Description

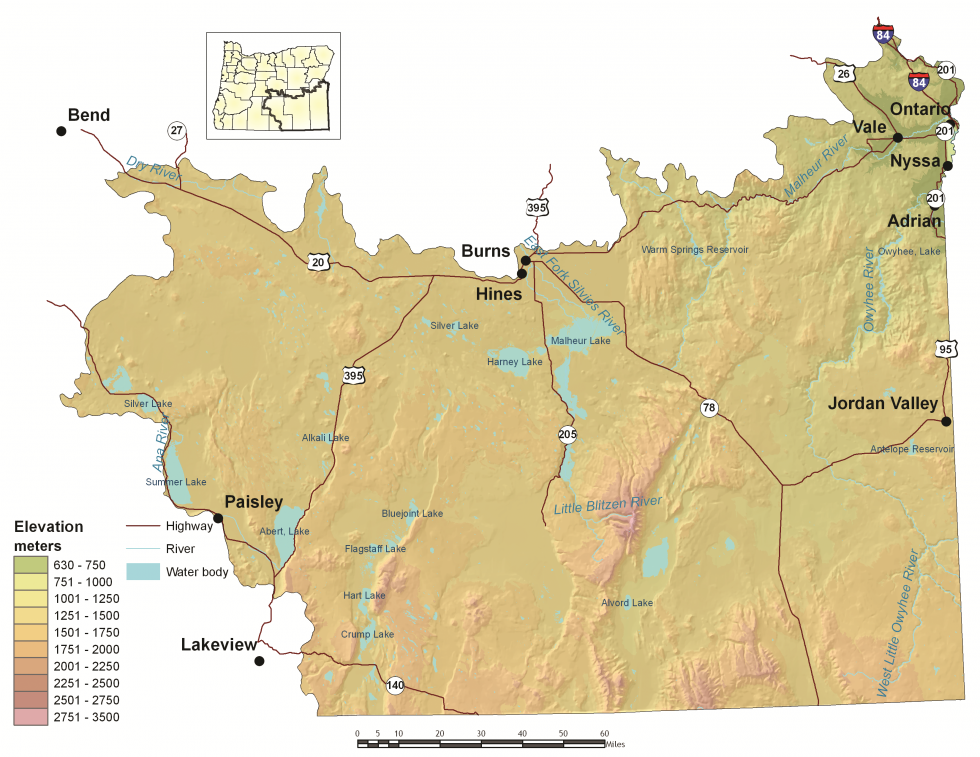

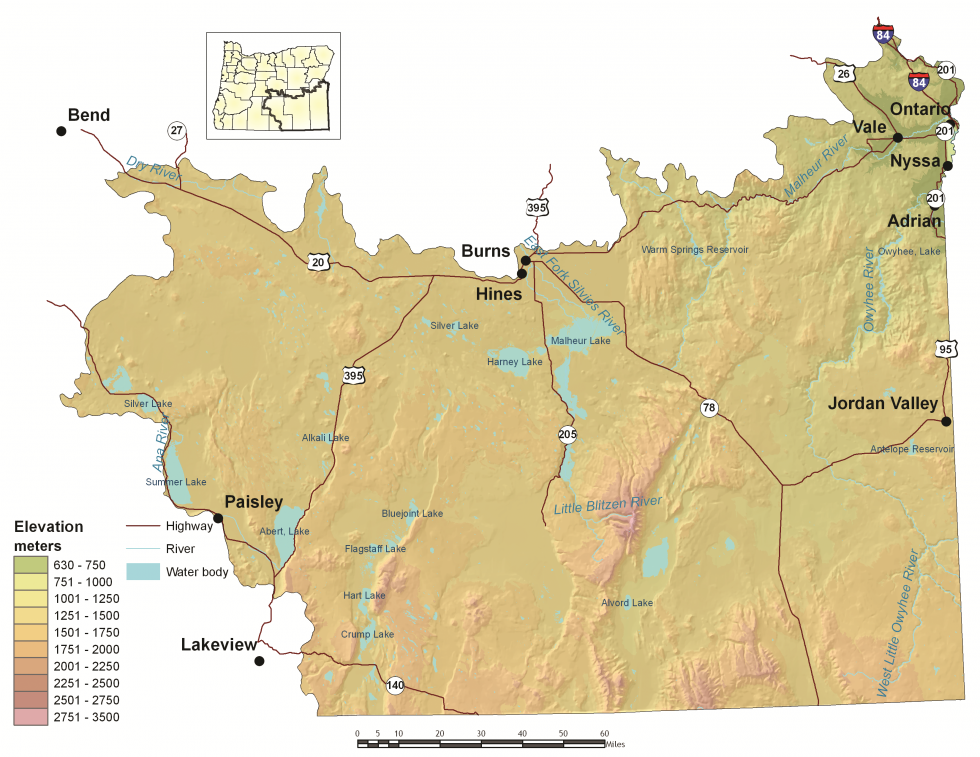

The Northern Basin and Range ecoregion covers the southeastern portion of the state, from Burns south to the Nevada border and from Fort Rock Valley east to Idaho. The name of this ecoregion describes the landscape, with numerous flat basins separated by isolated mountain ranges. This ecoregion encompasses several fault-block mountains, with gradual slopes on one side and steep basalt rims and cliffs

on the other side. The Owyhee Uplands consist of a broad plateau cut by deep river canyons. Elevations range from 2,070 feet near the Snake River to more than 9,700 feet on the Steens Mountain.

In the rain shadow of the Cascade Mountains, the Northern Basin and Range is Oregon’s driest ecoregion, marked by extreme ranges of daily and seasonal temperatures. Much of the ecoregion receives less than 15 inches of precipitation per year, although mountain peaks may receive 30-40 inches per year. The extreme southeastern corner of the state has desert-like conditions, with annual precipitation of only 8-12 inches. Despite regional aridity, natural springs and spring-fed wetlands are scattered around the landscape. Runoff from precipitation and mountain snowpack often flows into low, flat playas where it forms seasonal shallow lakes and marshes. Most of these basins contained large, deep lakes during the late Pleistocene, between 40,000 and 10,000 years ago. As these lakes, which don’t drain to the ocean, dried through evaporation, they left salt and mineral deposits that formed alkali flats, extremely important stopover sites for migratory shorebirds as a rich source of invertebrate prey.

