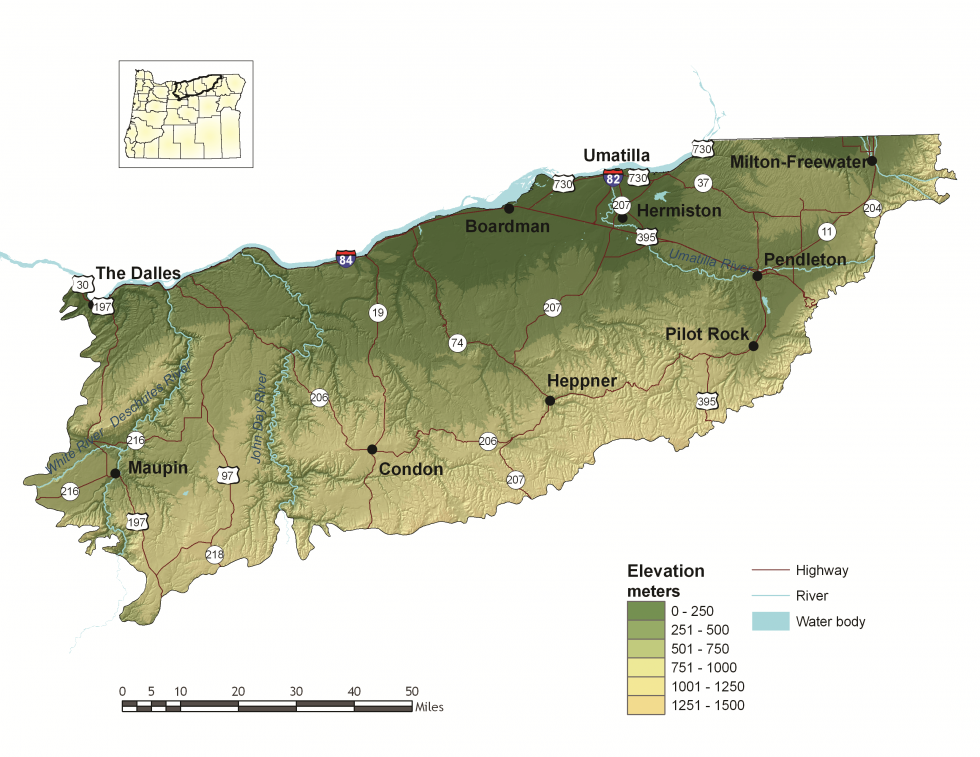

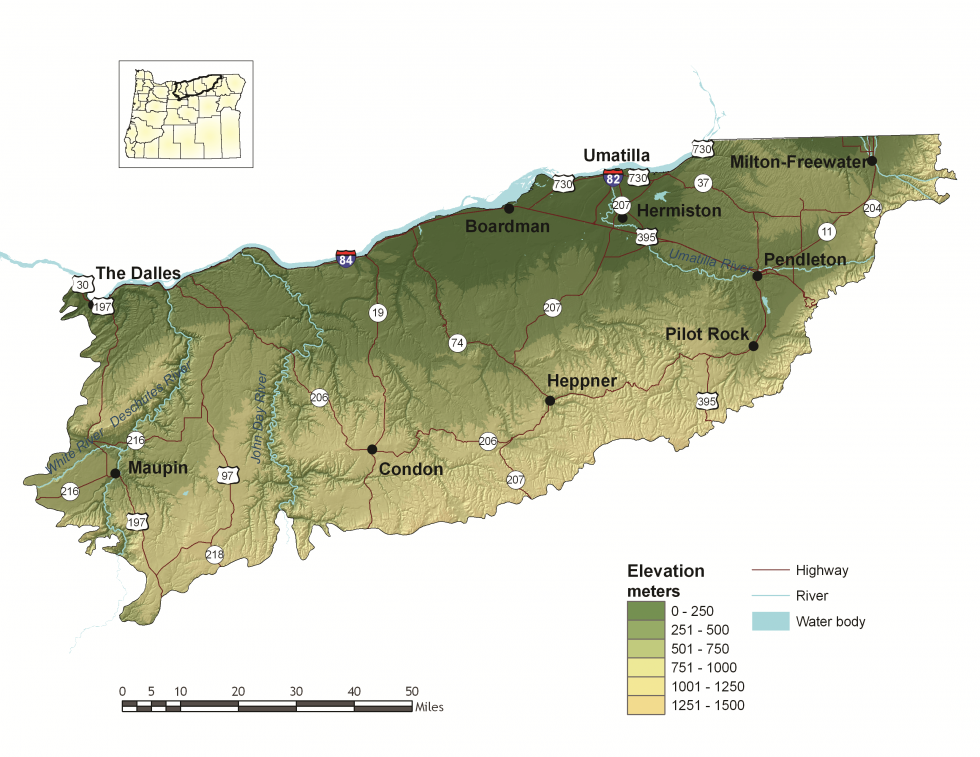

Description

The Oregon portion of the Columbia Plateau ecoregion extends from the eastern slopes of the Cascade Mountains to the border of the Blue Mountains ecoregion. The Columbia River delineates the northern border of the ecoregion in Oregon and has greatly influenced the surrounding area with cataclysmic floods and large deposits of wind-borne silt and sand. Over time, winds scoured the floodplain, depositing silt and sand across the landscape and creating ideal conditions for agriculture: rolling lands, deep soil, and plentiful flowing rivers. The ecoregion is made up of lowlands, with an arid climate, cool winters, and hot summers.

The Columbia Plateau ecoregion is characterized by sagebrush steppe and grassland habitats with extensive areas of dryland farming and irrigated agriculture. The Columbia Plateau produces the vast majority of Oregon’s grain, and grain production is the heart of the agricultural economy. The Columbia Plateau is second only to the Willamette Valley for agricultural production in Oregon. More than 80 percent of the ecoregion’s population and employment is located in Umatilla County, which includes the cities of Pendleton and Hermiston. Other population centers include The Dalles, Condon, and Heppner. Most of the Umatilla Indian Reservation is found in the Columbia Plateau ecoregion.

Characteristics

Important Industries

Agriculture, food processing, energy (solar and wind), livestock, retail and services, construction, recreation

Major Crops

Grain, barley, potatoes, onions, fruit

Important Nature-based Recreational Areas

Cold Springs National Wildlife Refuge (NWR), Umatilla NWR, the canyons of the lower Deschutes and John Day Rivers, Lower Deschutes Wildlife Area, Willow Creek Wildlife Area, Irrigon Wildlife Area, Coyote Springs Wildlife Area, Power City Wildlife Area

Elevation

100 feet (The Dalles) to over 4,000 feet along the southern border

Important Rivers

Columbia, Deschutes, John Day, Umatilla, Walla Walla

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor:

Water

CMP Direct Threats 7.2, 9.3, 11.4

