Description

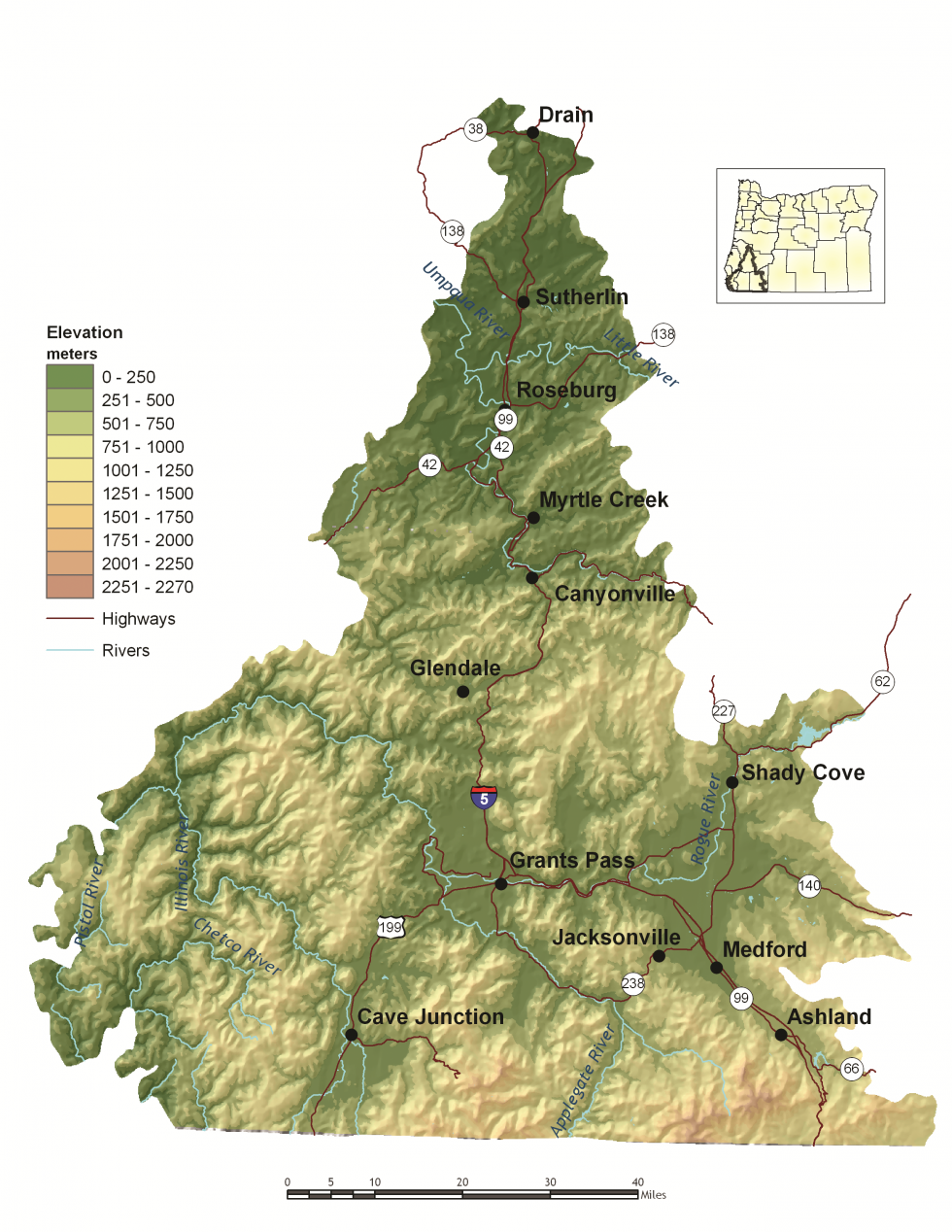

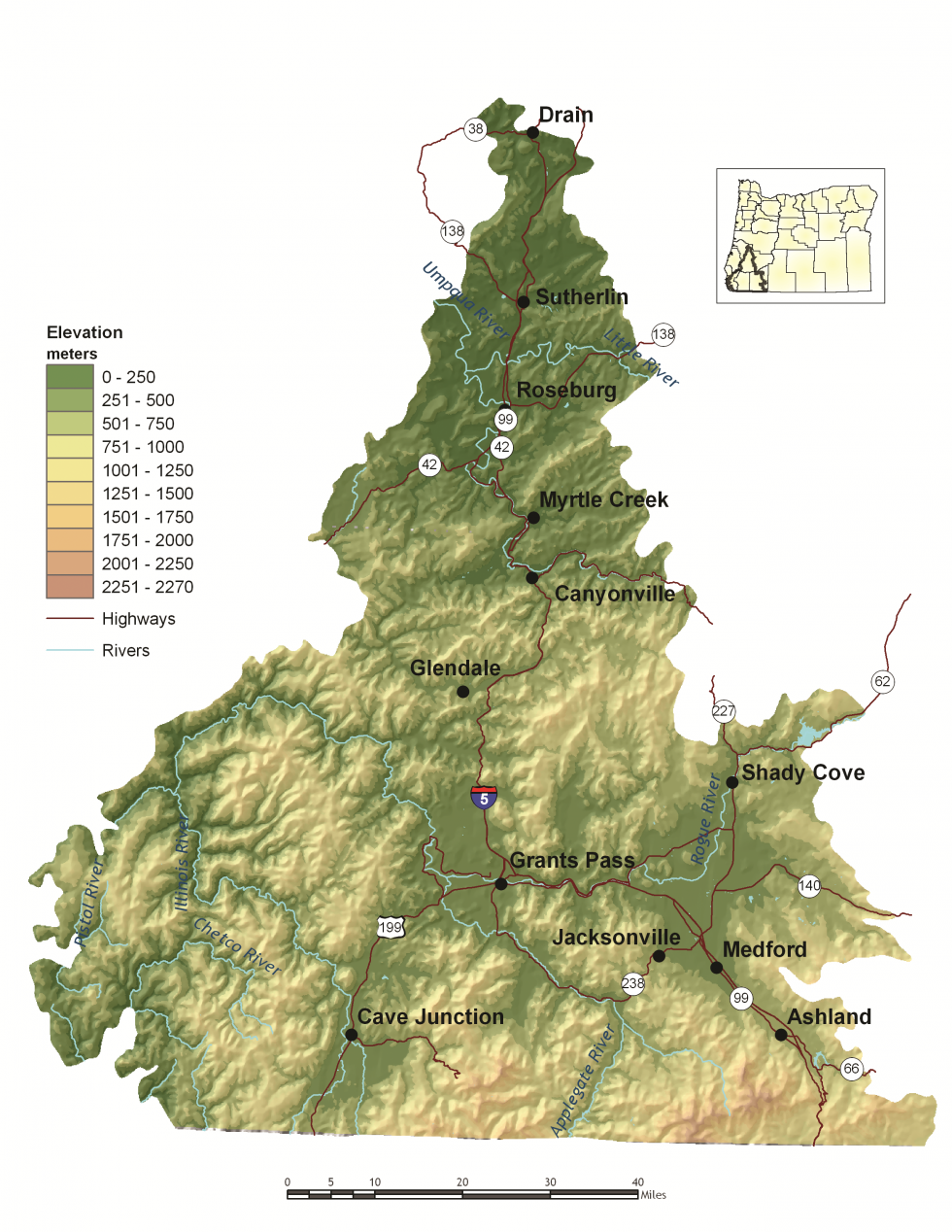

The Klamath Mountains ecoregion covers much of southwestern Oregon, including the Klamath Mountains, Siskiyou Mountains, the interior valleys and foothills between these and the Cascade Range, and the Rogue and Umpqua river valleys. Several popular and scenic rivers run through the ecoregion, including the Umpqua, Rogue, Illinois, and Applegate rivers. Historically, this ecoregion is known for some of the best anadromous fish habitat in Oregon. While the Klamath Mountains ecoregion has an abundance of rivers and streams, lakes and ponds are relatively rare and found almost exclusively in montane environments.