Sagebrush communities dominate the landscape. Due to the limited availability of water, sagebrush is usually widely spaced and associated with an understory of forbs and perennial bunchgrasses, such as bluebunch wheatgrass and Idaho fescue. The isolated mountain ranges have few forests or woodlands, with rare white fir stands in Steens Mountain and Hart Mountain. However, aspen and mountain mahogany are more widespread and can be found in the Trout Creeks, Steens Mountain, Pueblo Mountains, Oregon Canyon Mountain, and Mahogany Mountains, and juniper woodlands comprise a significant portion of the northern end of the ecoregion. In the southern portion of the ecoregion, there are vast areas of desert shrubland, called salt-desert scrub, dominated by spiny, salt-tolerant shrubs. Throughout the ecoregion, soils are typically rocky and thin, low in organic matter, and high in minerals.

The Northern Basin and Range ecoregion is sparsely inhabited, but the local communities have vibrant cultural traditions. The largest community is Ontario, with more than 11,000 people. Other communities include Nyssa, Vale, Burns, and Lakeview, with 1,930 to 3,250 people each. Land ownership is mostly federal and primarily administered by the BLM. Livestock and agriculture are the foundations of the regional economy. Food processing is important in Malheur County. Recreation is a seasonal component of local economies, particularly in Harney County. Hunting contributes to local economies, as does wildlife viewing, white-water rafting, and camping. Historically, lumber processing and harvesting from the nearby Blue Mountains was the basis of some local communities, particularly for Burns. However, these industries have declined with lower harvests from neighboring federal forests.

