Description

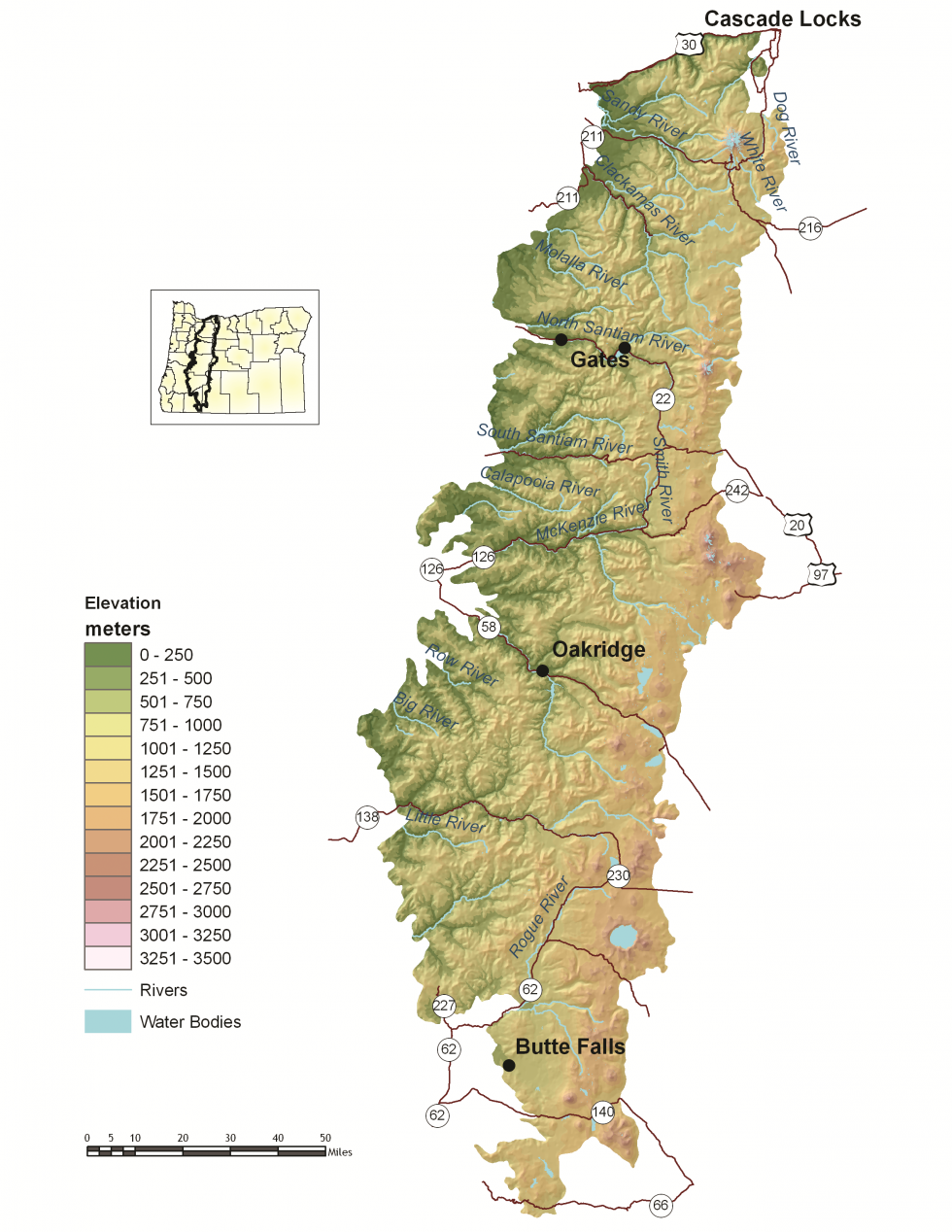

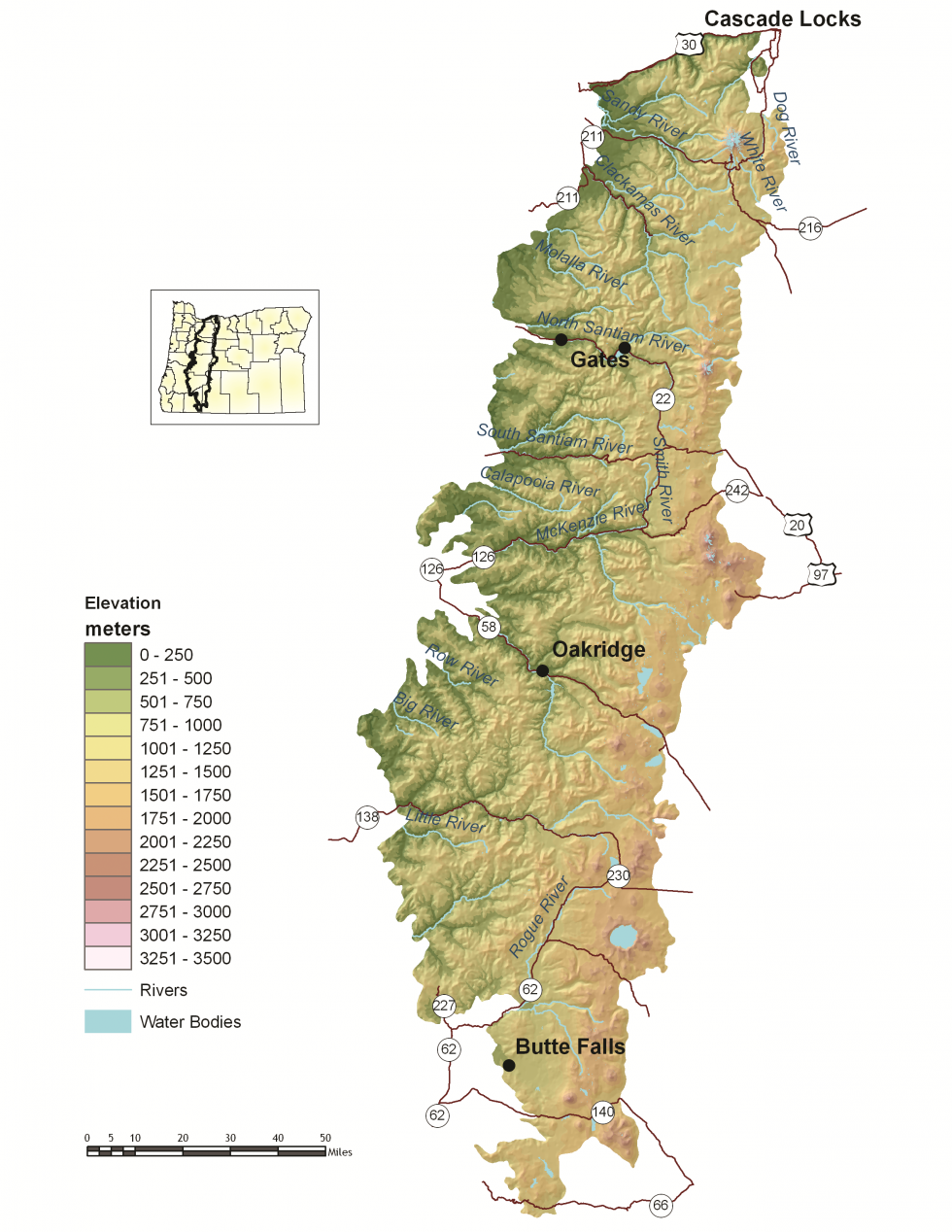

The West Cascades ecoregion extends from just east of the Cascade Mountains’ summit to the foothills of the Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue Valleys, and spans nearly the entire length of the state of Oregon, from the Columbia River to within five miles of the California border. The topography and soils of the West Cascades ecoregion have been shaped dramatically by its volcanic past. The West Cascades ecoregion has two geologically distinct areas: the younger volcanic crest (approximately 8 million years old) and the “old Cascades” to the west of the crest (at least 30 million years old). The volcanic crest includes the highest peaks in Oregon: Mt. Hood, Mt. Jefferson, and North, Middle, and South Sisters, all more than 10,000 feet. The “old Cascades” are characterized by long, steep ridges and wide, glaciated valleys.