Water Quantity is a limiting factor for fish and wildlife. Changing climate conditions are leading to rising temperatures and altered patterns of precipitation, which affects water availability across different times of year. In streams, seasonal low flows can limit habitat suitability and reproductive success for many fish and wildlife species. Reduced water availability for plants can affect the quality and availability of forage for many terrestrial species. In areas where urbanization is increasing, the demand for water is contributing to a decrease in the supply of groundwater. This reduces groundwater discharge of cold water to rivers and streams, subsequently reducing the availability of both cold water refugia and suitable habitat for cold-water dependent species. Many communities in the Columbia Plateau ecoregion are reliant on aquifers for water, and agricultural irrigation and private interests, such as aquifer use to cool computers in data centers, may threaten local water supplies. There are seven critical groundwater areas in Oregon, five of which are within the Columbia Plateau.

Water quality can also limit species and habitats. Runoff from agricultural areas can contaminate waterways. Warming temperatures, combined with higher nutrient levels due to agricultural runoff, are increasing the prevalence of harmful algal blooms in waterways like the lower John Day and Deschutes Rivers. These harmful algal blooms can cause large-scale fish die-off, sicken or kill wildlife, impact drinking water, and reduce habitat for fish and wildlife by blocking sunlight and creating hypoxic zones, also known as dead zones.

Recommended Approach

Provide incentives and information about water usage and sharing during low flow conditions (e.g., late summer). Promote water management actions that enable climate resilience and adaptation. Invest in watershed-scale projects for cold water and flow protection. Identify and protect cold water rearing and refugia habitat for aquatic species. Increase awareness and manage timing of applications of potential aquatic contaminants. Improve compliance with water quality standards and pesticide use labels administered by the DEQ and EPA. Work on implementing Senate Bill 1010 (Oregon Department of Agriculture) and DEQ Total Maximum Daily Load water quality plans.