Characteristics

Important Industries

Livestock, forest products, agriculture, food processing, recreation

Major Crops

Alfalfa, wheat, hay, corn, oats, onions, sugar beets, potatoes

Important Nature-based Recreational Areas

Summer Lake Wildlife Area, Malheur Lake National Wildlife Refuge, Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge, Steens Cooperative Management and Protection Area

Elevation

2,070 feet (Snake River) to 9,733 feet (Steens Mountain)

Important Rivers

Chewaucan, Donner und Blitzen, Malheur, Owyhee, Silvies

Limiting Factors and Recommended Approaches

Limiting Factor:

Altered Fire Regimes

CMP Direct Threats 7.1, 8.1, 8.2, 11.3, 11.4

Most sagebrush-dominated areas were once a mosaic of successional stages, from recently burned areas dominated by grasses and forbs to old, sagebrush-dominated stands that had not burned for 80 to 300 years. However, fire suppression and intensive grazing practices have reduced this mosaic and resulted in large areas dominated by invasive annual grasses, particularly cheatgrass, or older big sagebrush with a dense understory of invasive annual plants.

Changing climate conditions, including warming temperatures and more frequent and severe droughts, are contributing to increased frequency of fires, resulting in landscapes that are susceptible to the spread of western juniper and cheatgrass. Areas dominated by cheatgrass or other invasive annual grasses are more susceptible to fire ignition and reburning. Juniper invasion and encroachment of other woody vegetation provides fuel for wildfires, leading to higher intensity burns. Large fire events often destroy sagebrush, which are very slow to recover, leaving behind habitat that is no longer suitable for sagebrush-obligate species such as Greater Sage-grouse and pygmy rabbit. Big sagebrush communities with non-native invasive annuals in the understory will not recover from fire without significant intervention.

Recommended Approach

Under current vegetation management conditions, fire is damaging to sagebrush stands. Reintroduction of natural fire regimes may be difficult, and risks loss of sagebrush habitat. In many areas prescribed fire may be impractical. Use mechanical treatment methods that minimize soil disturbance to help remove encroaching juniper and annual invasive grasses that contribute to more frequent, higher-intensity fires. Chemical or biological management techniques can also be explored. In sagebrush habitats that are moderately impacted by invasive annual grasses, use of herbicides may help preserve sagebrush and increase fire resiliency. Engage in research on the efficacy and impacts of new herbicides to control nonnative vegetation.

Where appropriate, reintroduce natural fire regimes using site-appropriate prescriptions that limit risk of sagebrush loss, account for the historical fire regime, and encourage native plant regeneration. Use prescribed fire to create a patchy mosaic of successional stages and avoid large, prescribed fires.

Limiting Factor:

Water

CMP Direct Threats 7.2, 11.4

Water Quantity is a limiting factor for fish and wildlife. Changing climate conditions are leading to rising temperatures and altered patterns of precipitation, which affect water availability across different times of year. In streams, seasonal low flows can limit habitat suitability and reproductive success for many fish and wildlife species. Although many communities in this ecoregion are small, increases in the demand for water for crop irrigation and livestock production, coupled with increasing drought conditions, mean the supply of groundwater is decreasing. Already an arid ecoregion, increases in drought conditions have also resulted in the loss of some marshes and alkali lakes—areas that are critical for wildlife, particularly migrating birds. Water quality can also limit species and habitats. Warming waters provide conditions for increased bacterial growth which can impact fish and wildlife, as well as drinking water supplies.

Recommended Approach

Provide incentives and information about water usage and sharing during low flow conditions (e.g., late summer). Promote water management actions that enable climate resilience and adaptation. Invest in watershed-scale projects for cold water and flow protection. Increase awareness and manage timing of applications of potential aquatic contaminants. Improve compliance with water quality standards and pesticide use labels administered by the DEQ and EPA. Work on implementing Senate Bill 1010 (Oregon Department of Agriculture) and DEQ Total Maximum Daily Load water quality plans.

Limiting Factor:

Invasive Species

CMP Direct Threat 8.1, 8.2

Non-native annual grasses, particularly cheatgrass and medusahead, have rapidly expanded in the Northern Basin and Range, displacing desirable forage for wildlife and livestock. These invasive plants disrupt native communities, diminish populations of at-risk native species, and threaten the economic productivity of resource lands. The spread of invasives like cheatgrass and medusahead can also increase the frequency, intensity, and spread of fires, replacing sagebrush and native bunchgrasses, which are adapted to infrequent, patchy fires.