Within the ecoregion, there are wide ranges in elevation, topography, geology, and climate. The elevation ranges from about 60 to more than 7,500 feet, from steep mountains and canyons to gentle foothills and flat valley bottoms. This variation, along with the varied marine influence, supports a climate that ranges from the lush, rainy western portion of the ecoregion to the dry, warmer interior valleys and cold, snowy mountains.

Plate tectonics have played a major role in creating the complex mosaic of landforms and rock types in this ecoregion. The geology of the Klamath Mountains can be better described as a patchwork rather than the layer-cake geology of most of the rest of the state. In the Klamath Mountains, serpentine mineral bedrock has weathered to a soil rich in heavy metals, including chromium, nickel, and gold, and in other parts, mineral deposits have crystallized in fractures. In fact, mining was the first major resource use of the ecoregion following Euro-American settlement, and Jacksonville was Oregon’s most classic “gold rush” town.

Because of its unique geology, geography, and extreme climatic variation, the Klamath Mountains ecoregion boasts high species diversity, including many species found only locally. In fact, the Klamath-Siskiyou region was included in the World Wildlife Fund’s assessment of the 200 most important locations for species diversity worldwide. The region is particularly rich in plant species, including many pockets of endemic communities and some of the most diverse plant communities in the world. For example, there are more kinds of cone-bearing trees found in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion than anywhere else in North America. In all, of the 4,000 native plants in Oregon, more than half are found in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion. This biodiversity hotspot is species-rich for reptiles and amphibians, too, with 38 different native species calling the region home. The ecoregion also boasts many unique invertebrates, although many of these are not well studied. The complexity of topographies and microclimates have allowed the Klamath Mountains to act as a refuge from climate changes in the past, promoting species diversity, but land use changes and rapidly warming temperatures now threaten many of the region’s endemic species.

In June 2000, President Clinton established the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, which encompasses 86,774 acres of forest and grassland. This National Monument is the first U.S. National Monument set aside solely for the preservation of biodiversity. The United States Congress then expanded the protected area by designating the adjacent Soda Mountain Wilderness in 2009, which encompasses 24,100 acres. These protected lands are managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

While panning for gold first drew European settlers to the Klamath Mountains ecoregion, today’s communities have a wide range of industries and economies, including agriculture, timber production, healthcare, manufacturing, and tourism. Many retirement communities are rapidly growing in the Ashland and Grants Pass areas.

Characteristics

Important Industries

Forest products, service, tourism, trade, healthcare, new electronics, transportation equipment

Major Crops

Fruit (including wine grapes), vegetables, livestock, dairy farms, nursery products, timber, cannabis

Important Nature-based Recreational Areas

Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, Oregon Caves National Monument, Rogue-Siskiyou National Forest, Applegate Lake, Emigrant Lake, Howard Prairie Lake, Lost Creek Lake, Red Buttes and Kalmiopsis Wilderness Areas, Table Rock, North Bank Habitat Management Area, Denman Wildlife Area

Elevation

600 feet to 7,500 feet (Mt. Ashland)

Important Rivers

Applegate, Rogue, Chetco, Coquille, Umpqua, South Umpqua, North Umpqua, Illinois

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor:

Land Use Conversion and Urbanization

CMP Direct Threats 1, 2.1, 2.3, 7.2

Many communities in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion are expanding, particularly Central Point and Roseburg. Rapid urbanization can strain the ability of sensitive habitats, such as valleys, wetlands, and aquatic habitats, to continue to provide valued ecological functions and services. Development escalates the potential for conflict between people and wildlife. For example, more road traffic increases the likelihood of collisions with migrating species, creating hazards for both motorists and wildlife. Development in this area threatens the region’s unique geomorphic features and the diversity of plant and animal life they support.