This ecoregion is almost entirely forested by conifers, although the dominant tree species vary by elevation, site characteristics, and stand history. Douglas-fir is the most common tree below 4,000 feet, often with western hemlock as a co-dominant species. At higher elevations, dominant tree species include Pacific silver fir, mountain hemlock, or subalpine fir. Other common conifers include western redcedar, grand fir, and noble fir. Above approximately 7,000 feet, the conditions are too severe for tree growth, and alpine parklands and dwarf shrubs predominate, including some wetlands and barren expanses of rock and ice. In the southern areas, ponderosa pine, sugar pine, and incense cedar often are found with Douglas-fir at the lower elevations.

The climate and resulting fire regimes vary with latitude and elevation. The northern portion of the ecoregion is typified by less frequent but more severe fires, whereas the southern portion is typically drier with moderately frequent, mixed-severity, lightning-caused fires. Across the entire region, fire frequency and severity are increasing due to changing climate. At lower elevations, winter conditions are often mild with high rainfall. In contrast, above 4,000 feet, winters are typified by lower temperatures and much of the precipitation occurs as snowfall.

The West Cascades ecoregion is sparsely populated, with towns including Cascade Locks, Butte Falls, Detroit, Gates, Idanha, McKenzie Bridge, Blue River, Oakridge, Westfir, and part of Sandy and Sweet Home (the remainder of which lie in the Willamette Valley ecoregion). Local economies were once entirely dependent on timber harvest but have been greatly affected as market conditions (long-term and broad-scale changes in the forest products marketplace) and shifts in public forest management priorities have shaped Oregon’s timber industry. Many towns are increasingly promoting recreational opportunities, including hiking, camping, fishing, hunting, birding, mountain biking, and skiing.

Characteristics

Important Industries

Forest products, recreation (hiking, biking, wildlife viewing, hunting, fishing, snow sports)

Major Crops

Fruits, mint, cattle

Important Nature-based Recreational Areas

Mt. Hood, Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forests, Waldo Lake, Odell Lake, Detroit and Hills Creek Reservoirs, Crater Lake National Park, Three Sisters, Sky Lakes, and Mount Jefferson Wilderness Areas, Willamette Hatchery

Elevation

98 feet (along the western border of the ecoregion) to 11,240 feet (Cascade peaks)

Important Rivers

Clackamas (Oak Grove Fork), McKenzie, Rogue, Umpqua, Breitenbush, Middle Santiam, North and Middle Fork of the Willamette

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor:

Altered Fire Regimes

CMP Direct Threats 7.1, 11.3, 11.4

Many forests in the West Cascades ecoregion are at risk of losing one or more ecosystem components to wildfire. Fire suppression and certain forest practices have resulted in young, dense, mixed-species stands of trees that are at increased risk of forest-destroying crown fires, disease, and damage by insects. Under changing climate conditions these risks are expected to increase, with warming temperatures and more frequent drought contributing to shorter fire return intervals and more severe fires. Efforts to reduce risks of uncharacteristically severe fires can help to restore habitat but require careful planning to provide sufficient habitat features that are important to wildlife (e.g., snags, downed logs, hiding cover).

Recommended Approach

Use an integrated approach to wildfire issues that considers historical conditions, wildlife conservation, natural fire intervals, and silvicultural techniques. Consider the broader landscape context, including habitat connectivity, cumulative impacts, fish and wildlife species presence, and mapped or modeled suitable habitat when engaging in forest management and wildfire risk mitigation activities. Reintroduce fire where feasible; prioritize sites and applications. Maintain important wildlife habitat features, such as snags and logs, to sustain wildlife species that are dependent on dead wood. Maintain early-, mid-, and late-seral habitats to support a diversity of species. Monitor these efforts and use adaptive management techniques to ensure efforts are meeting habitat restoration and wildfire prevention objectives with minimal impacts on wildlife. Work with homeowners and resort operators to reduce vulnerability of properties to wildfire while maintaining habitat quality. Highlight successful, environmentally sensitive fuel management programs. In the case of post-wildfire recovery, maintain high snag densities and replant with site-adapted native tree, shrub, grass, and forb species. Promote revegetation with native species that are expected to be climate resilient. Prevent colonization of invasive vegetation, such as scotch broom. Manage reforestation after wildfire to create species and structural diversity, based on local management goals.