While not nearly as extensive as invasive plants, non-native animals have also impacted native fish and wildlife populations. For example, invasive carp in Malheur Lake have damaged one of the most important waterfowl production areas in Oregon, altering ecological dynamics through predation and altering water quality by disturbing sediments. Brown bullhead have also spread throughout the ecoregion, competing with native species for limited resources or preying on native species and/or their eggs or young. Unregulated horse herds are a concern in many areas, competing with native wildlife for vegetation and access to limited water sources, spreading invasive plant seeds via their manure, and trampling sensitive habitats.

Changing climate conditions and fire suppression have also led to the expansion of western juniper throughout the ecoregion. Western juniper is a native species, andold growth juniper trees in rocky outcrops offer benefits to native wildlife. However, the expansion of western juniper in the Northern Basin and Range has degraded some grassland, sagebrush, riparian, large-diameter juniper, and aspen habitats. Western juniper expansion may reduce water availability in many seasonal and some perennial streams. In riparian areas, junipers replace deciduous shrubs and trees that are more beneficial to riparian wildlife. In many of the grassland and sagebrush habitats, 20–30-year-old juniper trees form dense stands that are not suitable for many wildlife species that require the open sagebrush or grassland habitats that are now in decline. These dense stands also act as fuel for wildfire, contributing to large, high-intensity fires that destroy sagebrush habitat.

Recommended Approach

Controlling western juniper in newly invaded areas benefits wildlife and other habitat values. Early control of newly invaded young trees before woodlands become established is often the most successful approach. Develop markets for small juniper trees as a special forest product to reduce restoration costs. Maintain large-diameter juniper trees in the native rocky outcrops and ridges, which are important nesting habitat for passerines and raptors. In some areas, fire can be used to control young juniper. Carefully evaluate sites to determine if prescribed fire prescribed fire is appropriate, considering the landscape context, vegetation types, and risk of sagebrush loss.

Emphasize prevention, risk assessment, early detection, and quick control to prevent new invasive species invasive species from becoming fully established. Use multiple site-appropriate tools (e.g., mechanical, chemical, and biological) to control the most damaging invasive species. Prioritize efforts to focus on key invasive species in high priority areas, particularly where Key Habitats and Species of Greatest Conservation Need occur. Cooperate with partners through habitat programs and county weed boards to address invasive species problems. Carefully manage wildfires in cheatgrass-dominated areas. Promote the use of native “local” stock for restoration and revegetation where native species have the greatest potential to successfully establish. In some cases, use “assisted succession” strategies, applying low seed rates of non-invasive non-native plants in conjunction with native plant seeds as an intermediate step in rehabilitating disturbances in sagebrush communities.

Promote dialogue between wildlife managers, landowners, and land managers to develop horse management plans based on common priorities. Promote outreach to explain the issue to the public and the impacts of unregulated herds on wildlife and habitat.

Limiting Factor:

Energy Development

CMP Direct Threat 3.3

Climate change and global economies are increasing pressure for renewable energy development, including solar energy. Solar energy projects offer environmental benefits but also have significant impacts on wildlife and their habitat. Many solar energy facilities have large footprints. Federal requirements for facilities to be fully fenced make any remaining habitat within a solar field inaccessible to most terrestrial wildlife species, which results in lost habitat and may disrupt critical movement and migration pathways. Solar facilities are also a collision risk for birds, as reflection of sunlight off the panels may cause solar fields to resemble large water bodies. The area is increasingly challenged with the need to balance the state’s interest in clean energy development with local natural resource conservation needs. The Northern Basin and Range ecoregion offers excellent renewable energy resources, but the ecoregion is particularly sensitive to local impacts on sagebrush and other habitats.

Recommended Approach

Plan energy projects carefully, using the best available information and early consultation with biologists. Use available tools and resources found in the Land Use Changes and Climate Change KCIs and ODFW Compass. Consider the broader landscape context when planning new development, including habitat connectivity, cumulative impacts, fish and wildlife species presence, and mapped or modeled suitable habitat. Use wildlife-permeable fencing or allow egress to permit passage for medium-sized animals through solar fields.