Conversion of habitat for cannabis cultivation is also increasing in the Klamath Mountains. Cannabis cultivation can have disproportionately large impacts on the area under production. Cultivators often use substantial quantities of pesticides, including insecticides and rodenticides, to discourage wildlife from foraging on plants. In addition to killing pests, insecticides are toxic to native insect pollinators and other beneficial arthropods and decomposers. Anticoagulant rodenticides often result in poisoning or secondary poisoning of numerous non-target species. Additionally, cannabis is a water-intensive crop, and cultivation occurs during the dry season in the Klamath Mountains when water availability is already significantly decreased. Cultivation often requires stream diversions, which can alter habitat for fish and wildlife, change flow regimes, interfere with fish passage, and increase water temperatures.

Recommended Approach

Cooperative approaches with private landowners are the key to long-term conservation. Essential tools include financial incentives, conservation easements, and informational resources. Work with community leaders and local governments to ensure planned, efficient growth. Support and implement existing land use regulations to preserve farm and range land, open spaces, recreation areas, and natural habitats for wildlife. Support strategic land acquisition/protection, emphasizing species and habitats underrepresented in current protected sites. Ensure that local wildlife services are sufficiently maintained to help residents manage wildlife damage issues. Apply best management practices for cannabis cultivation to limit negative impacts to fish and wildlife and their habitats.

Limiting Factor:

Altered Fire Regimes

CMP Direct Threats 7.1, 8.2, 11.3, 11.4

Historically, the Klamath Mountains ecoregion was dominated by fire-adapted vegetation and experienced widely variable fire regimes, ranging from areas with relatively short fire return intervals to areas with greater than 50-year return intervals. Fire suppression and certain silvicultural practices have damaged forest health, resulting in undesirable changes in vegetation and increased intensity of wildfires as a result of increased fuel loads. Wildfire risk is further exacerbated by warming climate conditions and changes to patterns of precipitation, and more frequent, higher intensity megafires are becoming more common. Elevated levels of tree mortality due to drought, disease, and insects like fir borer, engraver, and mountain pine beetles have further increased fire risk in this ecoregion.

The cumulative impacts of these forest changes have drastically increased threats to biodiversity, not only from damage due to more frequent, higher-intensity wildfires, but also as a result of the loss of the frequent, mixed-severity fires needed to maintain structural diversity and a range of different species of vegetation in some forest types. Efforts to reduce fire danger can help to restore fish and wildlife habitat, but they require careful planning. Reintroducing fire can be challenging in the Klamath Mountains because of high volatility of fuels, “checkerboard” land ownership patterns, and scattered rural residential developments.

Recommended Approach

Use an integrated approach to fuels management and forest health issues that considers historical conditions, wildlife conservation, natural fire intervals, and silvicultural techniques. Encourage forest management at a broad scale to address limiting factors. Reintroduce fire where feasible. Prioritize sites and applications. Increase resources to help private landowners implement hazard reduction techniques. Maintain important wildlife habitat features, such as snags and logs, to sustain wood-dependent species. In areas where prescribed fire is undesirable or difficult to implement, use mechanical treatment methods (e.g., chipping, cutting for firewood) that minimize soil disturbance. Monitor efforts and use adaptive management techniques to ensure these practices are meeting habitat restoration and wildfire prevention objectives with minimal impacts on wildlife. Identify sub-basins with unique granitic sediment features that are especially at risk.

Limiting Factor:

Water

CMP Direct Threats 7.2, 11.4

Water Quantity is a limiting factor for fish and wildlife. In streams, seasonal low flows can limit habitat suitability and reproductive success for many fish and wildlife species. The Klamath Mountains ecoregion is highly susceptible to drought, with hot, dry summer climates. Changing climate regimes, such as predicted increased average summer temperatures and changes to patterns in precipitation, add to the likelihood and severity of drought conditions. Human activities, in the form of stream channelization, diversion systems, and irrigation operations, can also impact water availability, in addition to impacting in-stream and riparian habitat for fish and wildlife.

Water quality can also limit species and habitats. Runoff from agricultural areas can contaminate waterways. Warming temperatures, combined with higher nutrient levels due to agricultural runoff, are increasing the prevalence of toxic cyanobacterial blooms. Contaminants left from mining activities are also a concern for water quality. Seepage and leaching of contaminated sediments and groundwater can lead to the introduction of acidic mine drainage and other toxicants into waterways.

