge, at 1,202 acres, is the largest refuge within the Oregon Coastal Refuge Complex. The refuge also includes Neskowin Marsh, Little Nestucca River Unit, Martella Tract and Two Rivers Peninsula. Neskowin Marsh Unit protects a …

Nestucca River Watershed [COA ID: 017]

A 190 square mile area of coast range mixed and late successional conifer forest, riparian areas of Nestucca River, and freshwater wetlands. Area is conterminal with Nestucca Bay and Trask Mountain COA.

Netarts Bay [COA ID: 014]

This area is conterminal with Sand Lake, Tillamook Bay COAs. The Bay is over 2,300 acres in size and is Oregon’s seventh largest coastal bay. It is bounded on the west by an extensive sand bar/spit. The bay is important for migratory and wintering shorebirds and waterfowl and marine mammals. Historical nesting site for Western …

New River Area [COA ID: 047]

Located on the Oregon Coast, bounded by Cape Blanco Airport to the south and Bandon to the north.

North Fork Nehalem River [COA ID: 010]

The area includes the upper Nehalem River watershed to the headwaters. The area is connected to Nehalem River Estuary Nehalem COA River Estuary. It is identified by the Oregon Plan as important for native salmonids.

North Fork Siuslaw River [COA ID: 032]

A low elevation gradient river meanders to the mainstem Siuslaw river with a mixture of salt and freshwater wetlands

North Fork Smith River [COA ID: 037]

Includes a significant portion of the North Fork Smith River and surrounding upland and riparian habitat, including portions of Siuslaw National Forest

Pistol River Estuary [COA ID: 050]

This area contains the Pistol River Estuary, offshore rocky habitat for nesting seabirds, and Coastal Bluffs.

Red Prairie-Mill Creek-Willamina Oaks South [COA ID: 071]

Area is located south of Highway 19 along Highway 22 in the foothills of the Coast Range Mountains. Includes tributaries of South Yamhill River and associated lowland habitats.

Rickreall Creek and Little Luckiamute River Headwaters [COA ID: 025]

Relatively small, stand-alone COA at the border of the Coast Range ecoregion with the Willamette, just west of Falls City.

Rogue River [COA ID: 093]

This area contains habitat along the mainstem of the Rogue River including portions of the Wild and Scenic area.

Saddle Mountain [COA ID: 005]

The area contains the 3,226 acre Saddle Mountain State Park and state Natural Area, which contains the tallest mountain in Clatsop County (3,283′). Area connects with the Necanicum River watershed. Saddle Mountain is one of eight state natural areas dedicated on state managed lands.

Salmon River Estuary-Cascade Head [COA ID: 019]

This conservation opportunity area provides a unique combination of habitat types, from the rocky shoreline inland and includes the Cascade Head Scenic Research Area. At least 3 threatened and endangered species exist here including the Oregon Silverspot butterfly.

Sand Lake Area [COA ID: 015]

Relatively small (19 sq mi) area on the Oregon coast just north of Pacific City.

Sauvie Island-Scappoose [COA ID: 054]

This area is located north of Portland and is comprised of Sauvie Island, Multnomah Channel, the Scappoose Bay area and the eastern most slopes of Forest Park along Highway 30.

Scoggins Valley-Mount Richmond [COA ID: 063]

Area is located in the foothills of the Coast Range Mountains and includes the Upper Tualatin-Scoggins Watershed, portions of the North Yamhill River and headwater tributaries, Mount Richmond, and the Oak Ridge / Moore’s Valley area.

Siletz Bay [COA ID: 021]

The Siletz estuary is a diverse and complex habitat system, occupied by numerous fish and wildlife species.

Siletz River [COA ID: 022]

This Siletz River COA is a sandstone/basalt river system with variable flashy winter river flows. The surrounding forest are primarily private owned and are actively managed for wood production.

Siuslaw River [COA ID: 035]

This COA stretches many miles from tidally influenced to the Willamette Valley and represents may strategy habitats.

Siuslaw River Estuary [COA ID: 034]

A rather small bay for the size of the river the COA is low elevation and low gradient with many islands and salt/freshwater marshes

Sixes River-Elk River [COA ID: 048]

This area contains much of the Coast Range’s Oak Woodlands and is potential habitat for Western Snowy Plover. It is a key corridor for migrating birds and has high plant and animal diversity.

South Fork Coquille [COA ID: 046]

Relatively large (222 sq mi) area located within the Coast Range near the Rogue River-Siskiyou Forest and immediately adjacent to the Sixes River-Elk River COA

Sutton Lake Area [COA ID: 033]

Sea Level coastal lakes with limited tidal influence and large enough to have cold water and waves

Tahkenitch-Siltcoos Lakes [COA ID: 036]

Two large coastal lakes with floating peat islands and large numbers of wintering waterfowl exist in this COA. Carnivorous pitcher plants (Darlingtonia are found along the edges.

Tenmile Lake [COA ID: 040]

On the Oregon Coast near the town of Lakeside, includes North and South Tenmile Lake and surrounding habitat

Tillamook Bay and Tributaries [COA ID: 011]

A large bay some 6 miles long with five rivers flowing in to it. Extensive sand/mudflats provide habitat for migratory and breeding waterfowl and shorebirds. The bay is protected from the open ocean by a the Bayocean Spit, formerly used by nesting Western Snowy Plovers.

Tillamook Head [COA ID: 003]

This area includes Ecola State Park and surrounding 9 miles of coastline between Seaside and Cannon Beach. The area includes coastal Sitka spruce forest, eventually opening up to a grassy bluff. Sea stacks punctuate the long sweep of shoreline to the south. Offshore islands provide nesting and loafing areas for several species of seabirds.

Trask Mountain [COA ID: 018]

A 37 square mile area of coast range mixed and late successional conifer forest and riparian areas of North Yamhill River wetlands. Area is conterminal with Nestucca River Watershed and Scoggins Valley-Mount Richmond COAs.

Umpqua River [COA ID: 042]

Area follows the windy Umpqua River and surrounding riparian and upland habitat. Bounded at the north by Elkton and at the south near the towns of Melrose and Winchester

Umpqua River Estuary [COA ID: 038]

Area focuses on the Umpqua River Estuary, bounded by the coastline to the west and Highway 38 to the east

Upper Siuslaw [COA ID: 089]

Follows the windy Siuslaw River and surrounding habitat. Area builds from the Siuslaw Estuary COA to the west and extends east towards Cottage Grove.

Wassen Creek [COA ID: 039]

Connects to the northern portion of Umpqua River Estuary. Focuses on Wassen Creek and surrounding upland and riparian habitats. Includes some Siuslaw National Forest land

West Eugene Area [COA ID: 086]

This site extends from Camas Swale north along the foothills to Cox Butte, including the West Eugene wetlands

Yachats River Area [COA ID: 030]

A narrow river channel with a wide shallow mouth at the ocean, this COA incorporates steep coastal mountains.

Yamhill Oaks-Willamina Oaks North [COA ID: 067]

Area is located west of McMinnville in the foothills of the Coast Range Mountains and within the South Yamhill River Watershed.

Yaquina Bay [COA ID: 026]

The Yaquina estuary COA is a large watershed with numerous fish, wildlife, habitat, and human resources.