Limiting Factor:

Recreational Activity

CMP Direct Threats 1.3, 4.1, 6.1

Increasing demands for recreational access can disturb animals and degrade habitats. Activities like hiking, biking, hunting, fishing, and foraging, and off-road vehicle use can create sensory stressors for wildlife, with sound, light, and unusual smells that may deter species from moving through certain areas. Human recreation may contribute to destruction of sensitive vegetation, harassment of wildlife from off-leash pets, spread of invasive species, and contamination of areas with refuse. Use of off-highway vehicles (OHVs) is particularly prevalent in the Northern Basin and Range. When limited and controlled, OHV use can be compatible with wildlife conservation. Illegal use, however, is prevalent, and highly detrimental. In general, OHV use can damage soils, impact sensitive riparian, aquatic, and upland habitats, spread invasive plant seeds, affect wildlife behavior and distribution, and increase the risk of wildfires. Although OHV use is limited to designated roads in some sensitive landscapes, there is little to no enforcement due to lack of funds and law enforcement personnel.

In addition to OHV use, other recreational use, such as camping, soaking in hot springs, rock climbing, and parasailing, is increasing. Use at some sites, such as the Alvord Desert, is high, and often damaging to sensitive desert playa habitat. Although recreational use is still light in comparison to more populated ecoregions, social media is driving increased use of several areas in the ecoregion. This increased recreational pressure could intensify impacts to wildlife and magnify disturbance in areas previously little-used by people.

Recommended Approach

Work cooperatively with land managers and OHV groups to direct use to maintained trails in low-impact areas and improve enforcement of existing rules. Support educational efforts to promote low-impact recreational use such as the Tread Lightly! Program. Monitor the impacts of OHV use on priority areas. Support efforts to effectively manage OHV use on public lands, particularly in highly sensitive habitats, and restore damaged areas.

Proactively consider potential impacts to wildlife and habitats when developing or promoting recreational opportunities to encourage compatible uses. Monitor recreational patterns and trends. Institute road and/or area closures to protect species during sensitive times of year and decommission roads when possible. In high use areas, establish permitted entry systems to decrease recreational pressure.

Limiting Factor:

Ongoing Recovery from Historical Overgrazing

CMP Direct Threats 2.3, 7.3, 8.1

Prior to limitations that were initiated on public lands in the mid-1930s, livestock grazing had a profound influence on landscapes throughout the Northern Basin and Range ecoregion. Many areas experienced serious ecological damage. Conditions on rangelands in general have improved substantially over the past half-century as a result of improvements in livestock management, and most ecosystems are recovering. However, some habitats have been slow to recover, such as some riparian areas areas and sagebrush communities, especially where cheatgrass and other invasive annual grasses have invaded.

Recommended Approach

Continue to proactively manage livestock grazing and restore degraded habitats. Minimize grazing during restoration of highly sensitive areas, such as wetlands and riparian areas.

Strategy Species

Alvord Chub

Siphateles alvordensis

American Pika

Ochotona princeps

American White Pelican

Pelecanus erythrorhynchos

Black-necked Stilt

Himantopus mexicanus

Bobolink

Dolichonyx oryzivorus

Boggs Lake Hedge Hyssop

Gratiola heterosepala

Borax Lake Chub

Siphateles boraxobius

Borax Lake Ramshorn

Planorbella oregonensis

Bull Trout, Malheur River SMU

Salvelinus confluentus

Burrowing Owl

Athene cunicularia hypugaea

California Myotis

Myotis californicus

Caspian Tern

Hydroprogne caspia

Columbia Clubtail

Gomphus lynnae

Columbia Spotted Frog

Rana luteiventris

Cronquist’s Stickseed

Hackelia cronquistii

Crosby’s Buckwheat

Eriogonum crosbyae

Davis’ Peppergrass

Lepidium davisii

Ferruginous Hawk

Buteo regalis

Foskett Spring Speckled Dace

Rhinichthys osculus robustus

Franklin’s Gull

Leucophaeus pipixcan

Fringed Myotis

Myotis thysanodes

Golden Buckwheat

Eriogonum chrysops

Gray Wolf

Canis lupus

Great Basin Redband Trout, Catlow Valley SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii

Great Basin Redband Trout, Chewaucan SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii

Great Basin Redband Trout, Fort Rock SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii

Great Basin Redband Trout, Malheur Lakes SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii

Great Basin Redband Trout, Warner Lakes SMU

Oncorhynchus mykiss newberrii/stonei

Greater Sage-Grouse

Centrocercus urophasianus

Greater Sandhill Crane

Antigone canadensis tabida

Grimy Ivesia

Ivesia rhypara var. rhypara

Hoary Bat

Lasiurus cinereus

Hutton Spring Tui Chub

Siphateles bicolor oregonensis

Juniper Titmouse

Baeolophus ridgwayi

Kit Fox

Vulpes macrotis

Lahontan Cutthroat Trout

Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi

Lahontan Cutthroat Trout, Coyote Lake SMU

Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi

Lahontan Cutthroat Trout, Quinn River SMU

Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi

Long-billed Curlew

Numenius americanus

Long-legged Myotis

Myotis volans

Malheur Cave Amphipod

Stygobromus hubbsi

Malheur Cave Flatworm

Kenkia rhynchida

Malheur Cave Springtail

Oncopodura mala

Malheur Isopod

Amerigoniscus malheurensis

Malheur Pseudoscorpion

Apochthonius malheuri

Malheur Valley Fiddleneck

Amsinckia carinata

Malheur Wire-lettuce

Stephanomeria malheurensis

Monarch Butterfly

Danaus plexippus

Mountain Quail

Oreortyx pictus

Mulford’s Milkvetch

Astragalus mulfordiae

Owyhee Clover

Trifolium owyheense

Packard’s Mentzelia

Mentzelia packardiae

Pallid Bat

Antrozous pallidus

Peregrine Falcon

Falco peregrinus anatum

Pit Sculpin

Cottus pitensis

Pygmy Rabbit

Brachylagus idahoensis

Silver-haired Bat

Lasionycteris noctivagans

Smooth Mentzelia

Mentzelia mollis

Snake River Goldenweed

Pyrrocoma radiata

Snowy Egret

Egretta thula

Spotted Bat

Euderma maculatum

Spring Chinook Salmon, Upper Snake SMU

Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Sterile Milkvetch

Astragalus cusickii var. sterilis

Swainson’s Hawk

Buteo swainsoni

Townsend’s Big-eared Bat

Corynorhinus townsendii

Trumpeter Swan

Cygnus buccinator

Warner Sucker

Catostomus warnerensis

Western Bumble Bee

Bombus occidentalis

Western Snowy Plover

Charadrius nivosus nivosus

Western Toad

Anaxyrus boreas

White-tailed Jackrabbit

Lepus townsendii

Willow Flycatcher

Empidonax traillii

Conservation Opportunity Areas

Alkali Lake [COA ID: 190]

Encompassing Alkali Lake, this COA is the smallest in the Northern Basin and Range ecoregion. It is located north of Lake Abert and just west of US Highway 395 in eastern Lake County.

Alvord Lake Basin [COA ID: 194]

The northern extent of this long narrow COA includes Tudor Lake at the eastern base of Steens Mountain. Continuing south and encompassing a large swath of the Alvord Desert, including the seasonal and alkali Alvord Lake, the COA ends just south of the community of Fields in the Pueblo Valley.