Recommended Approach

Provide incentives and information about water usage and sharing during low flow conditions (e.g., late summer). Promote water management actions that enable climate resilience and adaptation. Invest in watershed-scale projects for cold water and flow protection. Identify and protect cold water rearing and refugia habitat for aquatic species. Increase awareness and manage timing of applications of potential aquatic contaminants. Improve compliance with water quality standards and pesticide use labels administered by the DEQ and EPA. Work on implementing Senate Bill 1010 (Oregon Department of Agriculture) and DEQ Total Maximum Daily Load water quality plans. Follow guidelines outlined in regional species management plans, including the Rogue-South Coast Multi-Species Conservation and Management Plan

Limiting Factor:

Habitat Fragmentation

CMP Direct Threats 1, 2.1, 2.3, 3.3, 8.1

The Klamath Mountains ecoregion is naturally diverse and heterogeneous. Some habitat types have been particularly disrupted by fragmentation and loss of connectivity, including late-successional forests and valley bottom habitats. However, existing development, growth pressures, high land costs, disconnected land ownerships, and the fragmented nature of remaining native habitats all present barriers to large-scale ecosystem restoration.

Roadways are also a significant contributor to habitat fragmentation in this ecoregion. Interstate 5 bisects the ecoregion, running north to south. The number of lanes, traffic speeds, and volume of freight and motorist traffic make the interstate a near complete barrier to species movement, preventing species dispersal, range expansion, or migration. Undersized, inundated, and/or poorly maintained culverts and bridges also limit or prevent passage of fish and other aquatic species. Other roadways also impede wildlife connectivity and can block fish passage, particularly near urban areas. Densities of vehicle collisions with ungulates around the cities of Roseburg, Grants Pass, and Medford are some of the highest in the state.

Recommended Approach

Broad-scale conservation strategies will need to focus on restoring and maintaining more natural ecosystem processes and functions within a landscape that is managed primarily for other values. This may include an emphasis on conservation-oriented management techniques for existing land uses and restoration of some key ecosystem components, such as river-floodplain connections and riparian function.

Work with community leaders and agency partners to protect wildlife movement corridors and to fund and implement site-appropriate habitat enhancement and restoration efforts to facilitate wildlife movement. Promote the protection, restoration, and maintenance of Priority Wildlife Connectivity Areas, following the guidelines outlined in Oregon’s Wildlife Corridor Action Plan. Work with the Oregon Department of Transportation and county and city transportation departments to improve wildlife passage across roadways. Follow fish passage guidelines to prioritize and implement strategic removal of barriers to fish passage.

Limiting Factor:

Invasive Species

CMP Direct Threats 8.1, 8.2

Invasive plants are of particular concern in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion. Invasive plants disrupt native communities, diminish populations of at-risk native species, and threaten the economic productivity of resource lands. Scotch broom, cheatgrass, medusahead, and Himalayan blackberry are all prevalent and continue to spread. Non-native fish and wildlife species are also causing detrimental impacts. Feral horse populations have increased within the Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument, expanding beyond the Pokegama Herd Management Area. Unregulated horse herds have significant negative impacts, competing with native wildlife for vegetation and access to water, increasing soil erosion, and trampling sensitive habitats. American bullfrogs are rapidly expanding, competing with native species for limited resources or preying on native species and/or their eggs or young. Other problematic species include red-eared sliders, carp, signal crayfish, and mosquitofish.

Recommended Approach

Emphasize prevention, risk assessment, early detection, and quick control to prevent new invasive species from becoming fully established. Use multiple site-appropriate tools (e.g., mechanical, chemical, and biological) to control the most damaging invasive species. Prioritize efforts to focus on key invasive species in high priority areas, particularly where Key Habitats and Species of Greatest Conservation Need occur. Cooperate with partners through habitat programs and county weed boards to address invasive species problems. Promote the use of native species for restoration and revegetation.