Limiting Factor:

Habitat Fragmentation

CMP Direct Threats 2.1, 2.3, 3.3, 8.1

The impact of human activity in the Columbia Plateau is high. The majority of the prairie and shrub-steppe habitat has been converted for agricultural uses. The remaining Key Habitats for at-risk native plant and animal species are limited and largely confined to small and often isolated fragments, such as roadsides and sloughs. These remaining parcels have the potential to be converted to agriculture, and there are few opportunities for large-scale protection or restoration of native landscapes. Existing land use and land ownership patterns present challenges to large-scale ecosystem restoration.

Recommended Approach

Provide incentives (e.g., financial assistance, conservation easements) and information about the benefits of maintaining bird and other wildlife habitat. Broad-scale conservation strategies will need to focus on restoring and maintaining more natural ecosystem processes and functions within a landscape that is managed primarily for other values. This may include an emphasis on more “conservation-friendly” management techniques for existing land uses, and restoration of some key ecosystem components such as riparian function. “Fine filter” conservation strategies that focus on needs of individual Species of Greatest Conservation Need and key sites are particularly important in this ecoregion.

Because approximately 84 percent of the Columbia Plateau ecoregion is privately-owned, voluntary cooperative approaches are the key to long-term conservation using tools such as financial incentives, regulatory assurance agreements, and conservation easements. Where appropriate, plan development carefully to maintain existing native habitats. Identifying important habitat areas and directing mitigation from ongoing energy development may be another protection strategy. Promote the protection, restoration, and maintenance of Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas, following the guidelines outlined in Oregon’s Wildlife Corridor Action Plan.

Limiting Factor:

Invasive Species

CMP Direct Threat 8.1

Invasive plant and animal species disrupt native communities, diminish populations of at-risk native species, and threaten the economic productivity of resource lands including farmland and rangeland. Differences in county policies and funding availability regarding invasive species have resulted in some inconsistencies in approach. Non-native annual grasses, such as cheatgrass and medusahead, have rapidly expanded in perennial grass systems in the Columbia Plateau, displacing desirable forage for wildlife and livestock. Invasion of cheatgrass has also increased fuel loads substantially, leading to catastrophic fire events. Invasive species such as yellow star thistle, Russian thistle, and Russian olive are also of concern, growing rapidly to crowd out native species.

Recommended Approach

Emphasize prevention, risk assessment, early detection, and quick control to prevent new invasive species from becoming fully established. Use multiple site-appropriate tools (e.g., mechanical, chemical and biological) to control the most damaging invasive species. Focus on key invasive species in high priority areas, particularly where Key Habitats and Species of Greatest Conservation Need occur. Ensure cooperation and collaboration between counties, landowners, land managers, and other entities with invasive species policies and interests. Promote the use of native species for restoration and revegetation.

Limiting Factor:

Energy Development

CMP Direct Threat 3.3

Climate change and global economies are increasing pressure for renewable energy development, including wind, solar, and geothermal energy. Energy projects offer environmental benefits but also have impacts on fish, wildlife, and their habitats. Wind energy potential is especially high in the Columbia Plateau. The area is increasingly challenged with the need to balance the state’s interest in clean energy development with local natural resource conservation needs.

Recommended Approach

Plan energy projects carefully, using the best available information and consultation with biologists. See the Key Conservation Issue on Land Use Changes, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Solar Sitting Guidance and the Oregon Columbia Plateau Ecoregion Wind Energy Sitting and Permitting Guidelines. Focus potential mitigation efforts from energy siting into areas of greatest habitat integrity in the region. Avoid siting new facilities within critical movement and migration areas, including Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas.

Limiting Factor:

Soil Erosion

CMP Direct Threats 2.1, 9.3, 9.5

Soil loss through erosion and decreases in soil quality jeopardize the productivity of native habitats and agricultural lands. Agricultural use, particularly tilled production without the use of cover crops, is prevalent in the Columbia Plateau ecoregion. This region also sees characteristically high, sustained winds, contributing to soil loss. Sandy soils along the Columbia River are particularly susceptible to erosion from high winds. Soil erosion decreases water infiltration, which is essential for productive habitats and groundwater recharge, and can also increase sediment loading in streams, as well as air-borne pollutants.

Recommended Approach

Use incentives to promote no-till farming and agricultural practices that do not allow land to lay bare for long periods of time. Support no-till practices that use crop rotation and cover crops. Encourage participation and support for programs such as the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Conservation Reserve Program, which promote practices that can offset or minimize soil erosion and degradation.