Basque Hills Area Plains [COA ID: 202]

Barely crossing into Lake County on its western edge, This COA is predominantly located in southwestern Harney County and connects to the Sage Hen Creek COA (201) and the Hart Mountain Area COA (200) on its western and southeastern borders. It encompasses an area from Mahogany Mountain in the north to the southern edge of …

Brothers-North Wagontire [COA ID: 184]

The northern extent of this COA includes the Bear Creek Buttes and Rodman Rim area in the Ochoco Mountain foothills. South of US Highway 20, the COA encompasses Pine Mountain and a large area of sagebrush steppe dotted by numerous buttes north of Christmas Valley. Heading east it covers Elk Mountain and Rams Butte before …

Bully Creek Area [COA ID: 183]

Adjacent to North Fork Malheur – Monument Rock area, including significant stretches of Clover Creek and Bully Creek

Chewaucan River [COA ID: 141]

Area includes the Chewaucan River and surrounding habitats

Crowley [COA ID: 185]

This rugged COA begins in Harney County near the confluence of Crane Creek and the South Fork Malheur River. Moving north east, the COA crosses into Malheur County and wraps around Swamp Creek Buttes. Continuing north towards Juntura, it then follows an eastward line (south of US Highway 20) towards Namorf. Finally, the COA heads …

Foster Flat-Black Rim Sagebrush Area [COA ID: 191]

Located in the Foster Flat area, south of Harney Lake and west of US Highway 205, this COA encompasses large areas of sagebrush steppe shrublands and scattered wetlands.

Harney-Malheur Area [COA ID: 187]

This COA encompasses both Harney and Malheur Lakes at the north end and then heads south along the Donner and Blitzen River and Blitzen Valley. An eastern finger of the COA continues out of the valley as far as the town of Diamond and the southern finger ends near French Glen.

Hart Mountain Area [COA ID: 200]

Mainly located in south eastern Lake County, this COA encompasses an area from the Oregon/Nevada border in the south; Coleman Valley and Warner Valley in the west; Guano Valley and Mahogany Butte in the east, and across to the southeastern corner of Hart Mountain National Antelope Refuge in the north. The COA includes several protected …

Jordan Creek Wetlands [COA ID: 195]

Located in east-central Malheur County, this small COA encompasses Jorden Valley and the surrounding hills, from the Oregon/Idaho border west into Jordan Creek Canyon.

Lake Abert [COA ID: 197]

Located in central Lake County, this COA encompasses Lake Abert, including the Lake Abert Area of Critical Environmental Concern and portions of the Abert Rim Wilderness Study Area.

Little Louse Canyon [COA ID: 205]

Located in Southeastern Malheur County, this western extent of this COA includes High Peak and Battle Mountain; the eastern edge is found close to Louse Creek; its northern extent is approximately five miles north of Big Antelope Creek – before its confluence with the Owyhee River; and the southern border includes the upper reaches of Big Antelope …

Long Creek-Coyote Creek-Silver Creek [COA ID: 135]

Area comprised of three major sub-watersheds immediately adjacent to Sycan Marsh, including river confluence.

Malheur River Headwaters [COA ID: 180]

The Malheur River Headwaters COA spans two ecoregions. Within the BM ecoregion, the COA includes Logan Valley and part of the Strawberry Mountain Wilderness and continues south to Battle Mountain (just north of Highway 306). Within the NBR, the COA is comprised of land associated with the Malheur River south of Battle Mountain to approximately …

Middle Owyhee River Area [COA ID: 186]

This COA is located in the northeast quarter of Malheur County and abuts the Crowley COA to the west. It encompasses Owyhee Lake and River from just east of Mitchell Butte (near the city of Adrian) south to Greeley Bar. Continuing south and east, the COA includes the rugged landscape of Mahogany Mountain, Jordan Craters, …

Pueblo Mountain [COA ID: 203]

This COA encompasses the southern Oregon Pueblo Mountains from Cottonwood Creek in the north to the Monument Basin in the southwest and then east across the Pueblo Valley towards the foothills of the Trout Creek Mountains. It includes the Pueblo Mountain Wilderness Study Area; the Tum Tum Lake Research Natural Area, and the Pueblo Hills …

Quartz Mountain [COA ID: 131]

Includes significant wetland and wet meadow areas. Immediately adjacent to NB COA “Brothers – North Wagontire”.