Limiting Factor:

Energy Development

CMP Direct Threat 3.3

Climate change and global economies are increasing pressure for renewable energy development. Hydroelectric facilities currently cause the greatest impacts to fish and wildlife in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion. Hydroelectric energy production alters stream flow rates and timing in ways that are often at odds with fish and wildlife life cycles, breeding requirements, and other resource needs. Some facilities in the ecoregion have inadequate fish passage structures due to regulatory changes over the course of their permitted timeline. Wind and solar energy production are also increasing, with particular demand for new solar developments.

Recommended Approach

Plan energy projects carefully, using best available information and early consultation with biologists. See the Key Conservation Issue on Land Use Changes. Remove dams that are aging, inefficient, or obsolete, and use techniques like fish ladders, management strategies to reduce reservoir sedimentation, and seasonally appropriate flow release to help mitigate the negative environmental impacts of dams. Consider the broader landscape context when planning new facilities, including habitat connectivity, cumulative impacts, fish and wildlife species presence, and mapped or modeled suitable habitat. Use wildlife-permeable fencing or allow egress to permit passage for medium-sized animals through solar fields.

Limiting Factor:

Recreational Activity

CMP Direct Threats 1.3, 4.1, 5.1, 5.2, 5.4, 6.1

Increasing demands for year-round recreational activity can disturb wildlife. Activities like hiking, biking, hunting, fishing, jet boating, mushroom foraging, and off-road vehicle use can create sensory stressors for wildlife, with sound, light, and unusual smells that may deter species from moving through certain areas. Human recreation may contribute to destruction of sensitive vegetation, harassment of wildlife from off-leash pets, spread of invasive species, and contamination of areas with refuse. Many species will avoid areas near trails, waterways, campgrounds, and access roads when humans are present.

In the Klamath Mountains, extensive off-road vehicle use, both legal and illegal, increase stress for wildlife, and contributes to habitat fragmentation, disease transmission, and spread of invasive vegetation. Particular areas of concern for off-road vehicle impacts include the Applegate Valley, Shady Cove, and Illinois Valley.

Activities on waterways can also have detrimental impacts to fish and wildlife. Paddleboarding, increasing in popularity throughout the region, can affect birds and aquatic wildlife, with increased access to non-motorized waterways. Paddleboard use can also increase the risk of disease transmission without proper cleaning. Jet boat use is also popular in this ecoregion, with a number of commercial jet boat tours provided on the Rogue River. The timing, frequency, and extent of jet boat use in river habitats may create conflicts for anadromous and other fish, as well as wildlife.

Recommended Approach

Plan new recreational trail systems carefully and with consideration for native wildlife and their habitats. For example, limit timing and use of certain areas to minimize disturbance to wildlife, avoiding areas more sensitive to damage such as wetlands. Take advantage of abandoned or closed roads, rail lines, or previously impacted areas for conversion into trails. Work with land management agencies such as the USFS to designate areas as high value recreation and low habitat impact areas. Institute road and/or area closures to protect species during sensitive times of year and decommission roads when possible. Enforce laws surrounding illegal off-road vehicle use and consider seasonal closures during sensitive times of the year. Consider limiting access of both motorized and non-motorized watercraft to sensitive stream reaches. In high use recreational areas, establish permitted entry systems to decrease recreational pressure.

Strategy Species

Acorn Woodpecker

Melanerpes formicivorus

Big-flowered Wooly Meadowfoam

Limnanthes floccosa ssp. grandiflora

California Mountain Kingsnake

Lampropeltis zonata

California Myotis

Myotis californicus

Clouded Salamander

Aneides ferreus

Coastal Tailed Frog

Ascaphus truei

Coho Salmon, Klamath SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Coho Salmon, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus kisutch