Strategy Species

Brewer’s Sparrow

Spizella breweri breweri

Bulb Juga

Juga bulbosa

Bull Trout, John Day SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Umatilla SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Burrowing Owl

Athene cunicularia hypugaea

California Mountain Kingsnake

Lampropeltis zonata

Common Nighthawk

Chordeiles minor

Dalles Mountainsnail

Oreohelix variabilis variabilis

Fall Chinook Salmon, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Ferruginous Hawk

Buteo regalis

Grasshopper Sparrow

Ammodramus savannarum perpallidus

Hoary Bat

Lasiurus cinereus

Lawrence’s Milkvetch

Astragalus collinus var. laurentii

Lewis’s Woodpecker

Melanerpes lewis

Loggerhead Shrike

Lanius ludovicianus

Long-billed Curlew

Numenius americanus

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

Northern Sagebrush Lizard

Sceloporus graciosus graciosus

Northern Wormwood

Artemisia campestris var. wormskioldii

Pacific Lamprey

Entosphenus tridentatus

Pallid Bat

Antrozous pallidus

Purple-lipped Juga

Juga hemphilli maupinensis

Sagebrush Sparrow

Artemisiospiza nevadensis

Shortface Lanx

Fisherola nuttalli

Silver-haired Bat

Lasionycteris noctivagans

Spotted Bat

Euderma maculatum

Spring Chinook Salmon, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Summer Steelhead / Columbia Basin Redband Trout, Mid Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss gairdneri

Swainson’s Hawk

Buteo swainsoni

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat

Corynorhinus townsendii

Tygh Valley Milkvetch

Astragalus tyghensis

Washington Ground Squirrel

Urocitellus washingtoni

Western Brook Lamprey

Lampetra richardsoni

Western Bumble Bee

Bombus occidentalis

Western Painted Turtle

Chrysemys picta bellii

Western River Lamprey

Lampetra ayresii

Westslope Cutthroat Trout

Oncorhynchus clarki lewisi

Conservation Opportunity Areas

Bakeoven Creek-Buckhollow Creek [COA ID: 151]

The northern boundary of this COA follows Buck Hollow Creek, with the remaining boundaries connecting to the Lower Deschutes River (COA ID 148) and Lawrence Grasslands (COA ID 152) COAs.

Boardman Area [COA ID: 154]

South of the Columbia River, in north central Oregon. Area includes important conservation lands near the Boardman Conservation Area; Willow Creek Wildlife Area; and grassland included in The Nature Conservancy conservation portfolio

Cold Springs National Wildlife Refuge Area [COA ID: 156]

Just east of Hermiston and extending to include a small stretch of the Columbia River. Includes Cold Springs National Wildlife Refuge

Deschutes River [COA ID: 149]

Mainly located on the Warms Springs Reservation, this narrow COA includes a section of the Deschutes River from above the confluence with the Warms Springs River, north to approximately 1.5 miles below White Horse Rapids. From east to west the COA runs from the east side of the Deschutes River, adjacent to White Horse rapids, …

Fifteenmile Creek [COA ID: 147]

Area just east of The Dalles Airport, following Fifteen Mile Creek, and extending north to the Oregon/Washington border along the Columbia River.

Lawrence Grasslands [COA ID: 152]

In the southwest corner of the ecoregion just west of Antelope.

Lower Deschutes River [COA ID: 148]

Follows the Lower Deschutes River Corridor and includes surrounding habitat.

Lower John Day River [COA ID: 153]

Area follows the lower John Day River and surrounding habitats.

Metolius Bench-Mutton Mountains Wildlife Movement Corridor [COA ID: 150]

This long narrow COA spans two ecoregions. Within the East Cascades, it begins on the south side of the Metolius River, northwest of Lake Billy Chinook, and crosses over the river and into the Warm Springs Reservation. Heading north east, the COA crosses into the Blue Mountains ecoregion, across US Highway 26, and at its …

Rock Creek-Butter Creek Grasslands [COA ID: 155]

This is the largest COA within the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion extending from Rock Creek to Butter Creek, totaling 809 square miles.

Walla Walla Headwaters [COA ID: 157]

This COA is mainly located within the Blue Mountains ecoregion of Umatilla, Union, and Wallowa Counties, but enters into a small section of the Columbia Plateau ecoregion along its northwest corner. Characterized by extensive mixed conifer forest, this rugged landscape also contains important native perennial grasslands, abundant springs, and abuts the North Fork Umatilla Wilderness …

Wasco Oaks [COA ID: 125]

Area extends from the Columbia River up through the Mt. Hood National Forest and has served as an important emphasis for conservation and restoration efforts.