Limiting Factor:

Water

CMP Direct Threats 7.2, 114

Water Quantity is a limiting factor for fish, wildlife, and livestock. Changing climate conditions are leading to rising temperatures and altered patterns of precipitation, which affect water availability across different times of year, and drought conditions are occurring more frequently. In high elevation areas, loss of snowpack due to warming climate conditions is affecting habitat for many species along the Cascade crest and is leading to reduced stream flow rates and peak flow rates that are occurring earlier in the year. In streams, seasonal low flows can limit habitat suitability, survival, and reproduction for many fish and wildlife species.

Water quality can also limit species and habitats. Runoff from agricultural areas and herbicides applied to forest lands can contaminate waterways. Warming temperatures, combined with higher nutrient levels due to agricultural runoff, are increasing the prevalence of toxic cyanobacterial blooms.

Recommended Approach

Provide incentives and information about water usage and sharing during low flow conditions (e.g., late summer). Promote water management actions that enable climate resilience and adaptation. Invest in watershed-scale projects for cold water and flow protection. Identify and protect cold water rearing and refugia habitat for aquatic species. Increase awareness and manage timing of applications of potential aquatic contaminants. Improve compliance with water quality standards and pesticide use labels administered by the DEQ and EPA. Work on implementing Senate Bill 1010 (Oregon Department of Agriculture) and DEQ Total Maximum Daily Load water quality plans.

Limiting Factor:

Habitat Fragmentation

CMP Direct Threats 1, 2.1, 2.3, 3.3, 8.1

Increasing traffic volumes, road density, recreational pressure, and urban and rural development are contributing to habitat loss and fragmentation, and create significant barriers to animal movements. Hydropower systems, including high-head flood control and hydropower dams, also have significant impacts to species movement in this ecoregion. Levees, hydropower canals, and hardened stream banks reduce available habitat for fish and aquatic species and can entrap and kill wildlife. Altered hydrology from these systems, including impacts to temperatures and timing of water availability, can affect fish passage.

Recommended Approach

Work with community leaders and local governments to encourage planned, efficient growth. Support existing land use regulations to preserve forestland, farmland, rangeland, open spaces, recreation areas, wildlife refuges, and natural habitats. Work with community leaders and agency partners to protect wildlife movement corridors and to fund and implement site-appropriate habitat enhancement and restoration efforts to facilitate wildlife movement. Continue working with Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, Oregon Department of Transportation, Oregon Department of Forestry, USFS, BLM, counties, local municipalities, irrigation districts, and other partners to inventory, prioritize, and provide fish passage at artificial obstructions, leveraging current work done by ODFW’s Fish Passage Task Force to expand implementation of fish passage priorities. Minimize entrapment risk in hydropower canals by providing crossing structures and escape devices at regular intervals. Provide incentives (e.g., financial assistance, conservation easements) and information about the benefits of maintaining wildlife habitat. Broad-scale conservation strategies will need to focus on restoring and maintaining more natural ecosystem processes and functions within areas that are managed primarily for other values. This may include an emphasis on more “conservation-friendly” management techniques for existing land uses, and restoration of some key ecosystem components such as riparian function.

Limiting Factor:

Invasive Species

CMP Direct Threat 8.1

Invasive plants and animals disrupt and degrade native communities, diminish populations of at-risk native species, and threaten the economic productivity of resource lands. Invasive plants, particularly noxious weeds, have increased substantially. In many cases, the spread of invasives is facilitated by wildfire, as many invasive species can quickly colonize disturbed areas. In this ecoregion, Scotch broom is of particular concern. Scotch broom spreads aggressively to form monocultures, displacing native, beneficial plants and forage grasses, with seeds that can remain viable for decades, making it very difficult to eradicate. Himalayan blackberry is also widespread, with significant local impacts to meadows, riparian areas, and grasslands.

While not as disruptive as invasive vegetation, invasive animals have caused problems for native wildlife species in this ecoregion. A variety of sport fish, introduced to many high elevation lakes, compete with native amphibians for limited resources and prey on native species and/or their eggs or young. Barred Owl, expanding westward from their native range in the eastern US, compete directly with the native, threatened Northern Spotted Owl for food and habitat.