Common Nighthawk

Chordeiles minor

Cook’s Desert Parsley

Lomatium cookii

Crinite Mariposa Lily

Calochortus coxii

Del Norte Salamander

Plethodon elongatus

Dwarf Meadowfoam

Limnanthes floccosa ssp. pumila

Eulachon

Thaleichthys pacificus

Fisher

Pekania pennanti

Flammulated Owl

Psiloscops flammeolus

Foothill Yellow-legged Frog

Rana boylii

Franklin’s Bumble Bee

Bombus franklini

Fringed Myotis

Myotis thysanodes

Gentner’s Fritillary

Fritillaria gentneri

Grasshopper Sparrow

Ammodramus savannarum perpallidus

Gray Wolf

Canis lupus

Great Gray Owl

Strix nebulosa

Green Sturgeon, Northern DPS

Acipenser medirostris

Green Sturgeon, Southern DPS

Acipenser medirostris

Hoary Bat

Lasiurus cinereus

Howell’s Mariposa Lily

Calochortus howellii

Howell’s Microseris

Microseris howellii

Kincaid’s Lupine

Lupinus oreganus

Large-flowered Rush Lily

Hastingsia bracteosa

Lewis’s Woodpecker

Melanerpes lewis

Long-legged Myotis

Myotis volans

Marbled Murrelet

Brachyramphus marmoratus

Mardon Skipper Butterfly

Polites mardon

McDonald’s Rockcress

Arabis macdonaldiana

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

Northern Red-legged Frog

Rana aurora

Northern Spotted Owl

Strix occidentalis caurina

Northwestern Pond Turtle

Actinemys marmorata

Oregon Shoulderband

Helminthoglypta hertleini

Oregon Vesper Sparrow

Pooecetes gramineus affinis

Pacific Lamprey

Entosphenus tridentatus

Pacific Marten

Martes caurina

Pallid Bat

Antrozous pallidus

Purple Martin

Progne subis arboricola

Red Tree Vole

Arborimus longicaudus

Ringtail

Bassariscus astutus

Rotund Lanx

Lanx subrotunda

Rough Popcornflower

Plagiobothrys hirtus

Sexton Mountain Mariposa Lily

Calochortus indecorus

Shiny-fruited Allocarya

Plagiobothrys lamprocarpus

Sierra Nevada Red Fox

Vulpes vulpes necator

Silver-haired Bat

Lasionycteris noctivagans

Siskiyou Hesperian

Vespericola sierranus

Siskiyou Mountains Salamander

Plethodon stormi

Southern Torrent Salamander

Rhyacotriton variegatus

Spotted Bat

Euderma maculatum

Spring Chinook Salmon, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Spring Chinook Salmon, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Summer Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Coastal SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Summer Steelhead / Coastal Rainbow Trout, Rogue SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss / Oncorhynchus mykiss irideus

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat

Corynorhinus townsendii

Umpqua Chub

Oregonichthys kalawatseti

Umpqua Mariposa Lily

Calochortus umpquaensis

Vernal Pool Fairy Shrimp

Branchinecta lynchi

Wayside Aster

Eucephalus vialis

Western Bumble Bee

Bombus occidentalis

Western Ridged Mussel

Gonidea angulata

Western Toad

Anaxyrus boreas

White-headed Woodpecker

Picoides albolarvatus

Yellow-breasted Chat

Icteria virens auricollis

Conservation Opportunity Areas

Anderson Butte [COA ID: 103]

This area is diverse with open south-facing meadows, oak woodlands, and mature conifers.

Antelope Creek-Paynes Cliffs [COA ID: 099]

This area includes important and rare low eleveation rocky outcropping and cliff habitat as well as Antelope Creek, historically one of the biggest producers of Summer Steelhead in the Rogue Watershed.

Big Butte Area [COA ID: 122]

This area is in the foothills of the West Cascades ecoregion and contains important Oak Woodland and Ceanothus Shrubland habitats.

Cape Ferrelo [COA ID: 051]

This area includes unique rocky intertidal habitat, important shorebird habitat, and coastal bluffs.

Chetco River-Winhchuck River Estuaries [COA ID: 052]

This diverse area includes habitats ranging from coastal dunes and estuaries to mature upland conifer forests.