Rattlesnake Creek-Calamity Creek Area [COA ID: 181]

At the border of Grant and Harney County, area encompasses important sections of Rattlesnake Creek and Calamity Creek, immediately adjacent to the Silvies River COA

Sage Hen Creek [COA ID: 201]

Located in the southeast corner of Lake County and the southwest corner of Harney County, this COA encompasses the southern and eastern portion of Guano Valley and continues east from Guano Rim to the foothills of Bald Mountain and Acty Mountain. It includes the Spaulding and Hawk Mountain Wilderness Study Areas and the Hawksie-Walksie Research …

Silver Creek Area [COA ID: 175]

Located at the southern edge of the Blue Mountains Ecoregion, just west of the Silvies River. Area includes ecologically significant stretch of Silver Creek and its surrounding habitat

Soldier Creek-Upper Owyhee River [COA ID: 196]

The eastern edge of this COA follows the Oregon/Idaho border from the Jordan Valley area south to the North Fork Owyhee River. It then moves west and north into the Owyhee Canyon, and includes the Spring Creek watershed and the Oregon portion of the Soldier Creek watershed. Finally, the COA covers most of Antelope Reservoir …

South Fork Crooked River Area [COA ID: 174]

At the southern edge of the ecoregion, adjacent to several COAs and slightly west of the town of Burns

Steens Mountain [COA ID: 192]

This COA includes much of Steens Mountain’s southwestern flank before moving north and skirting along the edge of Malheur National Wildlife Refuge and then east into the northern Steens Mountain uplands and High Lava Plains.

Summer Lake Area [COA ID: 189]

This area is comprised of Summer Lake and the surrounding high desert wetlands subregion, including much of the Diablo Mountain Wilderness Study Area.

Ten Cent Lake-Juniper Lake Area [COA ID: 193]

This COA encompasses an area south of US Highway 78 that spans Malheur and Harney Counties from the Sheepshead mountains in the east to Burnt Flat and Comegys Lake on the northern flank of Steens Mountain.

Three Forks [COA ID: 206]

This is the most southeastern COA in Oregon and shares borders with Idaho and Nevada. It includes significant sections of the main stem Owyhee River, the Middle Fork Owyhee River, Little Owyhee River, and Toppin Creek. Its northern extent includes the three forks confluence, and its western border abuts the Little Louse Canyon COA (205) …

Trout Creek Mountains [COA ID: 204]

Spanning an area in the southeastern corner Harney County and southwestern Malheur County, this COA encompasses the Trout Creek Mountains, the Oregon Canyon Mountains, and the Blue Mountains. It includes numerous Wilderness Study Areas, such as Disaster Peak, Alvord Desert, Fifteenmile Creek, Mahogany Ridge, Oregon Canyon, Twelvemile Creek, and Willow Creek.

Upper Silvies River [COA ID: 178]

Includes significant stretch of the Silvies River and surrounding habitat. Spans Blue Mountains (bounded at the north by the town of Seneca) and Northern Basin & Range Ecoregion (starting at Malheur Lake to the south), passing through the town of Burns

Upper South Fork Malheur Area [COA ID: 188]

This COA straddles US Highway 78 southeast of Malheur Lake and provides connectivity between the Crowley (185) COA, Ten Cent Lake-Juniper Lake Area (193) COA, and the Steens Mountain High Lava Plains (192) COA. North of US Highway 78 the COA includes Malheur Cave and a section of South Fork Malheur River. South of 78 …

Warner Basin Wetlands [COA ID: 199]

Encompassing Warner Valley and associated wetlands, this COA stretches from just above Blue Joint Lake in the north to the Oregon/Nevada border in the south, and includes the Rahilly-Gravelly Research Natural Area, the Fish Creek Rim Research Natural Area, and the Warner Wetlands Area Of Critical Environmental Concern.

Warner Mountains [COA ID: 146]

Area located east of Lakeview along the eastern border of the ecoregion

Warner West [COA ID: 198]

This COA includes portion of Abert Rim Wilderness Study Area, Fish Creek Rim Wilderness Study Area, Lake Abert Area of Critical Environmental Concern, and the Fish Creek Rim Research Natural Area. It encompasses an area between Abert Rim and the Warner Mountains on the western edge to South Warner Rim and Lynches Rim to the …

Willow Creek-Birch Creek Area [COA ID: 167]

Located between the towns of Brogan and Huntington, at the eastern border of the ecoregion adjacent to the Snake River