Recommended Approach

Emphasize prevention, risk assessment, early detection, and quick control to prevent new invasive species from becoming fully established. Prioritize efforts to focus on key invasive species in high priority areas, particularly where Key Habitats and Species of Greatest Conservation Need occur. Where needed, use multiple site-appropriate tools (e.g., mechanical, chemical, and biological) to control the most damaging invasive species. During post-fire recovery efforts, use techniques that prevent establishment of or quickly eradicate invasive vegetation. Ensure native species are used during restoration and revegetation efforts and promote native species that are expected to be climate resilient.

Limiting Factor:

Recreational Activity

CMP Direct Threats 1.3, 4.1, 5.1, 5.2, 5.4, 6.1

Increasing demands for year-round recreational activity can disturb wildlife. Population growth has contributed to increased pressure on natural areas from recreationists, including those engaging in hiking, biking, camping, fishing, hunting, foraging, rafting, backcountry skiing, boating, paddleboarding, and off-road vehicle use. Expanded road and trail systems developed to help accommodate higher numbers of visitors are increasing habitat fragmentation and risks of behavioral impacts to wildlife. Recreational pressure can lead to an increase in wildlife stress response and behavioral changes that ultimately impact reproductive rates and population abundance. Human recreation can contribute to destruction of sensitive vegetation, harassment of wildlife from off-leash pets, spread of invasive species, and contamination of areas with refuse. Many species will avoid areas near trails, campgrounds, and access roads when humans are present.

Recommended Approach

Plan new recreational trail systems carefully and with consideration for native wildlife and their habitats. For example, limit use and access to certain areas to minimize disturbance to wildlife, avoiding areas more sensitive to damage such as wetlands. Take advantage of abandoned or closed roads, rail lines, or previously impacted areas for conversion into trails. Work with land management agencies such as the USFS to designate areas as high value recreation and low habitat impact areas. Institute road and/or area closures to protect species during sensitive times of year and decommission roads when possible. In high use areas, establish permitted entry systems to decrease recreational pressure. Engage in outreach and education to increase public awareness of recreation impacts to fish and wildlife species; develop messaging to communicate the need for “responsible recreation”.

Strategy Species

American Pika

Ochotona princeps

Beller’s Ground Beetle

Agonum belleri

Black Petaltail

Tanypteryx hageni

Black Swift

Cypseloides niger borealis

Bull Trout, Deschutes SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Hood SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Klamath Lake SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Odell Lake SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Bull Trout, Willamette SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

California Mountain Kingsnake

Lampropeltis zonata

California Myotis

Myotis californicus

Cascade Torrent Salamander

Rhyacotriton cascadae

Cascades Frog

Rana cascadae

Clouded Salamander

Aneides ferreus

Coastal Cutthroat Trout

Oncorhynchus clarki clarki

Coastal Tailed Frog

Ascaphus truei

Coho Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Coho Salmon, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Columbia Gorge Caddisfly

Neothremma andersoni

Columbia Gorge Hesperian

Vespericola depressa

Cope’s Giant Salamander

Dicamptodon copei

Fall Chinook Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Fisher

Pekania pennanti

Flammulated Owl

Psiloscops flammeolus

Foothill Yellow-legged Frog

Rana boylii

Franklin’s Bumble Bee

Bombus franklini

Fringed Myotis

Myotis thysanodes

Gray Wolf

Canis lupus

Great Basin Redband Trout, Upper Klamath Basin SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii

Great Gray Owl

Strix nebulosa

Great Spangled Fritillary

Speyeria cybele

Greater Sandhill Crane

Antigone canadensis tabida

Harlequin Duck

Histrionicus histrionicus

Hoary Bat

Lasiurus cinereus

Larch Mountain Salamander

Plethodon larselli

Leona’s Little Blue Butterfly

Philotiella leona

Lewis’s Woodpecker

Melanerpes lewis

Long-legged Myotis

Myotis volans

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

Northern Goshawk

Accipiter gentilis atricapillus

Northern Red-legged Frog

Rana aurora

Northern Spotted Owl

Strix occidentalis caurina

Northern Wormwood

Artemisia campestris var. wormskioldii

Northwestern Pond Turtle

Actinemys marmorata

Olive-sided Flycatcher

Contopus cooperi

Oregon Chub

Oregonichthys crameri

Oregon Shoulderband

Helminthoglypta hertleini

Oregon Slender Salamander

Batrachoseps wrighti

Oregon Spotted Frog

Rana pretiosa

Pacific Lamprey

Entosphenus tridentatus

Pacific Marten

Martes caurina

Purple Martin

Progne subis arboricola

Red Tree Vole

Arborimus longicaudus

Ringtail

Bassariscus astutus

Sierra Nevada Red Fox

Vulpes vulpes necator

Silver-haired Bat

Lasionycteris noctivagans

Spring Chinook Salmon, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Willamette SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Summer Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Summer Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Summer Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat

Corynorhinus townsendii

Umpqua Chub

Oregonichthys kalawatseti

Umpqua Mariposa Lily

Calochortus umpquaensis

Wayside Aster

Eucephalus vialis

Western Brook Lamprey

Lampetra richardsoni

Western Bumble Bee

Bombus occidentalis

Western Painted Turtle

Chrysemys picta bellii

Western River Lamprey

Lampetra ayresii

Western Toad

Anaxyrus boreas

White Rock Larkspur

Delphinium leucophaeum

White Sturgeon

Acipenser transmontanus

Winter Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Lower Columbia SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Winter Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Willamette SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Conservation Opportunity Areas

Antelope Creek-Paynes Cliffs [COA ID: 099]

This area includes important and rare low eleveation rocky outcropping and cliff habitat as well as Antelope Creek, historically one of the biggest producers of Summer Steelhead in the Rogue Watershed.

Big Butte Area [COA ID: 122]

This area is in the foothills of the West Cascades ecoregion and contains important Oak Woodland and Ceanothus Shrubland habitats.

Big Marsh Creek [COA ID: 133]

Area includes river headwaters near Crescent Lake Junction and flows into Oregon Cascades National Recreation Area.

Breitenbush River [COA ID: 110]

Area contains mid to high elevation managed forest and tributaries of the North Santiam River.

Bull of the Woods, North [COA ID: 108]

Areas is north of the Bull of the Woods Wilderness Area in the Mount Hood National Forest and contains the headwaters of the Clackamas River.

Bull Run-Sandy Rivers [COA ID: 105]

Area includes the headwaters of the Sandy River and its tributaries including the Bull Run River. Much of area is located within the Mt. Hood National Forest.

Calapooia River [COA ID: 082]

The Calapooia River Corridor spans from Albany through Tangent, Brownsville and through the Holley area.

Central Cascades Crest, Southeast [COA ID: 116]

Directly adjacent to the Upper Deschutes River COA.

Central Cascades Crest, West [COA ID: 113]

Partially bounded by the North Santiam River to the north, the McKenzie River to the west, and the Middle Fork Willamette to the south. Area encompasses significant high-quality fish and wildlife habitat next to wilderness areas managed for their conservation values

Clackamas River and Tributaries [COA ID: 065]

Area extends from the Willamette River area upstream to Estacada and includes floodplain, tributaries, and upland habitats.

Coburg Ridge [COA ID: 087]

Ridgeline, foothills, and associated lowlands bordering the east side of the ecoregion from Coburg Ridge to Indian Head

Crater Lake [COA ID: 121]

Crater Lake, Crater Lake National Park and surrounding wetlands and forest habitats.

Hood River [COA ID: 106]

Area includes Hood River mainstem, East and Middle Fork and numerous tributaries from confluence with Columbia River upstream. and

King Mountain Area [COA ID: 095]

This area contains federal lands intermixed with private ownership in a checkerboard matrix. Habitat is diverse inlcuding mature conifer forests, open early seral habitat created by logging, and oak woodlands. The area may serve as a possible movement corridor connecting the introduced southern Cascade Pacific Fisher population to the native Northern California/Southern Oregon population.

Little North Santiam River Area [COA ID: 109]

Area includes headwaters of North Santiam and Pudding Rivers, comprised largely of National Forest lands, private industrial forest and state-owned recreational areas.

Lower Sandy River [COA ID: 057]

This area is comprised of the 1,500-acre Sandy River Delta at the confluence of the Sandy and Columbia Rivers, plus the Lower Sandy River and its tributaries, including Beaver Creek and the lower reaches of the Bull Run River. Located east of the Portland Metro area in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area.

McKenzie River Area [COA ID: 114]

Area includes an important stretch of the McKenzie River, beginning just west of Willamette National Forest land and following the McKenzie through the city of Eugene

Metolius River Area [COA ID: 127]

Includes Metolius River basin, includes Green Ridge, and extends to include nearby valleys. Nationally known scenic recreation area that provides high quality habitat for fish and wildlife in Central Oregon.