East Fork Illinois River [COA ID: 101]

This area includes important riparian habitat in the East Fork Illinios River and Sucker Creek for Coho Salmon and Pacific Lamprey.

Grave Creek [COA ID: 094]

Area connects the Rogue River and King Mountain COAs, following Grave Creek and its surrounding habitat. Located just north of the town of Merlin

Illinois River-Silver Creek [COA ID: 096]

This large and diverse COA includes mature conifer forests as well as dense manzanita and Ceanothus brush fields created by the 2002 biscuit fire, which burned 500,000 acres in the Siskiyou National Forest. The COA contains serpentine soils that are home to the rare and endemic plant that make the Klamath Mountain Ecoregion an area …

Kalmiopsis Area [COA ID: 100]

This areas borders the western edge of the Kalmiopsis Wilderness and has unique plant communities due to the serpentine soils endemic to the Klamath Mountains ecoregion.

King Mountain Area [COA ID: 095]

This area contains federal lands intermixed with private ownership in a checkerboard matrix. Habitat is diverse inlcuding mature conifer forests, open early seral habitat created by logging, and oak woodlands. The area may serve as a possible movement corridor connecting the introduced southern Cascade Pacific Fisher population to the native Northern California/Southern Oregon population.

Lower Rogue River and Estuary [COA ID: 049]

This are contains the mouth of the Rogue River and is important habitat for Salmonids accessing the rest of the system. It has mature upland forests with a productive hardwood understory that supports a diverse assemblage of wildlife species.

North Medford Area [COA ID: 097]

This area includes important valley bottom habitat in the Rogue Watershed including the confluence of the Rogue River and Little Butte Creek, Upper and Lower Table Rock, and Vernal Pool habitat.

North Umpqua River Area [COA ID: 090]

Near Roseburg, area includes a significant stretch of the North Umpqua River and its tributaries, and includes surrounding riparian and upland habitats

Oregon Caves-Applegate Area [COA ID: 102]

This area north of the Red Buttes Wilderness and includes the Oregon Caves National Monument. Like much of the Klamath Mountains it is home to unique plant and wildlife species with limited ranges in Oregon, including native Pacific Fisher, Siskiyou Mountain Salamanders, and Brazilian Free-tailed Bats.

Pistol River Estuary [COA ID: 050]

This area contains the Pistol River Estuary, offshore rocky habitat for nesting seabirds, and Coastal Bluffs.

Rogue River [COA ID: 093]

This area contains habitat along the mainstem of the Rogue River including portions of the Wild and Scenic area.

Shady Cove Foothills [COA ID: 098]

This area contains important Oregon and California Oak Woodlands and Ceanothus Shrublands. It is

Siskiyou Crest Area [COA ID: 104]

This area is a long east-west running ridgline typical of the unique geology and ecology of the Klamath Mountains. It contains the head-waters for a number of stream, large mature conifers, and open alpine meadows.

Soda Mountain Area [COA ID: 124]

This area is a transition zone at the nexus of three ecoregions and as a results has a high diversity of species in unique assemblages.

South Fork Coquille [COA ID: 046]

Relatively large (222 sq mi) area located within the Coast Range near the Rogue River-Siskiyou Forest and immediately adjacent to the Sixes River-Elk River COA

South Fork Umpqua River and Tributaries [COA ID: 091]

Located in the middle of the ecoregion, this COA follows the windy course of the South Umpqua and many of its tributaries. Area boundaries near the towns of Roseburg, Winston, Dillard, Riddle, and Tiller

Tenmile Area [COA ID: 092]

Located west of hilly area near the town of Winston, following Highway 42

Umpqua Headwaters [COA ID: 119]

Located within the Umpqua National Forest and includes the headwaters of the Umpqua River.

Umpqua River [COA ID: 042]

Area follows the windy Umpqua River and surrounding riparian and upland habitat. Bounded at the north by Elkton and at the south near the towns of Melrose and Winchester

Upper Siuslaw [COA ID: 089]

Follows the windy Siuslaw River and surrounding habitat. Area builds from the Siuslaw Estuary COA to the west and extends east towards Cottage Grove.