Middle Fork Willamette River [COA ID: 115]

Follows a significant stretch of the Middle Fork Willamette River and its surrounding riparian and upland habitat, bounded to the west by the town of Dexter and extending east to the Oakridge Airport.

Middlefork Willamette River Headwaters [COA ID: 118]

Area includes a significant stretch of the Middle Fork Willamette River, from Hills Creek Reservoir to the north and extending east towards Summit Lake and the Diamond Peak Wilderness Area boundary

Missouri Ridge [COA ID: 070]

Area is located between Scotts Mills and Molalla in the Rock Creek subbasin, a tributary of the Pudding River.

Mt Hood Area [COA ID: 107]

Area is located within Mount Hood National Forest and includes the headwater streams of Hood, Clackamas, Sandy and White Rivers.

Mt Jefferson Wilderness, North [COA ID: 111]

Area is adjacent to Mount Jefferson Wilderness and includes headwaters of Clackamas, North Santiam and Deschutes Rivers.

North Umpqua River Area [COA ID: 090]

Near Roseburg, area includes a significant stretch of the North Umpqua River and its tributaries, and includes surrounding riparian and upland habitats

Odell Lake-Davis Lake [COA ID: 117]

Includes Davis Lake and surrounding habitat, continuing west to Salt Creek and encompassing the Crescent Lake Airport

One Horse Slough-Beaver Creek [COA ID: 083]

Area is located along the ecoregion boundary east of Albany adjacent to South Santiam River. The majority of the area is located in the One-horse slough quad

Pelican Butte-Sky Lakes Area [COA ID: 123]

At the ecoregion boundary adjacent to the East Cascades, and immediately adjacent to the Upper Klamath Lake COA in the East Cascades

Quartzville Creek Area [COA ID: 112]

Area includes Quartzville Creek, a major tributary of the Middle Santiam River, and is largely comprised of federally managed late-successional mixed conifer forest southwest of Mount Jefferson.

Rock Creek [COA ID: 120]

Relatively small (31 sq mi) COA encompassing an important stretch of Rock Creek. Area connects Umpqua Headwaters COA and North Umpqua COA, providing important fish and wildlife habitat connectivity.

Santiam Confluences [COA ID: 078]

The North Santiam River Corridor that borders Linn and Marion Counties from the confluence with the Willamette River through confluences of Jefferson ditch and Valentine Creek near Stayton and the South Santiam River ‘s Confluences with Spring Branch, Thomas Creek, Spring Creek, Crabtree Creek, Onehorse Slough, and Noble Creek to Sweet Home.

Shady Cove Foothills [COA ID: 098]

This area contains important Oregon and California Oak Woodlands and Ceanothus Shrublands. It is

Soda Mountain Area [COA ID: 124]

This area is a transition zone at the nexus of three ecoregions and as a results has a high diversity of species in unique assemblages.

South Fork Umpqua River and Tributaries [COA ID: 091]

Located in the middle of the ecoregion, this COA follows the windy course of the South Umpqua and many of its tributaries. Area boundaries near the towns of Roseburg, Winston, Dillard, Riddle, and Tiller

Umpqua Headwaters [COA ID: 119]

Located within the Umpqua National Forest and includes the headwaters of the Umpqua River.

Upper Deschutes River [COA ID: 129]

Follows the Upper Deschutes River closely from the Cascade Crest.

Upper Klamath Lake Area [COA ID: 138]

Includes Upper Klamath Lake, the largest freshwater lake west of the Rocky Mountains. Area includes surrounding habitat to the north and adjacent to the Sky Lakes area

Upper Siuslaw [COA ID: 089]

Follows the windy Siuslaw River and surrounding habitat. Area builds from the Siuslaw Estuary COA to the west and extends east towards Cottage Grove.

Upper Willamette River Floodplain [COA ID: 061]

This area includes the Willamette River floodplain from South of Springfield in the Dexter/Lowell area north to Albany.

Wasco Oaks [COA ID: 125]

Area extends from the Columbia River up through the Mt. Hood National Forest and has served as an important emphasis for conservation and restoration efforts.